It’s a policy most senior politicians would not dare touch because to goes counter to the mainstream mindsets and could set precedents that would be difficult to deal with in other sectors. But something has got to give.

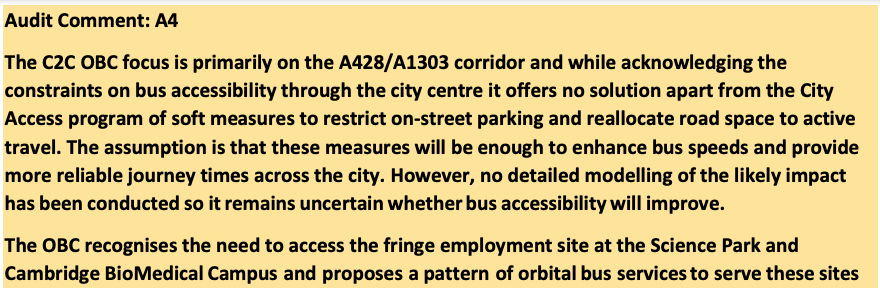

This follows on from a point made by Prof Sarah Sharples of the University of Nottingham, and the Chief Scientific Adviser to the Department for Transport at the Cleevely Lecture in Cambridge. (See my write-up here). Her premise was that in imagining what transport will look like and be like in 2050, we have to examine *how* we get there in terms of public policy changes and also changes to our built environment. That means thinking about transport as an integrated system rather than as A-to-B corridors that the Greater Cambridge Partnership’s officers and technical advisers have done with their busways proposals. They were called out on this by independent auditors back in May 2021, and even now the GCP still has no comprehensive response to the challenge from that assessment.

The line that the Transport Director of the GCP Peter Blake has consistently responded with is that the buses would join the existing bus network. This is where the lack of systems thinking breaks down. The structures mean that the running of the existing bus network is not the Transport Director’s problem. That’s a Stagecoach issue. And when we look at their provision of bus services, same problem, different year – as the front page of the Cambridge Independent of 27 Sept 2023 demonstrates.

Last year, the Mayor of the Combined Authority had little choice but to bring in a bus precept to fund replacement services which Stagecoach decided it no longer wanted to provide. Thus we are stuck with a system that prioritises corporate desires of private firms and not the economic, social, and environmental needs of the county.

The failure of an ideology

Let’s be clear: This is not the fault of the Transport Director. This failure has its roots in the privatisation of the buses in the 1980s. Note it’s surprisingly difficult to find books that cover the history of bus privatisation – which makes scrutiny of current transport plans that much harder. Ultimately:

The buck stops with ministers.

They are the ones insisting on a convoluted bus franchising process with multiple steps that require ministerial approval – a symptom of our over-centralised system of governance in the UK.

“Blobs”

When it comes to ‘blobs’ that Gove and others like to talk about, all too often it is their own political party in government that forms the blockage – either by their refusal to move on important issues such as the climate emergency, or their refusal to change systems and structures to give devolved administrations and local councils in England more freedom to operate (including revenue-raising) without constantly having to get ministerial approval. (One example is the system of competitive funding pots)

“Where will the new bus drivers come from?”

This is one of the issues that was raised when inflation rose to recent historical highs, and the cost of living crisis kicked in to such an extent that more than a few bus drivers moved to the freight sector which started paying more. Bus drivers have told me in the past that while Stagecoach has a good training scheme, their pay for experienced bus drivers remains low. The inability of councils to raise revenue via a wider range of progressive taxes and levies means that the system of local public transport is unable to raise revenue to pay the bus drivers more. Furthermore, the recent local elections have told us that the public do not trust national or local government’s promises of better services in return for congestion or road user charging. (Note the recommendations from the Transport Select Committee on road pricing in this LGA paper). Again, we come back to the issues raised by Prof Sharples about ‘bringing the people with us’ – and having the alternatives in place such as light rail.

The point about the bus driver shortage however, reflects a wider problem. In a cost of living crisis where high rents and high food prices mean long hours, where are workers who would like to switch careers meant to find the time to retrain?

A world where the workforce is expected to retrain in a new profession every generation is unsustainable in our current system

This is because it is the workers that bear the greatest financial costs of retraining – whether in loans or relying on another person eg family member to bear the burden of their living costs while they retrain. And that’s before we’ve even mentioned tuition fees.

One reason why senior politicians of the major parties won’t touch this issue in a meaningful way is because it shreds the political principles behind the system of higher education fees that all of them voted for at various points since the late 1990s – my generation of A-level leavers being the first to be hit by it. (I still feel the ‘injustice’ that my older brother got a grant whereas my generation didn’t!)

It is, as Prof Sharples pointed out, a wicked problem:

- Complex

- Contradictory

- Changing

Taking each point at a time, higher education funding policy is complex by its very nature – not least because of the numbers of people, academic disciplines, and institutions involved. It can be contradictory because some of the spending will be directed towards people who are from affluent backgrounds and professions which seems to go against progressive principles of redistribution.

Another example is some of the spending will go on training professionals who will end up working in professions that work against the public good – whether those who go on to work in the fields of fossil fuel exploration to those working in professions that capture and extract the commonweal for private gain for a very wealthy few. And finally it is forever changing – what might be a workforce or public policy priority today may not be those of decades into the future. Think of all of those engineers trained up to operate steam engines and locomotives on the railways until the widespread introduction of diesel engines. And then if/when more of the railways are electrified, will that demand move away from skilled diesel engineers towards engineers skilled in large electrical engines? Again, Prof Sharples made this point.

Shortage of planners – what would the impact be if ministers provided funding for a substantial number of scholarships for older learners covering fees and subsistence to enable people to undertake town planning masters degrees?

“A quarter of planners left the public sector between 2013 and 2020. Meanwhile, the private sector experienced an 80% increase in the number of employed planners, according to today’s analysis from the Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI).”

RTPI 16 May 2023

Ministers have shown little appetite to reversing austerity in local government or making meaningful changes and improvements to the structure of governance structures in England. See Michael Gove here.

Above – it’s not like the sector hasn’t faced challenges before (See Redcliffe Maud’s assessment on the alternative reforms of 1974 – different to the one he proposed in 1969).

Again, the complexity of the challenge arises because in somewhere like Cambridge the demand for town planners is acute. That demand however won’t be uniform across the country. At the same time they will have their own area-specific shortages, making. the micromanagement of who gets what funding for which sector extremely difficult to manage from an office in Whitehall. (Trust me, I’ve tried it (as part of a very policy talented team, but even we couldn’t crack it), and wouldn’t wish it on anyone!)

Could a revamp of local government in England enable the co-ordination of such scholarships/grants to be directed towards those sectors where both the needs and opportunities are the greatest?

It could, but it’s not without its pitfalls. One of the essential components is robust and accurate data that is routinely refreshed to reflect changing economic need. Another is acting on the principles of what the New Local thinktank published on behalf of six Labour councillors on Community power: prevention. What are the skills needed in which areas of the country (and which jobs need to be funded to do the work) to ensure that demand say for health services to treat symptoms later on down the line, is actually reduced?

Mental ill-health is a classic case. The system incentivises patients to become more ill because the rationing of scant resources mean that only the most ill get any treatment. Therefore anyone who is moderately ill and who wants and needs treatment has the contradictory incentive to get *more ill* before they can get better. Despite being told this for years if not longer, ministers still have not made the policy or funding changes to put an end to this situation. This is not the fault of the patients or of the healthcare staff. This is a Political issue and ministers past & present are responsible.

A contemporary example of where advice is not enough

Again, this is not the fault of Form the Future – who do great things in and around Cambridge. Supporting single parents isn’t simply a case of ‘providing advice’. What are the support systems in place? What’s missing? Given the age range (under-24s), what was their experience of school like? What things need to be avoided/accounted for? This is why I think new lifelong learning centres should be designed in a way *that does not look like a typical school*.

Above – financial support is conspicuous by its absence, as is transport access.

Again, this reflects ministerial priorities.

What the priorities of ministers in a future government will be remains to be seen. But like many, I’m getting tired of waiting for things to improve, having more than exhausted myself against the blob that seems be doing little more than passing time in power (and/or making things as difficult as possible for whichever party forms the next government).

It’s like 1996/97 all over again.

Food for thought?

If you are interested in the longer term future of Cambridge, and on what happens at the local democracy meetings where decisions are made, feel free to:

- Follow me on Twitter

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge.