I spent the second year of my time at university living in accommodation that was eventually condemned as ‘unfit for human habitation’ by Brighton and Hove Council in 2001 – so I’ve lived it.

What’s astonishing is the utter failure of ministers past and present to understand the basics of the problem, let alone asking themselves how their various policies are making problems worse not just for students but local residents in the private rented sector competing for the same housing.

Like many other university cities, Bristol has a student accommodation crisis. Furthermore, the institutions seem either unwilling or unable to accept the scale of the problem that they are in part responsible for (“University intake is increasing and there is now a 25 per cent shortage of beds for students in Bristol.“ – Daisy Wigg for Tab Bristol 30 March 2023]”, or unable to come up with a comprehensive set of solutions that leaves both students and local residents angry.

“You’re beginning to see student housing moving into shortage across the majority of universities – not just the ones you read about,” said Martin Blakey, the chief executive of the student housing charity Unipol.

The Guardian 26 Dec 2022

It’s as if ministers and the cohort of executives running our universities are either oblivious to, complacent about, or resigned to the existence of the accommodation crises – one that is chronic/long term.

“Further research shows that by 2025 there will be a shortfall of around 450,000 student beds in the UK. Unfortunately these figures suggest the crisis isn’t going to disappear any time soon, unless universities, local governments and the housing sector work together to provide suitable measures.”

Chloe Carr for Essential Student Living – 24 Feb 2023

What’s their collective plan to solve it? Or does it reflect broken local government structures and systems that I’ve long complained about?

“Accommodation affects a university’s recruitment, its reputation, its future planning strategy, its local community relationships, and its work to propel its civic impact. Accommodation is also a critical factor in establishing with students the sense of belonging that underpins retention”

Higher Education Policy Institute, 24 April 2023

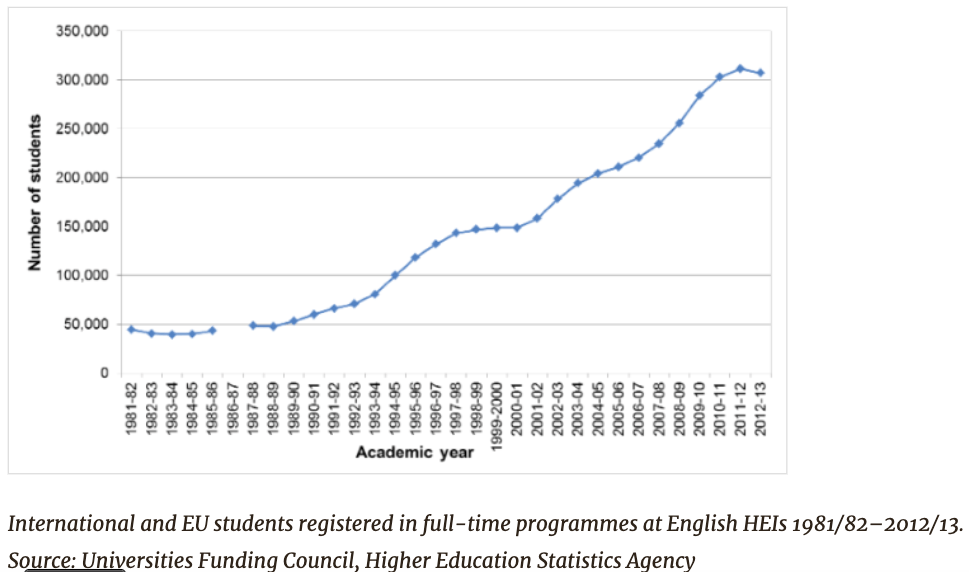

This is hardly a problem that has crept up on ministers or the sector. Numbers of students have been rising significantly since the arrival of John Major into No.10 Downing Street.

Above – from the IECF Monitor, April 2014

Ministers have chosen to disempower local councils when it comes to resolving housing issues.

It’s another symptom of the enfeebled state of local government in England. Part of it reflects an unwillingness from ministers to have an open and honest policy discussion about the powers of local government, the freedoms of academic institutions, and the accountability of both to the people of the towns and cities they reside in and are responsible for. In the end we’ve got the worst of both worlds – ministers holding the powers but refusing to do anything about it.

Most of you will be familiar with my repeated references to Parliamentary reports on unsustainable council finances (Commons LUHC 2021) and the overall broken system (Commons PACAC 2022) that means councils:

- Do not have the legal powers to restrict the growth of educational establishments, let alone place conditions on their growth such as providing the necessary accommodation for those students – with the ability to take legal action against such institutions in cases of non-compliance;

- Do not have the financial powers to ensure that their own local residential housing needs are met – ones that are essential for the proper functioning of towns and cities.

Furthermore, there is a boastful ignorance within the present political class when it comes to learning from the best practice from other countries when it comes to effective national policy changes that would enable towns and cities to solve their own problems rather than going cap-in-hand to central government all the time. The problem is that ministers seem addicted to the wasteful system of providing very small pots of funds that require competitive bids (that cost time and money to put together – resources that most councils can ill-afford). Another one was launched…yesterday.

“£10 million fund to open in early Autumn and help deliver government’s ambitions to restore optimism and pride in local communities.”

GovUK Press Release: 11 Aug 2023

“What is Cambridge’s situation?”

The Cambridge Centre for Housing & Planning Research carried out a study for Cambridge City Council which was published in 2017. You can read it here. (Top link is the full report, bottom link is the executive summary. Sadly, graphs showing trends of student numbers over time are lacking. As is data on Air B’n’B type rentals. From the Executive summary, we find that a very large number of student rental units (Purpose-Built Student Accommodation) should be built if only to get existing residential properties artificially converted into HMOs / student lets turned back into open market lets or sales.

Above – from the Assessment of Student Housing Demand and Supply for Cambridge City Council, CCHPR Jan 2017.

In the next few years they’ll have to commission a progress update. -not least for the emerging local plan 2031-40.

In the grand scheme of things, a more detailed housing study would need to consider a number of discrete/separate housing types:

- council housing

- social/affordable housing

- sheltered accommodation for older people

- sheltered accommodation for people with ill-health (I can see myself needing this in the not too-distant future)

- student accommodation

- the apart-hotel market (and the business needs that rely on it, along with methods for taxing the users and/or property owners locally)

- Air BnB-type lets

- hotels and guesthouses

- Long term private rental

- Home ownership with/without mortgages or secured loands

And that’s before we look at the types of business premises for the types of businesses that cities need in order to function – such as trade building supplies. And if we spiral out we get to things like the need for large open green spaces in residential areas, sports facilities (indoor and outdoor), community centres and arts/leisure facilities, small, medium, and large. The way that the local planning system seems to (mal)function is in a way that makes the designation of large facilities very, very difficult.

There are lots of books about the future of cities featuring international case studies, but the broken political system in the UK makes me wonder whether in our case the examples may as well be works of fiction. Because the structures of our systems – governance, political, financial, all seem to stop towns and cities from getting the nice things that are so important for the collective wellbeing of the people who make up those settlements.

Anyway.

Rant over.

If you are interested in the longer term future of Cambridge, and on what happens at the local democracy meetings where decisions are made, feel free to:

- Follow me on Twitter

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge.

Above – from AS Citizenship Studies (2009) Mitchell et al, Hodder Education, p231