The Chief Scientific Adviser at the Department for Transport delivered a timely presentation for the annual Cleevely Lecture at Peterhouse, Cambridge.

This was the first public lecture I had been to for a long time, and unlike previous ones, I didn’t live -tweet it. Instead I wrote down notes on a blank piece of A4 card as Prof Sarah Sharples of the University of Nottingham took the audience on a crash course in the future of transport – a decarbonised one.

The annual Cleevely Lecture was founded a couple of years ago by Dr David Cleevely CBE – a number of readers of whom will be acquainted with, and someone who has supported me in projects past. It was that guidance on how to put together project proposals that you want others to support, that I was able to pass onto younger generations when working with them on their own college-related projects – something that participants were able to use for job applications and in real world scenarios.

My big ‘takeaway’ from Prof Sharples talk was on how the City of Cambridge is getting its systems thinking all wrong – not just in the field of transport but on a host of other areas. Given my own public policy background, I was struck by how little interaction there was between higher education research units and public policy teams inside the civil service. It will be interesting to see to what extent the next government pivots away from partisan think tanks and towards university-based institutions. That’s not to say the latter should be given a free pass – rather that it’s a chance for such institutions that receive public money to demonstrate the high calibre of their applied public policy research.

There were a few things I would have liked Prof Sharples to have addressed, but given she said there was a huge amount of content that ended up on the cutting room floor, it was understandable that she kept her focus to her top five big challenges. Transport policy is a field where it is *very easy* to get side-tracked. Furthermore, the one issue I would have been interested for her thoughts on was not something that has a scientific answer. That issue was what the most suitable governance structure for local and regional governance is to deliver a decarbonised transport system. That ultimately is a political decision because it inevitably involves having to make the case to the electorate. What the electorate might want is not necessarily the structure that makes for the easiest means of delivering that decarbonised transport system – as the Committee on Management of Local Government found out in the mid-1960s when the direction of policy was to reduce the number of small rural and urban district councils. (People distrusted more remote institutions).

‘Wicked problems‘

You can find a range of definitions to what the above is, but for the purposes of the lecture, Prof Sharples top three features of them included:

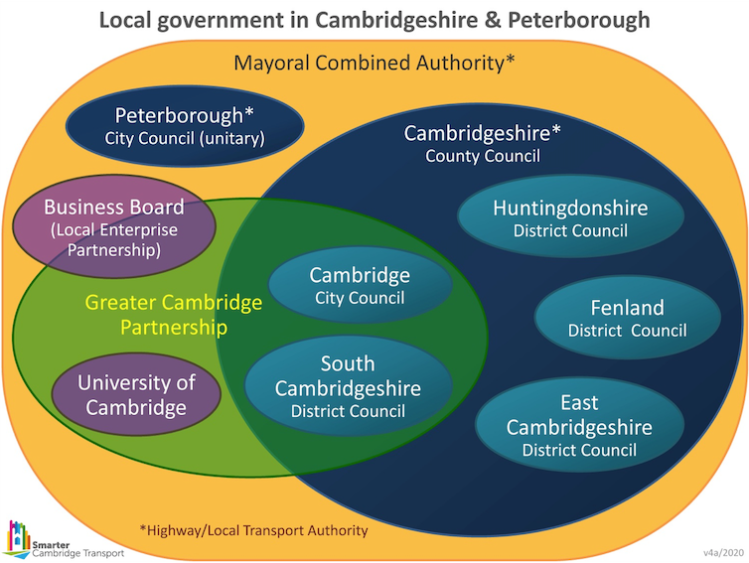

- Complexity – for example atmospheric systems by their very nature are inherently complex. The structures of local government in and around Cambridge on the other hand are unnecessarily complicated – and can be simplified (if there is the political will!)

- Contradictory – for example having to expend energy on something in order to reduce the consumption of it, appears at first hand to be contradictory

- Changing – look at the changing habits of transport users in Cambridge over the past decade. When the GCP was established, hardly anyone was going around town on e-scooters. Today? The failure to prioritise and allocate far greater amounts of funding towards segregated cycleways (rather spending fortunes on consultants on busway plans that have not yet commenced) is one illustration of the GCP failing to adapt to changing transport habits.

The top five challenges arising from the process of decarbonising transport?

- Moving from physical to digital – and not having the latter as an afterthought;

- The Ironies of automation – such as the risk of losing skills and collective knowledge as society adopts new technologies

- The Energy Enigma – using energy for decarbonising transport, such as extracting rare earths (and all the geo-political risks to mitigate with that)

- Safety – not just ensuring that the technlogy is safe, but also convincing the public that it is safe and/or the right thing to do (Thinking Barbara Castle as Minister of Transport bringing in seatbelts and breathalysers)

- Consent – taking the people with us – the Greater Cambridge Partnership being a case study in how not to do this.

I raised that final point with Prof Sharples in the Q&A session highlighting there were a range of things in her talk I’d like to learn more about, but without a lifelong learning college in Cambridge accessible to people on low incomes, my options are very limited. I also mentioned that public transport isn’t mentioned at all in the GCSE Citizenship Studies syllabus, & mentioned how the recent local election results had hit the GCP (and the political consensus in it) like a thunderbolt.

Science and public engagement – ditto engineering, technology, maths and even public health

Even though overhauling Cambridge’s transport system is a devilishly complex task – one whose history has been littered with failure (see my Lost Cambridge blog for case studies), one of the things that has been missing is that ecosystem of community learning over the longer term. This is an issue that goes far beyond the responsibilities of a departmental chief scientific adviser, and is ultimately one that would require agreement between ministers from different departments to deal with. Which reminds me of my civil service days being a project officer for a project board that had representatives from ten Whitehall departments. It was like herding cats. Or dragons.

“Bernard, what happens if it becomes apparent that a new transport system needs to be built in a city like…Nottingham. (Or Cambridge) …and there are rival proposals for what should be included in it?”

Above – Sir Bernard describing part of my civil service career when I was working on local government reform in the mid-2000s

“Well we set up an interdepartmental committee, Dept for health, Dept for Education, Dept. forTransport, HM Treasury, Department for the Environment, ask for papers, hold meetings, propose, discuss, revise, redraft – that sort of thing!”

Yes Minister – British Democracy clip, BBC Studios

Yet when we look at the proposals from six council leaders from Labour-led councils that were published by the New Local think tank very recently, we find a familiar call for local councils to take control (or at least have some oversight) over public services that traditionally look upwards or London-wards as to where they get their orders from. This includes NHS services, Job Centre Plus, and even schools with the new Regional Education Commissioners. Furthermore, even though adult education budgets have been shifted to combined authorities, the legal powers for establishing and providing funding for new lifelong learning colleges rests with ministers, as the now Education Secretary Gillian Keegan informed Cambridge MP Daniel Zeichner when the latter wrote to ministers on my behalf.

The Combined Authority’s limited programme for lifelong learning reflects the Government’s priorities on jobs-based training on functional and basic skills for the workplace, along with providing the minimal level of funding necessary to deliver it

This means it is harder to justify funding courses that have indirect benefits. Furthermore, it is even harder to innovate in the field because very few are willing and able propose new courses because of the huge financial risks. For example take a one year GCSE Citizenship course that is applied to mature learners. A potential tutor has to prepare:

- a business case to the host institution on why they should fund such a course *and* provide the premises and facilities for it to take place in

- an annual scheme of work for the course

- individual lesson plans for three terms

- an evaluation plan demonstrating how learning will be monitored to ensure that course participants are learning what they should be in order to get the highest possible exam result.

All of the above has to be done before you can think about getting your first pay packed. Furthermore you will need to have completed basic teacher training in the lifelong learning sector (the old PTTLS course that I took at CRC) before you can be employed by a college accredited with the Department for Education.

As I mentioned, the main providers in Cambridge (Adult Learn & Train by Parkside, and Hills Road Adult Education alongside Cambridge Community Arts) have had to cut back on what they can offer. Yet given that loneliness in society is such a chronic issue – to the extent there is a ministerial portfolio for it, are those cuts false economies? Are there non-financial dynamic gains from increasing funding? Especially for those subjects and issues that involve people discussing and debating things?

This was where Prof Sharples acknowledged her academic community in engineering has a very real challenge. If decision-makers at whatever level are to take the people with them – i.e. have their consent to make what will be massive changes to our built environment, then learning and education has to be part of that process. The problem in Cambridge is that even when academically qualified people have challenged decision-makers such as the GCP on their proposals, their concerns have been dismissed in such a manner and such a frequency that ultimately a critical mass of the public delivered a set of election results in May and June 2023 that seems to have broken the long term party political consensus that was essential to the functioning of the GCP.

We find out at Thursday’s GCP Board Meeting (See the papers here) whether the trio of voting members will go for broke and put the C-charging proposals in front of county councillors (who will surely vote the proposals down) or whether they concede defeat and go back to the drawing board. The root of the problem – as I have written on many occasions, is *not* a transport problem. It is a Political one because it is a financial one.

The GCP papers have repeatedly said the aim is to come up with an independent revenue stream to subsidise buses, and that this or a workplace parking levy (allegedly vetoed by the University of Cambridge / Cambridge Ahead / depending who you believe) are the only legal options on the table. No one within GCP/CPCA circles seems to have gone back to Ministers to make the case for alternative local revenue-raising or funding systems even though this is something MPs have already demanded.

As Prof Sharples said at the start of her talk when recalling what to do with ministers disagree with what she has recommended:

“Advisers advise, ministers decide”

Which is how it should be. In the case of sustainable local council funding (and thus local transport funding), the advisers in Parliament at least, have advised. The decision by ministers to carry on with austerity is a Political decision. One that has led to Birmingham’ financial troubles. If MPs in the present parliament cannot persuade ministers to change their policies, then it looks like the responsibility will move to the electorate in a very broken electoral system to elect a new generation of MPs (from which new ministers can be drawn from) to bring in a more sustainable system. And that’s not something that can be taken as a given, whoever wins the next general election.

In the meantime, we wait for Michael Gove’s next move.

If you are interested in the longer term future of Cambridge, and on what happens at the local democracy meetings where decisions are made, feel free to:

- Follow me on Twitter

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge.