Only 37 people have downloaded Qasir Shah’s paper for UCL (have a read here), yet his paper identifies the similar gaps I’ve been blogging about for ages. Given the way public policy works in the UK, elected politicians could put these findings to ministers and combined authorities in order to boost lifelong learning – and not just on citizenship.

Here’s one very striking quotation.

“A decade of austerity has resulted in adult education being severely underfunded, which it is argued has affected the most marginalized and vulnerable in society: those who need education the most as their only route to social mobility and social contact”

Shah, Q (2020) Abstract

This I can relate to. On most days I’m lucky if I can get beyond the end of my road. Today wasn’t my lucky day. A huge contrast from the days when I commuted to London from Cambridge, travelling over 120 miles a day every weekday in the late-2000s.

I’ve moaned about the artificially-narrow focus of adult education policy in England before. Both Labour and Conservatives (in and out of coalition) chose to keep funding and policy-making for basic skills training and lifelong learning for leisure in the same policy and funding area. That made it easier to argue for prioritising spending ‘taxpayers’ money’ on the former rather than the latter. Because ‘spending tax payers’ money on ‘middle class flower arranging classes’ is something easier to lampoon politically in advance of cutting any state subsidy. Even the late Frank Dobson MP used the flower-arranging example to say that such frivolities were not such things that Birkbeck University of London was providing courses for – rather it was/is providing for much more rigorous subjects and should not have its budget cut. It had its budget cut.

“Generally, part-time students at Birkbeck are not doing flower arranging. They are studying serious subjects I find it hard to believe that this is being done by good and decent people such as my right hon. Friend the Secretary of State for Innovation, Universities and Skills. He is my friend and he is honourable, but he is not right; he is wrong on this occasion. I cannot believe that Ministers have seriously considered the impact of this change on individual institutions.”

Frank Dobson MP, House of Commons, 08 Jan 2008

I can understand why Mr Dobson said what he said to John Denham (now at the University of Southampton), but it wasn’t comparing like with like. Birkbeck is essentially a lifelong institution that provides higher education courses that can lead onto degrees – and as an institution falls outside local council provision, whereas flower arranging is the sort of course you might find provided at a village school/college as an evening class – similar to what Sawston Village College south east of Cambridge, provides here.

Mr Shah’s introduction on breaking the stereotypes and the standard routes

One thing my generation of 1990s teenagers were not taught was ‘how to fail well’ – or ‘how to deal with failure’. I remember around a decade ago the artificial storm around modular exams and the ‘scandal’ of people being allowed multiple resits until they passed. At which point I wondered why the system was sending candidates into exams under-prepared. Cambridge town wartime swimmer and diarist Jack Overhill wrote extensively about his attempts to get a degree from the University of London through distance learning despite living in a slum and earning a living as a cobbler. I also lived the experience of going into an exam knowing I was not ready for it (A-level maths) feeling I needed another six months and/or different teachers.

“Imagine if you come from a disadvantaged background with parents with poor literacy, brought up in relative poverty suffering from hunger and so forth; and then hungry and sleepy at school you may be deemed stupid or disruptive by your teachers. These are hardly conditions conducive to be educated to take your legitimate place in society.”

Shah, Q (2020) Introduction

The concept of ‘a second chance’ was never discussed, never mind the prospects of those that ‘fell by the wayside’. And I remember using that term when, after graduating, trying to figure out what all those years in full time education was all for – and who it was for. Only at the time – and even now, it felt and feels like none of it was for me. Or us that went through it. On whose path were we on that others ‘fell by the wayside’?

The concept that institutions and their cultures might be part of the problem was never discussed. Collective support was never discussed. I remember that decade as one where ‘a culture of judgement’ pervaded. Whether it was on exam results to social and sexual morals. Have a browse of The Mirror and The People from the 1990s in the British Newspaper Archive and you’ll get some idea – especially the latter.

Mr Shah then describes his experiences as a teacher of lifelong learning. andbasic skills courses.

“I know of Adult Education’s life-transforming potential at first-hand having taught for the last 16 years in this sector, teaching Numeracy, ESOL and Literacy to the most marginalized of society’s individuals. I have witnessed the flourishing of people who had lost hope and confidence; women who thought of themselves only in terms of being housewives, subsuming their desires in favour of their families. Yet, within a short period of time and a little encouragement, they were writing poetry and plays: being inspired to look upon themselves as individuals with their own dreams and aspirations, and going on to mainstream education.”

Shah, Q (2020) Introduction

One of the problems with our present system is that it measures success primarily through exam results or progression onto employment.

“Yet others, the long-term unemployed, regained confidence through being in the classroom with others, forming friendships – feeling part of a community and society.”

Shah, Q (2020) Introduction

You cannot put a price or monetary value on that regained confidence. Or the creation of new, stable friendships. Or a sense of being part of a community and wider society. I’ve been on courses where I’ve passed exams and ticked a box, but certainly did not come out with any additional confidence, let. alone any sense that I was part of a wider learning community. On paper 15 years ago I was nominally that success story. But it was built on non-existent foundations and it all came crashing down.

On the importance of social contact

This links in with loneliness as a public policy issue, one that senior politicians all too often pay lip service to. Especially when there is a clash between a progressive social policy to combat loneliness in society vs a neo-liberal economic policy using a ‘stick’ approach to target those on the lowest incomes the hardest. This comes back to the different relationships with the state that different social classes have – in particular when it comes to housing (as I explored in this post).

If there’s one statement in Mr Shah’s paper that explains what has happened to adult education and lifelong learning provision in England since the early 1980s, it’s the above: “[From] Learning to be, to learning to be productive and employable“.

As Shah says, there is an extensive back catalogue of studies on lifelong learning that we’ve sadly forgotten (I’ve digitised some of my older copies here) that still read well today.

In particular Arthur Greenwood’s Education of the Citizen from 1920 – all the more important at the time given the enactment of the universal male franchise in 1918. Something that massively expanded the electorate at a time when compulsory primary education was less than 50 years old, and compulsory secondary education was still a dream.

Greenwood’s pamphlet was followed up in 1924 by the Church of England in a series of publication linked to their Birmingham gathering titled the Conference on Christian Politics, Economics and Citizenship. The reports are digitised here. One of them is on politics and citizenship.

You can read the above here – mindful of the social and political context of the first minority Labour Government under Ramsay Macdonald which took office only four months before – one that their Conservative opponents saw as an existential threat given. the Russian Revolution and the rise of communism after the First World War.

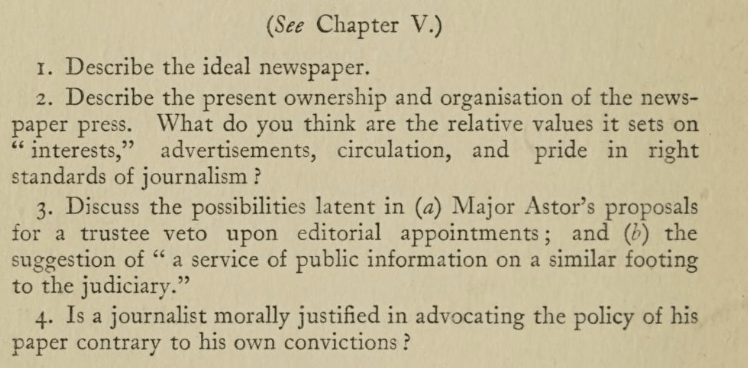

The section on political education (p30 here) is particularly interesting as the issues sound depressingly familiar despite the changes in technologies and social attitudes. Yet the publication also reflects the struggle that the Established Church had in coming to terms with this new era of mass representative politics and mass media. Furthermore, it carries a series of discussion questions – such as on the role of the print press below.

Above – COPEC Politics & Citizenship (1924), p8

One of the reasons these publications and the 1924 conference are interesting is because here was the church of state grappling with massive changes in society largely as a result of the First World War and the collective experiences of it. I get the sense that it was trying to reposition itself as a democratic anchor on top of how it saw itself as a a traditional civic anchor at a time when a new political force was in the process of suppressing the Established Church of the Tsars.

Lifelong learning centres as civic and democratic anchors

Fast forward to the 21st Century and following the decline the churches and trade unions compared with their 20thC predecessors, it’s worth asking what our civic and social anchor institutions are today. If we don’t have any, what are the new institutions that we need to form that can act as democratic anchors? All the more important in an era where the challenges are both global and *very fast moving*. (CV19, threats to digital communications infrastructure, pandemics in an era of integrated international trade and mass travel, to the climate emergency).

This bit is particularly interesting in an era where (in local government at least) hustings are few and far between.

“Moving on to abilities, inherent in being an active citizen is the act of engagement with one’s fellows. Consequently, it is important to develop abilities that promote association, communication, negotiation, collaboration and deliberation. Deliberation is essential as it ‘requires both voice and listening, both negotiation and compromise along with influencing others’, and ‘involves the testing of arguments for and against a course of action’.

“If we are to produce a politically literate citizenry who are resistant to manipulation, then some form of political literacy has to be taught to the population as a whole”

Shah (2020) p10-11

What’s striking is that lifelong learning centres are one of the few party-politically neutral institutions that also have the civic legitimacy to host such debates. (the Law requires it as a condition of either funding or charitable status) And yet over the past couple of generations we’ve seen the decline of those institutions. Therefore part of our democratic renewal and strengthening has to involve investment in lifelong learning institutions – existing and new.

What could these new/improved learning institutions be like?

I’d leave that up to local government institutions to decide. At the same time, history tells us of some very interesting examples they could learn from.

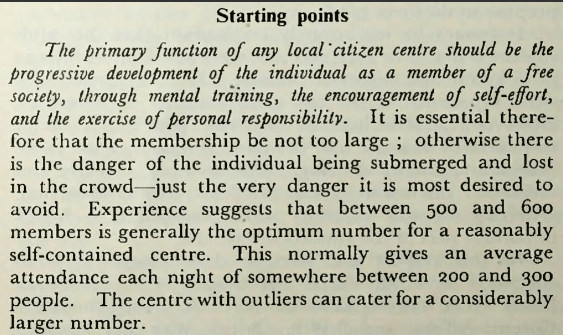

The first is this lovely pamphlet from 1944 on Citizen Centres for Adult Education, which Sir Richard Livingstone wrote the foreword for. Two paragraphs stand out for me regarding size, and culture. On size first:

And on culture:

Above – the ESA (1944) pages 11, & 13 respectively.

What’s really striking for me is seeing words from a previous generation stating what I had come to my own conclusions about – especially given the recommendation from the Education Select Committee in 2020 calling for a lifelong learning centre in every town. i.e Make them places where people ‘want to be’. That means no DWP sanctioning officers there, and it does mean having large open spaces nearby, and facilities such as a GP & walk-in clinic, dentist, and creche or nursery.

The study from the Workers’ Educational Association in Derby from 1968 which I featured here is one that still fascinates me. It outlines what an ideal lifelong learning institution might be like. What I really like about it is the proposal for it to function as a place where a host of different groups and organisations can make use of. In Cambridge today we don’t have anything like that sort of institution with that set up. We sort of used to with CCAT, but the reforms that broke it up in the 1980s and created Cambridge Regional College, and Anglia Poly-then-Ruskin University got rid of that ecosystem along with some catastrophic political decisions from Westminster alongside some not great business decisions that led to the demise of some of Cambridge’s largest employers that trained their staff there.

Finally, looking at the old Adult School Union

…which I wrote about here, I quite like the idea of what would essentially be a liberal arts annual course spending one morning/evening per week there. I wonder what the impact would be if employers decided to pay for their staff to do similar. i.e. saying ‘pick a course to exercise your mind, body, mental and/or physical skills.’ For example people in the sciences covering politics and economics, to people in office environments doing something practical involving applied engineering to ‘the things science has discovered since we left school’.

As with the Church Conference of 1924, the Adult School Union was formed along very strong religious lines, and so do allow for that context. At the same time, I like the concept of learning and education that does not have an exam at the end of tit – similar to what the U3A in Cambridge provide. Hence one of the challenges I’ve got is trying to bridge that gap between trying to design citizenship workshops and a course syllabus that meets the needs of the people of the city, vs the very slick, structured, and researched syllabuses of existing citizenship courses for children and teenagers (now around 20 years in existence) – ones. that have a back catalogue of teaching materials to use. I’m ignoring the Home Office’s publications because I think the institution should be abolished. That plus the handbooks they’ve produced are woeful and as such make the tests meaningless beyond the value that ministers place on them. (The content of new GCSE Citizenship textbooks for teenagers are far more substantial). Could they make a version that’s not focused on exams but remains accessible for the many?

I hope so.

Food for thought?

If you are interested in the longer term future of Cambridge, and on what happens at the local democracy meetings where decisions are made, feel free to:

- Follow me on Twitter

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge.