The Commission on Political Power is inviting submissions to their inquiry on improving citizen engagement with what looks like Central Government. I’m looking at the role democracy education can play in it from a local perspective, and what the existing limitations are.

This stems from a post by Alexandra Hall Hall, a former diplomat stationed out in the US just after the EU Referendum.

To get a sense of how big the challenge is, we need to look back a century ago to when universal male suffrage was brought in as a result of the sacrifices made in the First World War. It would be another decade before the Political Establishment removed the ban on the disenfranchised women in 1928. One of the arguments *against* granting universal suffrage was the lack of education of the majority of the population.

Above – J.H.B. Masterman (1920) in Cambridge Essays on Adult Education

Further down the page he also cautions against the rise of demagogues

My point is that we have been here before.

Just under different circumstances.

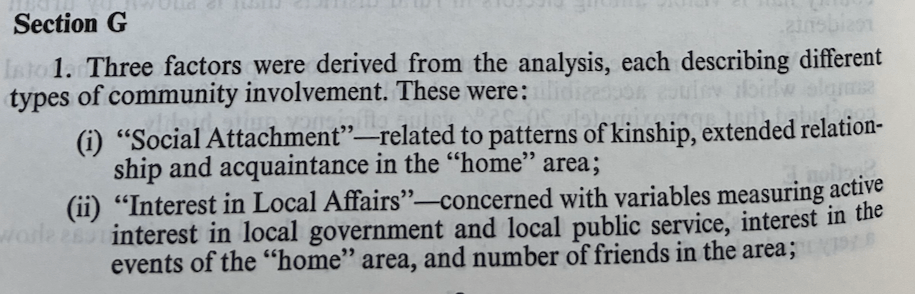

In 1969, the Royal Commission on Local Government published its community attitudes survey (see this thread for the summary findings). Essentially it was an extensive opinion poll of over 2,000 people and its findings make for interesting reading for anyone interested in strengthening democracy today, over half a century later.

Around ten percent of people are highly involved in community life – which encompasses local democracy but goes far beyond it as well.

This correlates with findings from The Henley Centre from DCLG back in 2008.

Above – This is from a report called “CLG Empowerment” by the Henley Centre which I acquired from a Freedom of Information request 10 years ago. It came with the disclaimer: “The results were a useful addition to the evidence pool, and informed community empowerment policy. However, the policy framework has now moved on.”

Assuming the above cohorts still apply, what methods of citizen engagement would be most effective for each different group?

Much as I would like to see democracy education evening classes and workshops in every town as part of a new lifelong learning offer for the public, those alone would not solve the problem

Rebuilding trust after it has been repeatedly shattered

Examples of where political trust has been broken over the past generation:

- The Iraq War II – WMDs

- MPs’ expenses

- Tuition fees for higher education

- The EU Referendum

- Brexit benefits

- Covid corruption

- The conduct of Boris Johnson as Prime Minister in the Commons and the breaking of long-standing conventions without serious sanction.

There are also many local examples of where trust in local democracy has been shattered, including:

- Controversial candidate selections for elections

- Contracted-out services failing to deliver on contractual responsibilities

- Dishonest and/or poorly-communicated consultations

- The establishment of governance structures that have broken lines of accountability

The Political Establishment – in particular political parties that have been in government in recent decades has no right to expect the general public to be familiar with democracy and the law when it has failed to provide the comprehensive means by which to learn about it.

You’ve heard the phrase: “Ignorance of the law is no excuse!” Yes it is if the authorities responsible for its creation have not provided the means by which the public can learn about, and educate themselves about it. Interestingly, some of the most useful examples are books aimed at children!

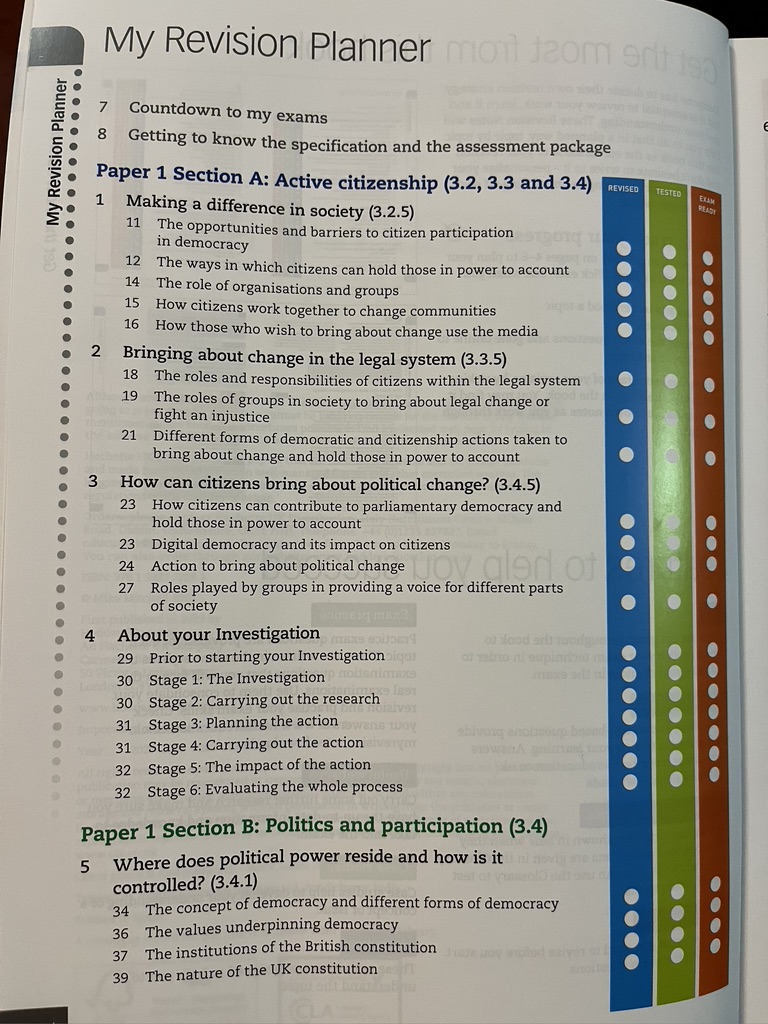

The closest we have in terms of a citizenship syllabus for adults is the GCSE in Citizenship for 14-16 year olds.

Above – the contents pages from Hodder’s latest edition of its revision guide. Which items would you include in a syllabus for adults? What is missing?

One important example of this was the establishment of the driving theory test in the 1990s. In the olden days you could simply write to your county council to get a driving licence. Then driving tests were invented, and then the written test was brought in. Standards did not stay still.

I won’t repeat myself on all things democracy education – something that could and should form part of a wider system of lifelong learning that could incorporate a whole host of positive things for adults, including health education and the establishment of community venues where people would choose to be. Back in 1968 the Derby and District Branch of the Workers’ Educational Association had a go at designing one. You can read about it here.

“I don’t have the time to do party politics!”

Few people do.

“Membership of the Conservative, Labour and the Liberal Democrat parties has increased to around 1.5% of the electorate in 2022, compared to a historic low of 0.8% in 2013”

Commons Library 31 Aug 2022

It’s not just party politics – it’s also community life generally. In my commuting days in the civil service I lost three hours a day minimum travelling to-from work (Cambridge-London). One of the reasons for leaving the civil service was that I realised. I had no social life and was just ‘living to work’. I would sleep through most of the weekend, and started to ask what the point of it all was if all I was going to do was to spend the next quarter of a century doing the same. In the meantime my city was changing around me but without me.

“What are the time barriers stopping people getting involved in local democracy and engaging in central policy making?”

If we assume that workshops and evening classes are a policy response (there are others) to the lack of knowledge, we also must consider the time needed to learn that knowledge. I remember talking to a senior government lawyer in my civil service days who repeatedly advised policy teams that the Government Legal Service staff needed enough time to consider requests for advice – i.e. not a 30 minute turnaround! The same applies here. It’s all very well putting on consultation events – as I seem to be spending more time at these days! But why is it that such meetings are predominantly full of middle-aged and older people? Where are the children and teenagers? It’s their future! Where are the young adults and graduates? Where are the parents with young families?

This is where local knowledge is essential. Because for all we know, the willingness might be there but the accessibility – whether long working hours to poor transport systems making it difficult for people to find the time, to compensating for under-funded caring systems may mean that some of the biggest positive impacts might not come from direct policy responses, but from indirect ones. As I found out the hard way, sitting in an office in central London is not the best way to find this out.

There’s a role for employers too – they should make it a core part of their business to ensure their staff know where they and their company sit within the economy and society

What would it look like if firms went beyond traditional ‘corporate social responsibility’ and created cultures of civic responsibility? From the basics of encouraging people to vote on polling day to subsidising lifelong learning courses for staff (which would have the beneficial effect of stabilising the finances of the learning institutions)? I come back to Dorothy Enright’s example in Cambridge in the 1920s where she surveyed all of the major employers in Cambridge before coming up with a course prospectus for adults on what is now the Cambridge branch of Anglia Ruskin University. Colleges that run basic skills courses could go further with their learning materials, commissioning content providers to come up with real life examples whether it be reading new/recent health guidelines from NHS providers for improving reading courses through to number-crunching election results for improving maths courses.

By making the scrutiny of policy decisions feel normal to more of the general public, and providing them with the means and knowledge to feed back into the policy-making processes, could this help improve the public’s understanding of democracy as well as leading to improved public policies? (And also increase the incentive for existing politicians to behave better, and for higher calibre people to put themselves forward for election?)

That last bit might be asking a bit too much!

But it’s food for thought….isn’t it?

If you are interested in the longer term future of Cambridge, and on what happens at the local democracy meetings where decisions are made, feel free to:

- Follow me on Twitter

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge.