The only qualification you need to become a politician is a mandate from the people at the ballot box – or so the various sayings go. Yet recent decades have exposed the limitations of this as one of the very few checks on an aspiring politician’s rise up the political ladder.

Prof Sir Geoff Mulgan of University College London was a prominent adviser in Tony Blair’s Government in the 2000s, being his Director of Policy (and later of the Prime Minister’s Strategy Unit). So if anyone knows the inner workings of Downing Street and comment on it with authority, it’s him. You can read his article linked below:

“Can democracies afford incompetent leaders? The case for training politicians”

I agree with his premise: Politicians need more, and better training than is currently available. Furthermore he picks out five themes that need exploring, which are:

- When in their career?

- What mix of knowledge and mindsets?

- What mix of internal and external knowledge?

- Learning as individuals or teams?

- Who pays?

“I thought we had a National School of Government!?!”

We did – I went on several of their training courses in the 2000s (hence the book!) Then after I left the Civil Service, the Tories closed it. Or rather the Coalition did.

“And the Royal Institute of Public Administration before that?”

Founded in 1922, closed by the Tories in 1992.

(Their old books can still be found, which shows a history & culture of lifelong learning and training that I fear we’ve lost).

“If training politicians is the answer, what is the question?”

“I have seen too many – particularly in the UK in recent years – who were completely out of their depth, wholly unprepared for the kinds of decisions they had to make.”

Prof Sir Geoff Mulgan 04 Aug 2023

Essentially it is: “How do we reduce the risk that new ministers enter public office for the first time who are completely out of their depth and unprepared for the demands of ministerial office?”

In Mulgan’s case, it is clear he is talking about holders of very high public office. I comment later on in this piece that training of politicians needs to cover a much wider range, including local government.

There is no ‘one size fits all’ response to how politicians should be trained (and. whatthat training should involve). I’m reminded of something that often comes up in online discussions on neurodiversity where we share our problems and challenges with the lack of proper support and treatment from under-resourced health services alongside how things like workplace structures and cultures are simply not cut out to get the best out of us. One common complaint is how many of us get referred for Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) even though more suitable treatments and therapies might have been discovered – ones that all too often are not available on the NHS. The point being that you can’t simply send politicians on a politics course and say “Done it!”

Mulgan – as a graduate of the Politics, Philosophy & Economics course at Oxford University (Cambridge University doesn’t do PPE!) gives an insight into the course’s founding and limitations.

“In the UK, a century ago, Oxford University created a new course – Politics, Philosophy and Economics (PPE) – designed to nurture a cadre of leaders. Many British prime ministers and ministers took it (as did I). But its emphasis on macroeconomics and analytical philosophy doesn’t sit well with a world of pandemics and climate change (which is why I went onto do a PhD in technology).”

Prof Sir Geoff Mulgan 04 Aug 2023

Not surprisingly, the list of graduates from that course is long, and cuts across political parties. As Mulgan asks, what do you do if the course content becomes so unfit for its original purpose in a changing world? Do you stick with its principles, only doing a standard refresh as with other courses? Do you change the marketing? Or do you replace it with an entirely new course based on the demands of the world today and tomorrow?

The course that Mulgan has been developing at UCL is their B.Sc in Science and Engineering for Social Change. You can have a look at the module list here – which makes for both fascinating reading, and also reflects the huge institutional, class, social, and financial barriers to the many teenagers interested in such a course.

In the latter case, Mulgan would concede (I think!) that his course is not aimed at over-21s who left school with few, if any qualifications, and who decided they wanted to go into full-time politics as a result of their working and life experiences – Angela Rayner MP, the Deputy Leader of the Labour Party being a good example <- this article from 2012 is from when she was a Unison trade union branch secretary.

“Isn’t Prof Sir Geoff Mulgan’s article focused on that very small cohort of people who aim for, and are successful at getting into elected high public office?”

That’s the impression I got from reading his article – although note that he states this is ‘work in progress’ as he seeks to undertake more surveys including of Masters in Public Administration courses – something I was looking into until my health imploded. (Hence my comments later on regarding accessibility – given my own significant chronic-ill-health-related limitations)

During my civil service days there was a group of us that started a PG.Cert in public administration in the late 2000s only the course content was hopelessly obsolete by the time we started because social media take up was having a huge impact and users were running rings around institutions, unpicking their actions, policies, and assumptions at will. In hindsight it was a course designed for a textbook-only age from the previous millennium, and was unable to adapt to the new era of austerity. I found similar with my economics degree in the early 2000s where some of the authors of the core textbooks found themselves compromised both the banking crisis [eg not declaring conflicts of interests in economics papers] and since then on their assumptions in the face of Grenfell [where the excellent cross-examination by Richard Millett KC and team revealed an entire system of policy-making utterly broken and corrupted by vested interests], and the climate emergency. The motives of Political actors and the actions of The State were almost written out completely.

“But lots more people are politicians than ministers of the Crown and their shadow ministers”

Backbench MPs for a start. All the way down to local councillors if we are to look at political roles in a hierarchy. That means covering the multiple types of roles that being. a politician entails. The skills needed to run massive institutions with large budgets and huge workforces are not the same as those needed to scrutinise a large organisation, run a campaign aimed at the general public, the listening skills needed to deal with delicate personal issues from constituents, or give barn-storming speeches at big rallies. And more than a few of those skills cannot be taught in the classroom.

The course that Mulgan and colleagues have developed will (I hope) be one of several sound responses to the problem he has articulated – one I agree with.

I saw first hand what happens when the House of Commons has too few knowledgeable research scientists on its benches – everyone goes through a very small band of MPs. In my case it was my local MP at the time Dr Julian Huppert (LibDems – Cambridge 2010-15). Too much work from the science world had to pass through him and a few others that really should have been spread more equally – but not enough MPs had the essential scientific training to pick up complex issues quickly enough in order to act fast.

Three years is a long time for a mature student to take out of the workplace to undertake. a programme of study that the UCL science & social change course outlines. Furthermore, the expense involved all but stops anyone but the wealthiest from taking such courses unless there are a substantial number of bursaries available – which there are not. With both inflation and a housing crisis, existing bursaries struggle to match the actual costs of studying. Therefore there is a huge residual risk that the course – interesting as it looks to be, may only be one that an affluent part of society can take advantage of. (Note this is *not* an argument for scrapping the course. It’s about dealing with the very difficult issue of inequality in society). Which brings us to the bigger challenge for public policy thinkers:

‘What sort of training offer and career path would you make available to a young woman in Angela Rayner’s position at the time she had been invited to get involved with the trade union branch of her employer?’

Since returning to Cambridge from London, I’ve been able to meet with and listen to people. I was at school with who did not go to university but who stayed in Cambridge – several with teenage and grown up children. I’ve reflected on how we were all failed in different ways by a system which for almost the entirety of our childhoods were under Conservative administrations. As I mentioned in a blog ages ago, one old school friend mentioned to me that most of us achieved our successes in life *inspite* of the educational institutions we went through rather than because of them. Which also reflects on the willingness or otherwise to stay in touch / make alumni donations. (I still get junk mail from my undergraduate university despite repeated requests. toleave me alone!)

This brings in the issue of lifelong learning – and one Prof Sir Geoff Mulgan and colleagues may want to invite the likes of the Open University, Birkbeck, and the Learning and Work Institute to take a lead on. Assuming those institutions accept Mulgan’s premise that politicians need more and better training – which inevitably means more options and better options than what has been available of late, they could research the lifelong learning strand in terms of part time courses and evening classes.

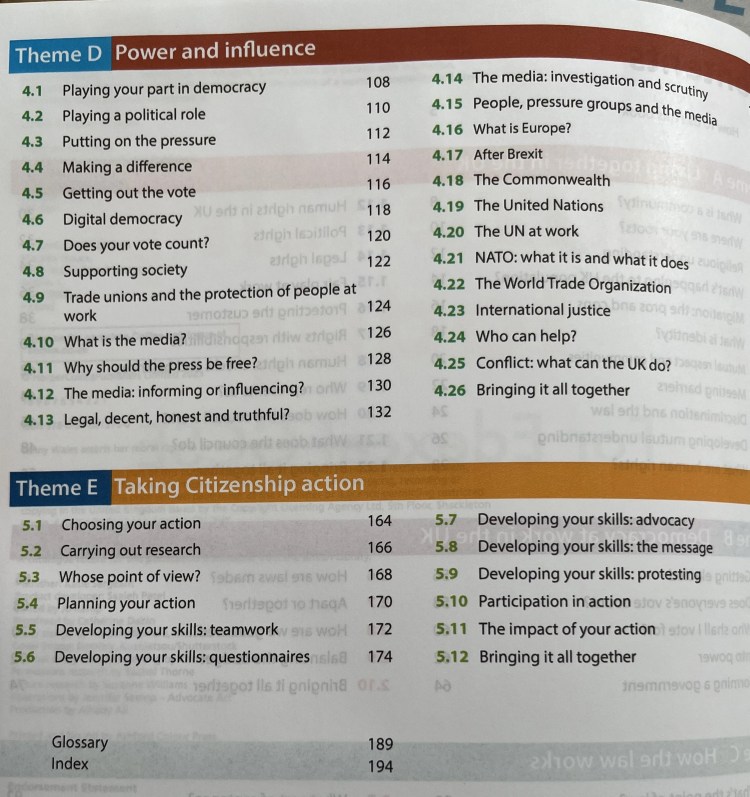

Which is all well-and-good, but does not deal with the almost complete absence of citizenship learning at school that my generation experienced throughout the 1980s & 1990s. Which is why I’ve said recently that Combined Authorities should explore offering the GCSE Citizenship Course as part of their adult education offers. Because when you look at what the teenagers of 2023 are learning, using Jenny Wales’ textbook and contents page as an example, what the teenagers cover over two years is comprehensive.

Above – by Jenny Wales – GCSE Citizenship Studies (2023) Collins.

If policy-makers are serious about getting more people involved in politics, this is one of the places I would start. I also think this should be combined with the construction of new lifelong learning centres – noting the call from the House of Commons Education Select Committee in December 2020 for a lifelong learning centre in every town across the country.

“A community learning centre in every town, individual learning accounts and boosting part-time Higher Education and employer-led training should be at the centre of an adult education revolution to tackle social injustice and revitalise the country’s economy, the Education Committee has said.”

Commons Education Select Cttee – UK Parliament 18 Dec 2020

Furthermore, the then Chair of the Select Committee (ironically now the Minister) Robert Halfon MP stated in the debate on the Government’s response in 2021:

“The strategy has four pillars. First, let us fund an adult community learning centre in every town. Community learning supports adults who cannot even see the ladder of opportunity, let alone climb it. In Harlow, we are lucky to have a remarkable adult learning community centre, and it will soon be relocated to the beating heart of the town

Robert Halfon MP. -15 Apr 2021

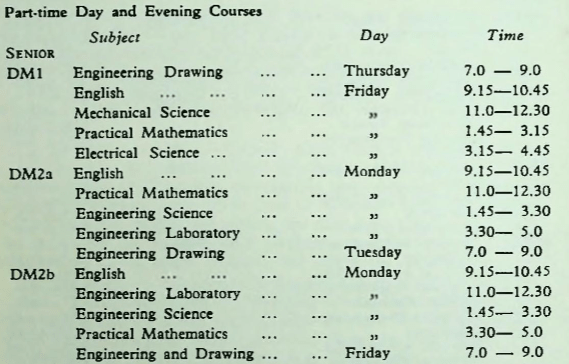

Cambridge used to have such an institution that carried out that function and furthermore it was as close to the city centre as the University and colleges would allow. This was the old Arts & Technical College – CCAT, that Dorothy Enright, the first woman to lead a technical institute in England built up on East Road. By the 1950s, that institution was teaching some of the very things we’re calling for today. I wrote about their comprehensive timetable here.

Above – you can browse through their timetable here – many courses designed with employers.

In the 1980s the college was effectively broken into two, with the vocational further education site heading to a site off King’s Hedges Road – today’s Cambridge Regional College, and the East Road site becoming first Anglia Polytechnic, and today Anglia Ruskin University. Hence my repeated calls for a new lifelong learning centre for Cambridge.

“To conclude?”

Good idea – run with it, and also ensure UCL is working with partner institutions to cover the areas that UCL does not have the capacity or legal competency to cover. Also, manage the risk of the course becoming socially exclusive.

Food for thought?

If you are interested in the longer term future of Cambridge, and on what happens at the local democracy meetings where decisions are made, feel free to:

- Follow me on Twitter

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge.