The campaign group Living Streets (originally founded as the Pedestrians’ Association in the 1930s) published two detailed reports on bus stops by cycleways, and continuous footpaths.

Above – what does your neighbourhood doughnut look like?

For those of you like me who like the to read the printed versions you can print them out but they will drink ink. There’s a thought for a community interest company: set up a small printing establishment that can print out on request such documents to save people (me) from doing so at home, with a simple ‘print-on-demand’ facility where you plug in the web address of the report you want, you get a quotation back based on the number of pages and quality/colour you want, pay online and it arrives a few days later.

In the near future we’re all going to have to respond and adapt to the climate emergency

Hence asking about learning the practical skills needed back in summer 2022

- A knowledgeable population able to ask the right questions and able to learn what changes they will need to make to their homes and lifestyles

- A willingness of that population – or at least a critical mass of them/us to make those changes – which also involves political legitimacy

- A skilled workforce to do the practical work – even if it involves a fair amount of DIY or co-working with installers

- Experts to train the trainers – and trainers to up-skill the workforce and residents

- Suitable, affordable, and accessible venues where at least some of the practical training can take place

- Someone to co-ordinate this work and keep the city informed – learning the lessons from the Greater Cambridge Partnership

- Funding

- Enthusiastic co-operation from property owners and businesses

- Enthusiastic co-operation from public sector organisations – even though it feels like continual fire-fighting for them

- A culture of collective learning ( – and accepting that we’re all starting from different points), doing, evaluating, and improving across our city so no one is left out.)

Above – from July 2022. Progress update?

What we’re starting to see some of the long-discussed design principles being applied to actual neighbourhoods

Take the Cambridge Northern Design Code covering Arbury, King’s Hedges, and parts of Chesterton

Above – NCDC 2024 p33 – What could a revamped civic centre in Arbury be like in 30 years time?

One of the things to emphasise is the long-term time scales – it won’t mean people being thrown out of their homes en masse. But it will have to mean a well-managed transition over time. Easier said than done as some of the residents of Ekin Road can tell you.

Then there are specific repeated cases such as bus stops along proposed cycleways

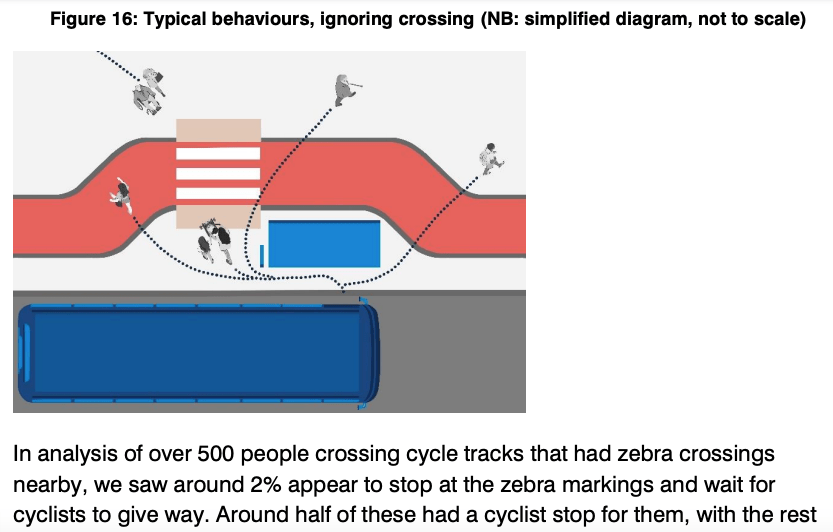

Above – Inclusive design at bus stops with cycle tracks, Living Streets p22

Chances are you can pick out issues and flaws in each of the examples given above. With the first design, the guide looks at desire lines for both pedestrians and cyclists.

Above – Inclusive design at bus stops with cycle tracks, Living Streets p76

The guide also discusses when cyclists choose to ignore the cycle lanes and stick to the roads – especially the faster, physically fitter, and perhaps more confident cyclists, who may simply see the zebra crossing as an unwanted delay or interruption on their journey. (Note some of the offences that can be committed by cyclists)

My interest is in how councils can use excellent urban design principles to ‘design out’ conflicts between the different modes of transport so as to reduce the likelihood of accidents and injuries so that the only people who end up before the courts are the ones who have chosen to break the law. That also requires other policy initiatives including educating the public about transport law – and thus the rule of law and local democracy in general. Hence civics and citizenship education.

Above – an example of profits being put before public safety in urban design

Many of us are familiar with how bus stop seating feels designed ot be as uncomfortable as possible – perhaps for reasons such as reducing anti-social behaviour by making such places uncomfortable for people to gather. But that reflects dealing with a symptom rather than an underlying causes – for example lack of provision of youth services for young people through to poor healthcare provision and poor housing provision for people who are homeless. This is an example of the complexity of public policy as a concept – actions have so many knock-on impacts. Cutting the budget for youth services may provide a benefit in one cell in a spreadsheet, but has a knock-on impact in someone else’s spreadsheet and across wider communities that existing models cannot account for.

How do we make these issues part of general election conversations?

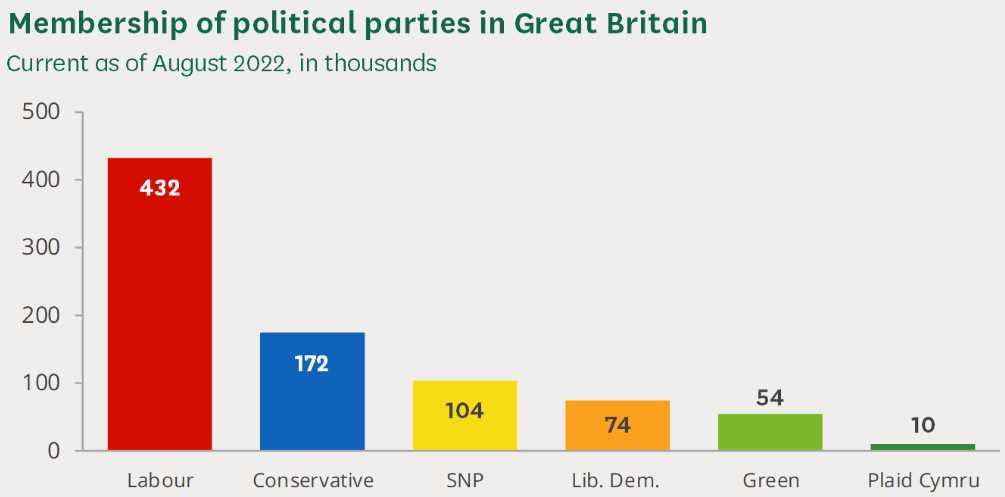

Assuming that the Prime Minister doesn’t call an election for June/July 2024, there are a host of summer community events where campaign groups can book stalls and/or put up exhibitions for people to look at passively and not be given a ‘hard sell’. Again, easier said than done when it comes to engaging with the public (as I found out the hard way last month). It’s worth remembering that being an activist in campaigner for anything is not normal. Look at the figures for party political membership from August 2022:

Above – House of Commons Library – Membership of Political Parties (2022)

Yet according to one survey, 20% of people are paying members of charities. One of the largest of those is The RSPB – the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, with 1.2million members. (More than the membership of all the political parties in Great Britain put together).

This in part explains why as individuals and collectively we cannot leave things to the politicians and political parties. How we turn ideas into actions again is easier said than done. Part of the solution in my view is educating and informing the public about how our systems of governance function and malfunction – as I wrote here. Getting to that point however is going to require a push from civic society organisations as much as anyone. But given where we are with all things politics and government, I wouldn’t blame anyone from simply turning away. Especially in an age where people seem to have so little free time in the face of competing demands. (Just ask any parent or carer).

Food for thought?

If you are interested in the longer term future of Cambridge, and on what happens at the local democracy meetings where decisions are made, feel free to:

- Follow me on Twitter

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge.

Below: Some questions from Frank Hardie in 1945 that are still relevant to today