TL/DR? The responsibility rests with ministers who signed off an over-complicated system of governance that makes it very difficult for the public to identify where the real decision-making power resides (As your MP to write to ministers on how they will simplify the governance structure of Cambridgeshire to improve accountability https://www.writetothem.com/)

Before starting, I declare an interest as a paid up member of CamCycle – previously known as the Cambridge Cycling Campaign. After all, walking, bus travel, and cycling are my main means of transport these days. I’m rarely in a motor car – even though I learnt to drive on the mean streets of CB1 in the late 1990s. Most of my driving lessons involved a fair amount of controlling traffic-jam-fuelled road rage as well as 3-point turns! Driving like in the car adverts was something I never experienced!

As I’ve mentioned repeatedly, ministers are responsible for the deciding the structures and systems of local government. Major overhauls of local government have been talked about every so often but ministers since the early 1990s have refrained from such things because of how the attempted overhaul of local government finance – the Poll Tax, brought down Margaret Thatcher. The temporary measure that followed – ‘Council Tax’ indexed council tax bills in bands to the value of homes in 1991. And it has been that way ever since because ministers – as they stated in response to the House of Commons committee responsible for local government – said it would disproportionately impact on asset rich, income poor elderly people. (As if it was beyond the capability of central government to come up with a system that could account for this!)

“Why did the audience groan at the King’s Hedges hustings when cycling was mentioned in the debate?”

You’d have to ask them – and those who have been canvassing for today’s by-election for that response. The big picture fault does not rest with either the residents or CamCycle – rather it is with the broken systems & structures of local government and local media that we are currently burdened with. Furthermore, the structures of the former have been with us for a couple of generations, so it’s very difficult for anyone under the age of 50 to imagine what an alternative system of public service provision might be like. By that I mean in-house provision rather than contracted out.

The origins of this system – know in policy circles as New Public Management, became a hot topic as the Conservatives undertook a major programme of privatisation – making a series of promises about how much better things would be. (See some of the digitised items here). We’re now at a stage where new generations of campaign groups such as We Own It are now in a position to challenge the promises made with analysis of long term historical data to support their conclusions. Buses, trains, water, energy – all of these have come under the microscope.

“What’s this got to do with blaming CamCycle?”

One of the other areas of outsourcing was local government functions. In the 1960s there were a number of functions that councils delivered directly with council employed and unionised staff. These included the architectural design of council houses and public buildings – in Cambridge’s case it was Gordon Logie. Some of his work which I blogged about here is featured in the 1972 book on Cambridge New Architecture, including the soon-to-be-demolished Kingsway Flats. Which makes the analysis from the time all the more interesting as it shows what assumptions he was working to – and enables historians, contemporary architects, and local policy-makers to understand what the flaws were.

One of the many criticisms of outsourcing so much previously in-house functions is institutions inevitably lose their corporate/collective memory. Furthermore, they lose the capacity to scrutinise what comes back to them in terms of proposals for specific pieces of work – whether redesigning road junctions to building a new community centre and housing development. If councils are using a different set of consultants each time, or if the consultants who submit the best ‘value for money’ bids are also not interested in doing anything more than the bare minimum that the law requires, what can residents do? After all, Smarter Cambridge Transport was ground down by the refusal of the GCP officers listen – even to highly technical and specialist comment. I got ground down so much that I put my name on a ballot paper in Queen Edith’s calling for the GCP to be abolished.

One of the consistent complaints from active travel campaigners is that Cambridge City Council has not employed a full-time qualified cycling officer in the Greater Cambridge Planning Service – in part because the councils are so cash strapped they cannot afford to. One city-wide response was the growth of CamCycle over the past few decades. It wasn’t just because of this one issue with the council, but rather a growing awareness of climate change and air pollution – as well as continued traffic congestion and casualties on roads and pavements.

Because of the very limited capacities of local government – especially after over a decade of cuts and austerity, the in-house capacity to scrutinise and challenge developers over their designs simply is not there. As a result, it’s left to self-organising groups such as Cambridge Past, Present, and Future, as well as CamCycle, to compensate as best they can through their own members’ resources to do the best they can. And they can only go so far when you have huge financial interests who can bring the most expensive consultants to bear – hence the huge sums extracted from the granting of planning permissions. Which reminds me – the Romsey Labour Club case is still dragging on, the developer having appealed the refusal to cram more rabbit hutch-style units onto the site. See https://applications.greatercambridgeplanning.org/online-applications/ and type in 22/01432/FUL into the search box. I’ve written about it in previous blogposts, one of the latest being here.

Cycling and car driving don’t mix – and neither do shared narrow footpaths and cycleways.

We have more than a few of the latter on my side of town. While the guidance from central government has been updated – widely regarded as a significant improvement with which local councils can hold developers accountable to, the massive backlog of work combined with the lack of funding and industry capacity to carry it out means we’re left with the inertia of broken infrastructure that inevitably designs in conflict between the different means of mobility. One example is… Cherry Hinton Road!

Above from Cambridgeshire County Council 2019.

As things stand, it’s still not a segregated cycleway, but at least the proposals do something. Sadly they were postponed indefinitely because of utility companies finding out their infrastructure below the dutch roundabout on Queen Edith’s Way would require far more work. (Which personally I think they should have paid for the whole lot, but hey, broken governance systems…)

What’s striking is that CamCycle seem to get blamed for things that

- are outside of their control eg the behaviour of *all cyclists* (it’s a bit like blaming the AA or RAC for the reckless driving of all drivers convicted of motoring offences irrespective of who they have breakdown cover with – if at all)

- they opposed both at consultation stage – calling for significant improvements not just for cyclists but for all road and pavement users.

- they are not responsible for – i.e. they are not the final decision-makers.

Note the organisation has over 1,600 members, many of whom are active and who respond to consultations.

Interestingly, opponents of the Sustainable Travel Zone put forward by the Greater Cambridge Partnership managed to organise themselves very effectively (irrespective of what you think of their views) which resulted in nearly all of the candidates at the City Council elections having to speak out against the original plans. The one assumption that GCP senior officers made time-and-time again was that the councillors on the GCP Board would rubber-stamp anything that was put in front of them. One of the acid tests at the looming general election for all four seats in the south of Cambridge (Cambridge City, South Cambs, East Cambs, and the new St Neots and Mid-Cambs) is what should become of the GCP.

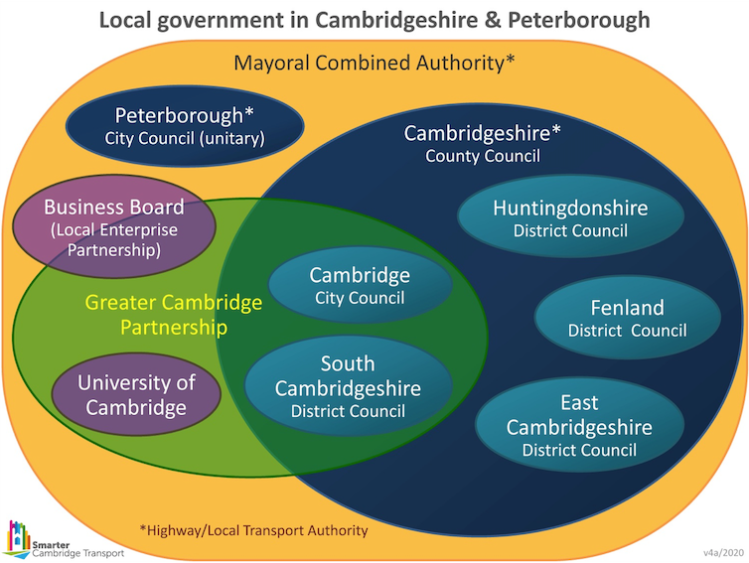

I’m not going to repeat what I’ve written about our broken governance structures. Anyone unfamiliar with them can see the reaction of international visitors at the Academy of Urbanism Congress 2023 in Cambridge when I showed them some diagrams. Put simply, a streamlined unitary council for the Cambridge economic subregion, and a separate one for Peterborough & Fenland would work far better for the general public, and make things much more clear as to the political accountability for major decisions, rather than the mess we have at present.

Furthermore, I believe there is a strong case (as part of the overhaul) for significantly improving and expanding the town and transport planning functions to bring back in house a host of existing functions currently contracted out through public procurement – and having those posts funded through a wider range of taxes – in particular weighted towards the wealth being generated in the Cambridge sub-region. If the sci-tech bubble wants to expand, they should be taxed far more heavily than at present to pay for the infrastructure needed. Interestingly ministers may well find some support for such a move because some in the sector have identified the lack of capacity in local government in a range of functions as a systemic risk to their ambitions. Levying a tax or three may have the dual benefit of reining in their ambitions for rapid growth and also pay for the world class infrastructure that the existing proposals from the Combined Authority, GCP, and ministers is not going to provide.

Involving the wider public in debates about the future of transport in response to the climate emergency

What do you do when the roads and rails melt in heatwaves?

Some people quite understandably state that other countries don’t seem to have problems with melting roads and railways and they have much hotter summers. The reality is somewhat different – it just depends where you get your news from – or rather what the mainstream news providers choose to broadcast. Pick a hot country and type ‘railways melting’ (eg India because of its extensive rail system) and you’ll find news reports of extreme heat melting rails. Hence the climate emergency presents civil engineering and metallurgical challenges too.

One of the consistent themes that comes back whenever I post updates on proposed developments is the sense that what’s happening to Cambridge from the perspective of more long-time residents is that the changes are being imposed on the city by someone/something else, and their views are never accounted for. I try to explain that this. is something that needs to be solved by national government, but the reality is that national government is even more broken so the problems won’t get resolved and we’ll carry on. Again, this is not a new problem – half a century ago Skeffington and chums published their report on People and Planning. (You can read it here)

Above – the intro from People and Planning (1970) HMSO

To what extent have things improved? Is consultation just a tick box exercise or is it a genuine attempt at shared problem-solving involving those most affected by the decision/s being taken?

My take is that consultation systems currently used in both central and local government are broken, and are not fit for purpose to meet the needs of society in the 21st century. The NIMBY / YIMBY split is a reflection of that. Furthermore, the Grenfell Inquiry’s evidence sessions exposed a broken construction industry further undermining public trust – already shaken by experiences of poor construction in newbuild estates. (To the extent there are accounts documenting cases – one with nearly 100,000 followers).

What would a consultation system that involved the use of imaginative shared problem solving methods have resulted in?

We can only wonder.

If you are interested in the longer term future of Cambridge, and on what happens at the local democracy meetings where decisions are made, feel free to:

- Follow me on Twitter

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge.