TL/DR? See the papers from the Inquiry into the Future of Lifelong Learning (IFLL), commissioned in the late 2000s.

Above – some of the papers produced for the IFLL.

The phrase according to the IFLL’s Sector Paper 5 – A learning City Perspective (click here, scroll down) came from when Southampton became a unitary council, and declared itself to be a learning city. Yet by the time the Coalition Government came into power, the whole thing had all but disappeared. Why? According to Martin Yarnit here the culture of silo-based working put ‘learning’ into the sphere of education and everyone else carried on as normal, even though the challenges our towns and cities were – and still are facing are interconnected and intersectional.

“Those of us who have helped to promote the idea of the learning city have to set aside our carefully designed frameworks and toolkits and get to grips with the learning journeys that cities have embarked on, using the language they understand if we are to have something useful to say in the future.”

Yarmit 2011

This raises one of the risks associated with my repeated calls for a new lifelong learning centre in Cambridge (although in my view it is a risk that can be managed, and does not diminish my case for it).

“What is that risk?”

The mindset that for every problem in society, there is a course or an evening class or a workshop that can be designed to resolve it. [What would it be like to have somewhere for those doing online courses (eg https://www.futurelearn.com/) to meet up and share learning given the rise of MOOCs?] It’s like all of those consultancy reports that we seem to hear about these days like we expend more resources on producing the reports than getting on with the desired task in hand – whether building a new community facility, a transport route, or a renewable electricity generating station.

Cambridge – an inclusive or an exclusive city?

“Well of course Cambridge is a city of learning – you’ve got the University!” I hear you shout. It’s also one of the most exclusive institutions in the world – which means that by its very nature it excludes people. The ecosystem that has built up around the University’s brand has become so good at excluding people that it has become the most unequal city in the country.

Above – this video was produced five years ago. Progress update?

Was progress even possible given the national political instability in Westminster under Theresa May’s second Government, the Pandemic, and then the catastrophes inflicted by the Conservatives not just on themselves but the rest of us as they ploughed through three Prime Ministers in six months?

Some learners are doing it for themselves

For example in the tech sector you only need to go onto Meetup, search in Cambridge (UK) and you’ll see how many learning-related events there are compared with other categories. One of my huge concerns about the direction of travel with social media is that big tech firms, in their drive to put ringfences around their brands, are breaking up the very things that make social media ‘social’ – in particular the ability to share event details easily. The impact that this has already had on me has been significant.

In another part of the spectrum – the institutional end, the IFLL paper on the learning city reflected the political era it was launched in:

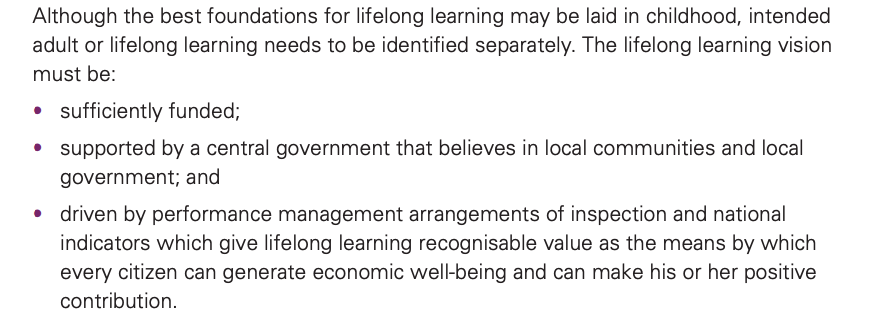

Above – IFLL – A learning City, p7

As we’ve found out, nothing seems to be sufficiently funded by the state unless you’re a chum of a minister. Furthermore, austerity has demonstrated ministers do not believe in local government – look at Michael Gove’s hasty and ill-thought-through intervention in Cambridge (along with the partial support to selected areas through his Levelling-Up funding). Finally, the performance management systems that the final point refers to were abolished in 2010 – only now have ministers realised the error of that hasty decision in a Cabinet that Michael Gove was in.

The paper on the learning city, which was written by Ian Sandbrook for the IFLL pulls out the traits of an effective learning city:

“Essentially it argues that an effective learning city should:

- “be explicit about promoting lifelong learning as an idea and encouraging people to

develop a sense of themselves as learners; - “encourage organisations and institutions (whether formal or informal) to incorporate

within their missions the City’s vision to create communities of lifelong learners

who recognise and value their learning, - “foster an understanding of progression and recognition and actively support

networks of providers and other organisations involved in lifelong learning to

collaborate in order to enable learners to pursue their learning pathways between

institutions and in so doing to build on previous experiences and achievements. - “systematically secure inclusive policies, plans and practice and review progress

annually to identify who is missing out; - “celebrate community and culture;

- “secure an appropriate range of learning activities and opportunities across the life

course; - “fund and support networks of learning development workers to encourage and

support people into and through learning. - “embed positive leadership of learning in local government and institutional

governance arrangements and secure genuine partnerships that create synergies by

aligning resources for common purpose.”

Employees of any organisation can find out how much money was allocated each year for training and development, and compare that with how much was actually spent. Chances are the organisations will have underspent. If anyone wants to do an comparison institution-by-institution over the past five-ten years, see https://www.whatdotheyknow.com/ and ask away.

Cambridge’s culture of learning – and its institutions of learning feel fragmented, discrete, and siloed.

This comes back to the point Mr Sandbrook makes in the IFLL’s Sector Paper 5 – A learning City Perspective (click here, scroll down) on page 9. In particular his differentiation between ‘lifelong learning’ (a continuous process) and ‘an adult learner’ (an individual who has enrolled onto a learning programme). Institutions and politicians talk about the former when in reality they are measuring the latter. That’s why Combined Authorities have such a narrow focus on basic skills and vocational training. Take Cambridgeshire & Peterborough which controls our Adult Education Budget. The CPCA states its aims are to:

- Improve life chances and increase the social mobility of all our residents

- Improve prosperity for all by increasing productivity of our workforce through upskilling

- Enable unemployed residents to reskill and gain good employment

- Improve the quality of life through an enriching lifelong learning offer

Yet lifelong learning isn’t something that just happens in the classroom. Therefore there’s an inevitable tension between allocating the entire policy area into a ringfenced budget if some of the things that might improve people’s access to lifelong learning opportunities don’t involve more courses, but things like improved bus services to community centres or free/low cost childcare facilities. How do you respond to those if you are a public sector organisation who does not have control or influence over those policy areas?

“Cambridge” assumes a very high level of skill and talent in a host of university-related fields

– to the extent it can make it very difficult for those with little knowledge, or those who want to start as adult beginners, to make that start.

Take classical music for public performance as an example. The highly acclaimed Cambridge Philharmonic Orchestra has a series of events coming up. Note they are inviting people to try out for their chorus – especially under-35s (which reminds me of another issue about cost of living in Cambridge!) Now, thanks to the now sadly on-hold We Are Sound/Dowsing Sound Collective, I should be confident enough to give the chorus a go myself. I was lucky that in my time in London we had the Mary Ward Centre that enabled people to get back into music. Or get into music for the first time. Ditto City Lit in London. For a city as endowed in classical music as Cambridge is, it’s soul-destroying that we don’t have anything like those set ups here. We should have a late-starters’ orchestra like East London does. We don’t.

“Your point being?”

What is the pathway for anyone wanting to learn as an adult to progress into joining a group like the Cambridge Philharmonic? That’s not something that either a local council or a single music group can solve alone. That’s a city-wide, even county-wide issue. We used to have two men and at least one woman of vision after WWII who went after that problem: Ludovic Stewart and Brinley Newton-John (Olivia’s dad), and Molly Gilmour – who founded the Cambridgeshire Holiday Orchestra.

“Lessons and practice are solo activities for children but what brings it all to life for them is the fun of playing good music with lots of other children.”

Cambs Holiday Orchestra – History

It’s emotionally painful reading that because when I was at school in Cambridge, no one asked if I wanted to take part, let alone encouraged me. It was the opposite with exams – which resulted in me packing it all in by the middle of year 8. Continued austerity throughout the 1990s along with the continued messages of ‘exams come first’, plus my association of classical music and the church together meant that by the end of that decade I saw all three concept – exams, classical music, and institutionalised religion, as oppressive forces which I wanted nothing to do with. Which brings me to barriers:

- I’d struggle participating in a music group that had church music in its repertoire (you can see why I find December an awkward month! (I don’t blame the orchestra for this))

- West Road Concert Hall does not have direct bus services to most of Cambridge’s residential estates – the U-service being designed and funded by The University to serve mainly its own communities rather than the wider city. (It’s not the orchestra’s fault that we don’t have an international standard very large concert hall!)

- The lack of a city-wide pathway for adult learners to go from beginners to the standard needed to get to a level required for public performance.

The last point is also one of the reasons why I’d like to see The Junction expand its offer of learning to include paying adults – as a means to raise money to re-invest in its charitable activities, in particular for young people. With South Cambridge – one of the most sought-after residential areas in the country to live in, on its doorstep, I’d like to think it wouldn’t have a shortage of paying participants.

Under the current system, spending taxpayers’ money on music is inevitably seen as a ‘nice to have’, but not something that can have money spent on it if it means reduced funding for basic skills training.

Compensating for generations educated in a social-class-based system

I’m sure I wasted more time having to learn stuff I’d never need in life at school, college, and university than the really important practical things such as those summarised in Mylene Klass’s book from 2022. See the chapter headings below:

Above – They Don’t Teach This at School

Remember that for pre-2000s teenagers, the social culture of the time would have been so great that some of the things listed would not have been possible in the way we think of them today. Furthermore, there are things in that list which simply did not exist a generation or so ago – politics and the law are still trying to catch up.

In going through that list, which are the things that are suitable for learning within an institutional environment, and which ones are more suitable for a community or family environment? How do you ensure those that are isolated from all three are accounted for? We learnt this the hard way in the first lockdown where the collective response had to involve everyone with the threat of prosecution for those that did not. And that’s something we may not have captured in the learning: Just how did local councils and local communities ensure that everyone was covered?

One of the reasons why the list in Mylene’s book matter is the climate emergency. Do any of us feel prepared to deal with the sorts of catastrophes we’ve seen in continental Europe? Wildfires, torrential rain and flash flooding, structural damage to property? Because if it’s on a scale where permanent repairs cannot be made immediately, how many of us feel equipped and knowledgeable to make temporary repairs ourselves? I don’t. It’s worth noting initiatives such as the Norwich Men’s Shed are picking up in popularity as a practical means of dealing with multiple issues through the process of collective learning. It’s just my luck that the ones around Cambridge happen to be on the other side of the city. Because land prices are so high in South Cambridge, any site that might be suitable for such a facility is soon snapped up. That or the rents are so prohibitive that no such venture could establish itself.

So as a learning city…

Beyond formal academia and the sci/tech sectors, Cambridge is struggling. And we’re struggling mainly because our governance institutions are structured in such a manner as to make creating that conducive environment for learning all but impossible. Cost of land, cost of rent, cost of living, little spare time – there’s a ‘missing middle’ in our city of residents aged between say 25-50 who are collectively conspicuous by their absence in for example the community choirs popularised in recent years. (Not for nothing is the Cambridge Phil appealing to under-35s to get involved). But how much is this a symptom of our city being unable to provide the support mechanisms necessary for a generation that is squeezed at both ends – from childcare to caring for elderly relatives?

To become a better learning city…

We need to review what support mechanisms are in place, where, and for whom – then compare that with what the people of our city (incl. residents, commuters, students, and regular visitors) tell us that our city needs to provide to enable them to participate. And that may involve some difficult conversations for politicians and policy makers.

Food for thought?

If you are interested in the longer term future of Cambridge, and on what happens at the local democracy meetings where decisions are made, feel free to:

- Follow me on Twitter

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge.