Some interesting lessons learnt at the Academy of Urbanism’s congress – and not perhaps the ones I thought after day 1. (For those of you wondering who the town owl is inspired by, look at the clock at the top of the Guildhall overlooking Market Square in Cambridge).

I’m a sort of partial attendee, unable to take part in the excursion part of the events because CFS/ME means I have to spend the afternoon crashed out recharging batteries. This was also my first corporate event in many years – certainly my first since the lockdowns. As a result I’ve noticed how different I am compared to what feels like a previous era of being a social butterfly at such events. My health no longer allows for. that- for better or worse!

So I can’t really comment on who said what in the tours of the various sites. That said, the comments in the opening speeches – in particular from the Pro Vice-Chancellor Prof Andy Neely of the University of Cambridge caused a little disquiet (to put it mildly) with the picture he painted of the institution he represented, and its relationship with the local councils and ‘town’.

Part of me was tempted to heckle:

“Well I didn’t vote for you!”

But then we might have had a localised version of the Monty Python politically-aware peasant scene created by those former local residents who went onto greater things.

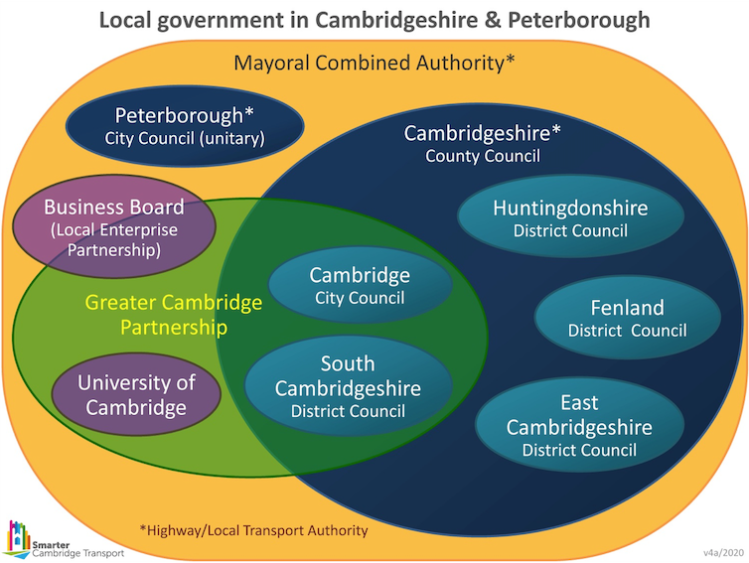

I hope either a video or a transcript of Prof Neely’s speech is published because I believe there is a strong local public interest for a wider audience to read/hear what he said – and scrutinise it. Even more so given he is the University of Cambridge’s representative on the Greater Cambridge Partnership Board, and is the vice-chair of the Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Combined Authority’s Business Board. Therefore what he says in meetings has a wider influence across not just our city, but our county too.

I put a question to Prof Neely on why his university had de-prioritised a major leisure infrastructure project (the proposed large swimming pool for the University’s sports centre) despite its huge wealth and income. I also reminded him of the commitment Sir Ivor Jennings, a former Vice-Chancellor made in 1962 about the University’s responsibility for our city. He responded that the University just about breaks even (in response to my financial point). Which as some have said is not the same as the wealth of individual colleges. But then this is where we come to the controversial point. Who gets to decide when the University of Cambridge can say ‘…and all the colleges’ vs ‘oh the colleges are separate’?

Because when it comes to raising money from former students, the University of Cambridge is more than happy to publicise the total figure of fundraising

Above – from the University of Cambridge’s philanthropy pages

“Well the University and the Colleges have separate royal charters, and a chap like you should know that!”

This isn’t about me – this is about the people who make up our city. Residents, commuters in, regular visitors, students, children, retired people and so on being able to scrutinise those in and with power.

To most people, there is no difference between “The University of Cambridge” and the individual component colleges. Understandably, Prof Neely mentioned that the structures of the institutions and their relationships are complex. Given that one of its former students Daniel Zeichner MP (Labour – Cambridge) told me that after several years of being our city’s MP he still had not identified where the real centres of power really were in the institution, can anyone really say that it is democratic if power cannot be held accountable?

Furthermore, if the University and its colleges were genuinely democratic, would campaign groups such as the Cambridge Land Justice Campaign exist, let alone provide platforms for successive generations of students to call out the lack of transparency and accountability of the institutions that they are members of?

It’s not just the University of Cambridge that has this issue. Two others I can think of:

“Potholes are a county council issue, not a city council issue”

Tell that to any local election candidates standing for district/borough level council elections in two tier areas (such as Cambridge) and they’ll say that this makes no difference to their local electorate. They see ‘the council’ as one and the same – and there are vastly more people of that viewpoint than those who understand the nuances of the local government structures that date back to 1974.

“That’s an issue for Parliament, not the Government”

The Foreign Secretary Mr Cleverley tried that trick on telly. regarding the former PM’s censuring by the House of Commons. It didn’t work.

Above: Ministers of the Crown have to be a member of either house – about 90% of them members of the House of Commons. Journalist Sarah-Jane Mee quite rightly reminded the Foreign Secretary that as an MP his constituents had a right to expect him to vote on such an important issue. During the MPs’ expenses scandal before the 2010 general election, ministers appearing on BBC Question Time tried the same when saying that reforming the system was a matter for Parliament – even though said ministers were also MPs.

Either the structures and systems of those institutions need to be consolidated, simplified and rationalised so that it’s easier for the public to hold power to account, or representatives from those institutions need to deal with the substantive difficult questions rather than conveniently hiding behind the opaque and over-complicated structures in order to dodge the issue.

What I’m getting at here is the institutions, not the individuals. It could have been any other Minister of the Crown, or any other representative of the University of Cambridge. Chances are the results would have been the same. These just happened to be the two individuals that caught my attention on and off screen today.

In each of those cases, how does anyone go about holding “The colleges” or “The Council” or “Parliament” to account when representatives from those institutions reply that the difficult issue is for ‘someone who is not them’ to answer for – but one that is not easy for the public to ‘pin down’? And let’s face it, all three sectors – ‘Westminster’, local government, and higher education are all in crisis mode at the moment for a variety of reasons – some the same (eg decisions by ministers to cut funding), some different.

The wider issue closer to home is about how the City of Cambridge has become a brand not in the control of the city council, and is used by a whole host of industries ‘to extract financial value’ from it. Whether the language schools or private colleges that have their brochures filled with picture-postcard views of the ancient colleges even though their own premises might a not-fit-for-purpose Victorian town house-style building used for classes, to property professionals selling properties off plan on the international markets even though the city like many others in the UK has a housing crisis. Is ‘the magic of Cambridge’ (a phrase repeated several times today) a dream that is too good to be true?

Cambridge is a small city but a fast-growing one

Again, a phrase repeated several times today. Yet can the benefits – in particular the soft benefits that those promoting the city speak of, such as Cambridge having close-knit communities with only a few degrees of separation, continue as the population within our 1935-era boundaries heads towards 150,000 (if it isn’t there already?)

This is why I ask the question of how Cambridge can spread the economic wealth and benefits not just to the surrounding market towns, but to the larger towns and small cities through new, and significantly upgraded rail infrastructure alongside the long term institutional partnerships that need to underpin them? I looked at the example of two under-rated historic county towns of Northampton and Bedford in this blogpost. Cambridge is at a point with its sci-tech parks are at capacity, & the speculative bubble means that land which could be better used for the social, environmental and civic needs of our city gets turned over into science parks. Wouldn’t it be better to have a policy that supports spilling out some of those firms into places like Northampton and Bedford that have their own unique town centre riversides and the space for firms to grow? Not every business function needs to have a three figure postcode that begins with CB. There’s a strange irony that as we’ve moved from snail mail to email and social media over the past quarter of a century, the branding of the postcode in Cambridge has become more important.

Cambridge is still failing its teenagers and young people in the 2020s just as our city failed my generation of teenagers and young people in the 1990s

Both Hilary Cox Condron and architect Thom Holbrooke told the Congress of the Academy of Urbanism this at the Cambridge Union building in the morning session following Prof Neely’s introduction with local council executives. Both of the former lived through Cambridge in the 1980s and can remember more about it than I can – such as the decline of The Kite (where The Grafton Centre is), now a familiar feature of Cambridge University’s introductory architecture courses. Every so often I bump into their undergraduates in the Cambridgeshire Collection and end up taking them through some of the wider local historical background and human histories beyond the architectural plans. As it turned out this evening at The Guildhall I had my paper copy of the 1976 proposals made by residents on how to regenerate the area (I’ve digitised it here – note the design principles) and ended. up giving the High Sheriff of Cambridgeshire a crash course in its local history in about 60 seconds under the watchful eye of The Mayor of Cambridge! As the Mayor reminded us, the new North East Cambridge redevelopment plans will be known as Hartree – named after her last-but-98 predecessor Eva Hartree, Cambridge’s first woman mayor. Note that 1924 will be Eva Hartree’s centenary year. (Eva Hartree later became the President of the National Council for Women, giving this speech in 1936). I’ve let the developers (whose representatives were at the Congress) know that they may want to commemorate this in a big way.

Are there any students out there willing/able to do a research project on how Cambridge is marketed, and the ‘before/after’ perceptions of those being marketed to? Whether language school students, people moving to the area, to those investing financially in the local economy? What vision were they sold? By whom? To what extent is that vision matching our reality?

Food for thought?

- Follow me on Twitter

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small subscription or donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge.