The Education Secretary hardly covered herself in glory with an off-the-cuff remark that reflected a lack of awareness on the impact of exam results in our teens. Why not listen to the teenagers and young adults themselves to suggest ideas for an overhaul?

Which then begs the question: Why bother with all those exams (and the huge industry of examinations that is behind it) if the ‘half life’ of qualifications is so short?

In the days of paper-based examinations, I remember pondering the environmental impact of everyone in the country having to do GCSEs like we were at the time in the mid-1990s. What happened to all of that paper? How much money did it cost to run the entire system? I also contrasted this with what became the annual “Exams are getting too easy” moans from various politicians and talking-heads from employers’ groups.

‘Lies, damned lies, and statistics’

Such as any minister who claims the country is spending more than ever on a particular public service without accounting for the population rises and demographic changes over time.

Listening to a couple of teenagers I’m acquainted with earlier on, they told me about the impact of the Government’s policy, and we (with their parents) discussed the various merits or otherwise of grade banding vs being assessed against an arbitrary standard. For example in a driving test, you have either displayed enough competence in the testable areas for the assessor to approve the granting of a full licence, or not. The ‘pass level’ doesn’t change depending on the number of people who have also passed their tests that year.

Psychologically what happens to us in our formative years does have a long term impact and can haunt some of us for years, decades after the event.

At the more extreme end, the academic research describes Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), and at the same time we also know from history that the abolition of the grammar school system across much of England was driven in part by the negative impacts that many adults felt on failing their 11+ exams.

“Those against grammar schools argue that they system is divisive and can have an adverse effect on those who fail an exam at the age of 11.”

ITV News 11 May 2018 Grammar Schools debate

I recall at the time at the tail end of John Major’s rotting Conservative Government in the mid-1990s what it would have been like if I had gone to a grammar school instead of a comprehensive where for my two favourite subjects (history and geography) we had mixed ability sets in which the latter involved going over year 8 content in years 10-11, only to be hit by second year undergraduate level content and standards when we got to year 12/lower sixth – only to drop back down again when I got to university!

Which is why I’ve never forgiven the Tories for the 1990s!

I also accept that it’s too late for me to change anything significant on that front, and that there’s also no point in trying to fight the battles of the 1990s in the 2020s in the face of huge social and technological change amongst other things. Hence looking at who is proposing which alternatives that might provide for:

- Better continuity for all, rather than the fragmented progression of the present

- A much broader base of activities and assessment methods that cover a multitude of talents and skills, rather than the artificially-restricted exams and coursework. (Thinking back to the Civil Service Fast Stream Assessment Centre I did in the mid-2000s).

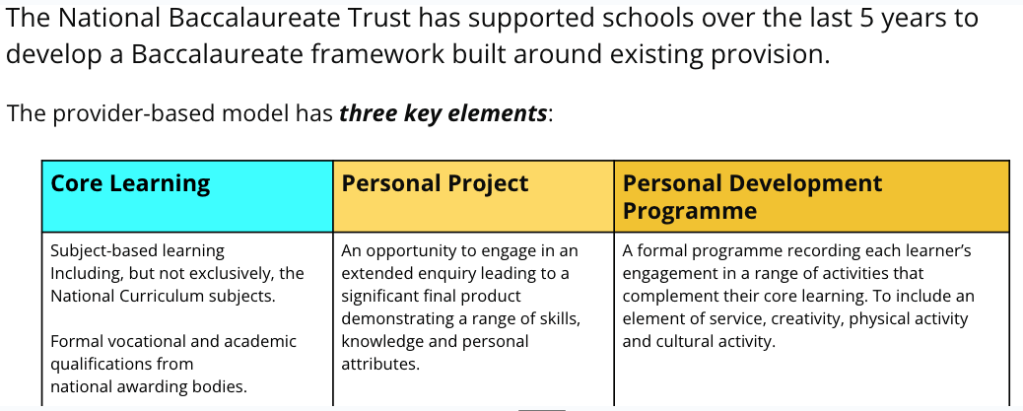

Hence I like the look of the proposals from The National Baccalaureate Trust. (You can read their summary here) What’s interesting about the model is that what are seen as the ‘all important extra curricular activities’ that are seldom formally assessed, are actually included in this system. Which means the state would have to fund those opportunities often seen advertised by private schools. That in itself would force some very difficult but much-needed public policy and political debates. Secondly it would enable more contextual information to be incorporated into the content of the BACC.

Above – from the slides from the NBT’s launch 22 Nov 2022

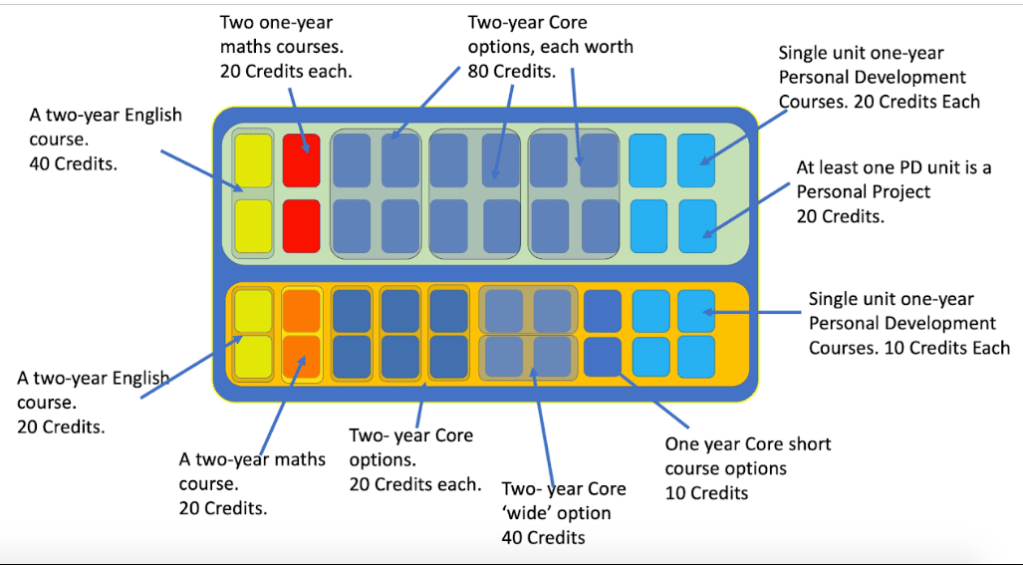

I also really like how it fits together and is more flexible in terms of how the credits add up, rather than having each subject as as a standalone subject.

Above – from the NBT’s proposals of March 2022, slides 9-11

In the two exemplars shown above, the top one demonstrates how the traditional GCSE/A-levels system would fit in, while the bottom one shows how an apprenticeship or a BTEC that’s the equivalent of three A-levels might fit in. One of the anecdotal reasons I have from the 1990s for the chronic skill shortages in engineering and the trades in the construction industry is the social culture that seemed to polarise us, leaving no room for the middle ground. Engineering was either portrayed as ‘very difficult extra maths and physics’ – which had the stigma of being a ‘swot’ attached to it, *or* it was seen as unskilled manual labour and not where ‘someone who did well at school but not too well so as to be a swot/teacher’s pet’ would go into.

Combine all of that with an overbearing exams culture and you end up with students all too often enduring a system that doesn’t allow them to follow their passions, but instead becomes a grind. Thus a combination of gaming the system and trying to get the maximum grade for the minimum of input/effort necessary becomes a matter for survival. Which is what happened with me in the subjects I ended up choosing.

Instead of an extended A-level geography project I did the statistics paper because it covered the content of the strand of A-level maths that I could do and also had a more competent teacher for. When it came to selecting modules for my final year at university, I selected two that I had covered in A-level economics. To both my horror and pleasant surprise, the standard and content was almost identical to the extent I was able to use my A-level revision notes from the late 1990s as the basis for my revision notes for my undergraduate finals. I had a sobering conversation with one of my lecturers after my finals at a social gathering she’d organised, and she asked me for my honest opinion about the past 3 years. I could see she was somewhat crestfallen by what I’d fed back, perhaps along with the recognition that the institution – like all of those before and after, never got the best out of me in my time there. 20 years later and I now know that this was most likely the result of undiagnosed ADHD or similar, alongside the inevitable failure of the institutions to make reasonable adjustments for it. And this feeds back into our system of politics and public policy, leading to this big picture question:

To what extent are our institutions and our national systems enabling people to meet their potential?

Amongst other things that means top-slicing oxbridge out of the equation. Not least because their structures, systems, processes, resources, and networks are ever so different to what most other higher education institutions in England have. That does not mean every student that gets into either Oxford or Cambridge has a splendid time and graduates with all of the splendidness you see in the photographs. A browse through Varsity shows that Cambridge certainly has a huge amount of chronic issues to resolve.

One of the shortcomings identified on pp5-6 of the NBT proposals is the failure to incorporate any acknowledgement of personal development and extra curricular activities. The subject-specific certificates can’t cover it as it’s outside their remit, so in that sense you’re dependent on a sound personal statement and reference. Yet when I look at the work the young musicians I’ve met over the years in the Cambridge local music scene – the most prominent of whom is Ellie Dixon having just returned from her first European tour nearly a decade after I saw her at a showcase for young musicians at The Junction, the system struggles to account for her musical talents. Not least because it’s still effectively paper-based. This is reflected in the slow and painful processes of trying to change party political campaigning alongside publicising public services. Actors, musicians, and professionals in the performing arts world have been making show reels for decades. A series of short clips showcasing their work. Trying to persuade politicians to do this? It has been a struggle! But when you’ve been institutionalised by a system that has made you successful and which you have been successful within, it’s not always easy to spot its shortcomings. Which is why diversity not just of backgrounds but of life experiences is ever so important in political. and public policy institutions.

And on that we’ve still got a very long way to go.

Food for thought?

If you are interested in the longer term future of Cambridge, and on what happens at the local democracy meetings where decisions are made, feel free to:

- Follow me on Twitter

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge.