The Irish Playful City social media feed landed this one on me – and it resonated immediately but not for the most obvious reasons

Coming back to that phenomenon I’ve written lots about over the years, the tweet below landed a few minutes ago.

One of the sentences from the article that appears at the end should have been inserted at the top. And it is this:

“Not everyone can live near their friends, much less within 15 minutes of them, due to the usual barriers like housing access, job availability, mobility opportunities and family ties. But there are city-level interventions that can make the choice easier to make.”

Holder (2023)

Part of me was like: “Well of course it does!” when I read the headline, but then I was reminded of a conversation I had with a local community activist in Queen Edith’s who recently moved out, and who I had been at secondary school with. She reminded me of how she had been able to stay in touch with a whole host of people we had known since school, whereas because of both decisions I had taken and also the demands of academia and work, I had not. Furthermore, when I look at the backlash within academia about the neo-liberal model of higher education and the negative mental health impacts of it, so many things click into place.

For those that leave their home towns to go to university, there are two major social disruptions / breaks that they/we have to cope with. The first is experiencing the majority of your cohort upping sticks and scattering to different parts of the country, if not the globe, and the second one being you as an individual being one of them finding yourself in a new and unfamiliar setting. In my case I experienced an additional one of leaving school at 16 to move to a separate sixth form college, and then taking a year out knowing I was not ready to go to university at the time of completing my A-levels. The third break is when everyone graduates and heads off (again) in different directions.

Combine that with a neo-liberal globalised economy whose wheels are coming off (if the environmental symptoms are anything to go by) and you end up with mentally high-pressured and exhausting workplaces in the face of extremely high rents in cities where many of the so-called ‘graduate level jobs’ are, and an expectation to ‘make it’ in metropolises that never sleeps. (I’ve seen Euston Road at 5am – it’s full of motor traffic and not a scene I want to see again!)

Now switch over to those working flat out in physically demanding minimum wage jobs in zero hour or temporary contract-after-contract who, for whatever reasons never had the opportunities to leave their home towns – or if they did were not in the best of circumstances. The reports of London Boroughs ‘exporting’ residents on their social housing waiting lists to towns and cities far away is not new – see Shelter from 2017 here. When thinking why this happens, think of the planning system that enables something fixed in supply (land) being used for non-essential developments [eg luxury apartments under-used by jet-set multiple property owners for example – Billionnaire’s Row coming up time and again]

Loneliness can manifest itself in very different ways – as I’ve found out the hard way multiple times.

“What if we had a 15 minute city for friendship?” asks Sarah Holder for Bloomberg

Understandable desire, but isn’t that just people living near their friends like when most of us are at primary school?

The opening remarks would probably strike most readers as common sense – eg living closer to someone increases the likelihood that you’ll see them [all other things being equal – that infamous refrain of the economist].

“Cities around the world are contending with what the US Surgeon General recently deemed a “loneliness epidemic,” and one of the public health proposals to solve it is to build social infrastructure that facilitates more human connections.”

Holder (2023) for Bloomberg

“What is social infrastructure”?

Good question – one that academics and policy-makers are still trying to figure out, as Prof Diane Coyle stated in her paper “Healthcare as social infrastructure” in 2022 – one that covers a very wide range of issues and concepts. Prof Coyle writes:

“While there is no settled definition or description of social infrastructure, here it is taken to mean long-lived assets in social sectors (such as health, care, education, justice), where there are significant externalities, and hence whose provision is generally in large part organised, regulated and/or provided by the state…

… social infrastructure includes both tangible assets (such as hospital buildings, MRI scanners, ambulance fleets, research or diagnostic laboratories) and intangible assets (such as R&D, health software, management capabilities or other organisationally-embedded knowledge).”

D. Coyle (2022) Healthcare as social infrastructure: productivity and the UK NHS during and after Covid-19. Working Paper No.017, The Productivity Institute. p10

Social infrastructure could mean a venue that functions as a community centre – i.e. something that you could point out as a building on the high street so to speak. At the same time, it could be the collective knowledge of a group of people interested in a specific subject. The knowledge of your local branch of beekeepers is part of our social infrastructure – trust me you’ll know about it if you find a swarm of honey bees gathered outside your back door!

One of the things I’ve become more acutely aware of is the sort of tangible social infrastructure that developers are proposing for new large developments:

- A place called “The Hub”

- Yoga classes

- Pocket parks and/or a gym

Above – a consultant’s view of an average day on a new Beehive sci-tech park, from their consultation event last week. You can immediately get a feel for the target audience.

And there was me thinking it was the robots that were supposed to do the chores, enabling people to do the more interesting art and creativity things…!

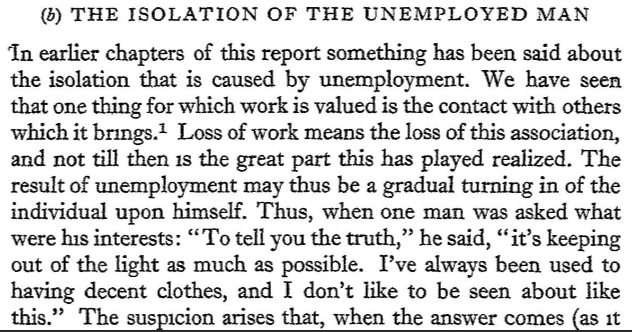

Yet as I wrote recently, cloned items don’t suffice for comprehensive facilities that a neighbourhood, a district, or a city needs in order to meet the multiple needs of the people who make it what it is. Don’t get me wrong – the new large concert hall that I want, on its own won’t either. As a building and the people who run it would both need to function as inclusive anchors – easier said than done. That lesson comes from the 1930s in a huge piece of work where the woman that did the hard work seems to be have been forgotten somewhat: Men Without Work – A report to the Pilgrim Trust chaired by the Archbishop of York. The person who drove the research was Miss Eleanora Iredale, the secretary to the Archbishop’s Committee for the Unemployed.

Above – Miss Eleanora Iredale from Guilford Cathedral / W Dennett

That inquiry was focused on the longterm unemployed – a social curse of the 1930s that drove the politicians in the postwar era to bring in radical policies to avoid its repetition. In his preface the Archbishop writes:

“Not only have the headquarters [of the National Council of Social Service – now the NCVO] given generous help, but the many contacts with their local representatives and with the Wardens of the Colleges for Adult Education were invaluable. [my emphasis].”

Men without Work (1938) Archbishop of York’s preface

Miss Iredale (Who I’m choosing to credit as the lead writer/editor) wrote:

Above – The Isolation of the Unemployed Man, p286/297, in Men without Work (1938)

What she does is gets inside the mindset of the longterm unemployed, and how sending them to whatever voluntary or state-sponsored centres alone could never be enough. It’s an historical lesson that ministers since then never did, or are yet to learn.

This finding was particularly striking.

“…isolation, in prosperous places, is not only an effect, but a cause of unemployment; as though the man with no social ‘‘backing” loses heart more easily and drops out of the race sooner than the man who has the support of family life or other associations behind him.”

The Isolation of the Unemployed Man, p287/298, in Men without Work (1938)

Which you could say is me with/without chronic ill-health.

“One group of people in the sample whom isolation did not affect, were those who had retained active membership of some social institution to which they had previously belonged. Comparatively few of those who had played a full part in the life of churches or trade unions had dropped out of them as a result of unemployment.”

The Isolation of the Unemployed Man, p289/300, in Men without Work (1938)

While both the churches and trade unions are far less powerful and prominent in society compared to a century ago, the active membership of a social institution is not something to be overlooked. The major policy error that successive governments have made is they have under-estimated the importance of the relationships that local government has with their local voluntary organisations.

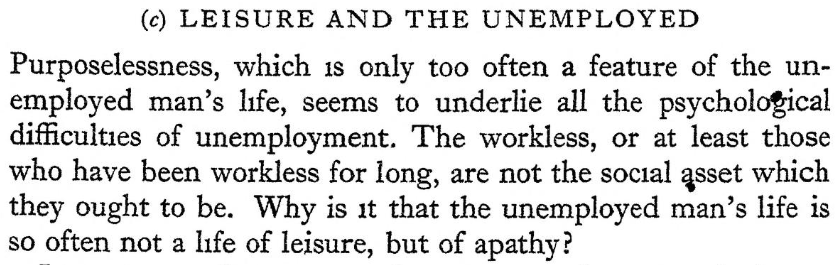

Breaking the stereotype of life unemployed in 1938 – and lessons for today

Leisure and the Unemployed, p293/304, in Men without Work (1938)

The mental health impact of forcing those unemployed to be looking for work 24/7?

Leisure and the Unemployed, p297/308, in Men without Work (1938)

If someone hasn’t done a comparative study on media portrayals of the longterm unemployed over historical eras, it’s waiting to be done. The next comment reflects the social class difference between the researchers/committee, and those being studied. They examine the moral decay – which by its definition comes with an airport’s-worth of baggage.

“The fact is that things which are unreal appeal to them simply because they are unreal. They escape into an imaginary world by buying, as a Deptford newsagent said, magazines to forget their troubles”.* The fault is partly in the conditions in which they live, but only partly in this. It is partly because an appetite for the unreal and the shoddy can be commercially exploited while genuine sensibility cannot.”

Leisure and the Unemployed, p295/306, in Men without Work (1938)

During my civil service days, a former Downing Street comms chief asked a group of us to consider what the most influential weekly publication was – this was back in 2007. We went through the various Sunday newspapers of the day, and then told us that Take a Break Magazine sold something like 600,000 copies a week – more than The Observer and Independent on Sunday put together. So if you’re a politician, who are you going to listen to more and why? (Turns out said magazine sells more than both the Observer and the Sunday Telegraph put together – although I don’t think that includes digital sales).

“What’s all that got to do with Cambridge?”

This matters for Cambridge because of the controversy over the proposals for the Beehive Centre redevelopments, where in particular people from working class backgrounds and people on lower incomes have huge concerns about the impact this will have both on employment and on their ability to access affordable essentials. Furthermore, if developers and planners don’t know *why* different cohorts of people buy the things that they do, it becomes easy to overlook providing for them in the face of the huge profits that come from redevelopment. What would a survey show of the demographics of the customers who use the supermarket cafes and restaurants? Get rid of them in place of up-market boutique brands and you’ve taken away some essential pieces of social infrastructure for a group of people that have a greater social need for, and less choice of venues to go to.

“But the climate emergency – we simply won’t be able to continue living as we do!”

And the big social risk is that we don’t take the wider public with us in that transition – the reality being that in order to adapt to the changing conditions, we have to involve a far greater number and diversity of people in designing that future than we have done. That involves education, discussion, debate, and sharing the task of defining the problems first before figuring out how to solve them. That’s why looking back at what the public said in the early 1990s about Cambridge’s problems (and how local and central government responded) is all the more striking – especially where the politicians did the complete opposite of what people asked for!

It’s not all in the planning. While you cannot plan for spontaneous actions, you can design in things that make them more likely.

For me the difference between the two is that with the former there are consequences if the plan does not come off. Designing something that makes a series of things more likely to happen is not dependent on a single pass/fail event. Holder in her article refers to that stereotype of scheduling appointments with friends weeks into the future.

“Is scheduling in appointments to see friends such a middle-class stereotype?”

Yep – telly said so.

“Any time you have to plan, there’s more possibilities that the planning itself is going to thwart getting together.”

Holder (2023)

Which is why I generally take the view of ‘I can work around your schedule’ if busy people say they want to meet up. But then the only clock I’m fighting against is my fatigue/CFS clock. Not an e-calendar full of appointments. (That doesn’t mean I don’t plan ahead – my planning ahead means scheduling Post-Exertional-Malaise days where I have to stay indoors to recover from activities that most other people take in their stride)

Social media was once good at facilitating friendships separated by physical distance

“If you don’t see them regularly enough, friendships decline very rapidly — within a few months, the quality of friendship starts to deteriorate,” he said. Digital communications and telephone calls can slow the decay, Dunbar allowed, but can’t stop it completely.”

Holder (2023)

What I’ve found is that the more driven by advertising that social media firms have become, the more they have crowded out conversations in people’s feeds with unwanted ads. The result? People end up drifting away because it feels like they are ignoring you – when in reality a tweak in an algorithm has changed what appears in your feed – eg because you are not ‘liking’ enough posts, so those people get de-prioritised. Combine this in my case with deteriorating health and a much-reduced physical capacity to travel and the number of multiple shared experiences that I have with people has reduced. Combine that with the lockdowns (The pandemic is still here) and my social life dropped off of the metaphorical cliff to the extent it is non-existent.

Take all of the above together, and you have multiple complex public policy problems to solve

An holistic approach to people with multiple needs – while creating an environment where people would choose to be.

I come back to my article from August 2022 about a new generation of lifelong learning centres. It does not mean building a campus-based university-style institution where everyone lives a utopian dream. I didn’t have the greatest experience at a campus-based university so can compare how the principles were supposed to work, and the realities – especially when support systems are not in place.

‘City leaders, architects and planners can invest in social infrastructure, like public spaces, parks, plazas, and libraries for gathering.’

Sarah Holder states what feels like the obvious, so what is it about our politics, governances structures, economic and financial systems, and legal systems that seem to make it so hard to build those tangibles (buildings and public spaces) and fund the intangibles (eg the community groups that might otherwise not run at all – such as youth clubs).

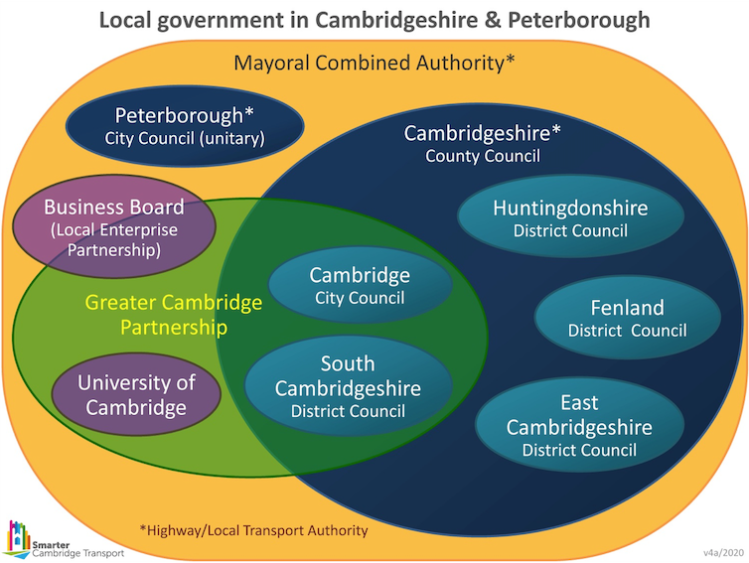

And as things stand, local government in England does not have the finances or the legal powers to ensure those support systems are in place. Look at the catastrophe that is the crisis of access in dentistry. Ditto GPs. No point in compelling developers to build surgeries and clinics if ministers won’t bring in policies to train up enough GPs and NHS dentists to fill them.

Back in January 2022 (18 months ago) I wrote about Cambridge’s cultural and social infrastructure deficit. How many of the developers are aware of that deficit, and how many are prepared to do more than the bare minimum to help reverse it? Because as I mentioned at the end of this article, some of the affluent private schools in Cambridge have built or are building splendid new facilities that happen to be far away from the homes of those who might benefit from ‘community access’ agreements – especially those that form part of planning permission.

The tough public policy – and party political questions revolve around the new policies that need to be brought in that makes the pro-social infrastructure policies the norm, rather than as it seems all too often, the exception.

Food for thought?

If you are interested in the longer term future of Cambridge, and on what happens at the local democracy meetings where decisions are made, feel free to:

- Follow me on Twitter

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge.