The Cambridge and County Folk Museum quotation applies again: From Papua to Pampisford. Can Cambridge University’s researchers apply the lessons from their research for the improvement of city, district, county, and sub-region?

That was the challenge from former Councillor Sam Davies MBE – whose vacancy is now up for grabs in Queen Edith’s.

You can read the report on Bristol here.

The top themes they found were:

- Longevity: “…importance of not just having a long-term approach, but also having an organisation that is able stand the test of time”

- Partnership rooted in place: “…all have understood the important role that culture can play in making Bristol both an economically and socially vibrant city from the outset.”

- A broad definition of culture: “…moving beyond ideas such as ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture and a division between the arts and science”

- Assets of place – including its past: “… the history of Bristol itself, which has been used as a way of both convening people and communities around the commemoration of events in the long civic life of the city”

- Measurement: “…it is through understanding the role that culture can play in creating a sense of civic engagement and contributing to the social capital of a place, that we can really understand its value.”

“How do we apply all of the above to somewhere like Cambridge?”

I’m going for a different approach – a very subjective approach based on my experience of growing up in Cambridge during the 1980s and 1990s, comparing this and the Cambridge of today to the concepts listed above.

Before we begin, have a look at the key stats on Bristol – because as a city it has a very different history to that of Cambridge. Furthermore, the cities today are very different in size – Bristol City Council being responsible for nearly 500,000 residents, while for Cambridge it’s closer to 150,000. Bristol has four MPs covering the wards within the city council boundaries, Cambridge has two, with one of those two currently only covering one ward (soon to be two). Bristol is a unitary council, Cambridge is a two-tier council – the latter with far fewer powers and finances to do anything substantial in our city.

What I’m not going to do is to give a piece-by-piece review of the Bristol Report. That piece stands alone and is worth reading as is, rather than ‘within the context of another city’ whether Cambridge, London, or anywhere else. I’m interested in how the five themes that emerged from the report could apply to Cambridge – as Sam Davies mentioned.

“Bring your ideas” – we did, and were ignored.

Have a look at the open by Caleb Parkin on p4 of the Bristol report

…and then ask yourselves if ministers, councillors past and present on the Greater Cambridge Partnership, and senior decision-makers within the Cambridge University bubble along with other wealthy and influential interests over the years have demonstrated putting into action the ideas that the people of our city have brought forward.

“let your ideas stop the bus until injustice gets off

Caleb Parkin, Bristol Report (2023) p5

let them magic lantern Liberty from Fishponds to the Docks

let’s talk ideas across borders, over trenches

make them supersonic fledglings”

The top two lines are very specific to Bristol’s history as a slave trading port – one where much of its historical wealth was made. One of the reasons I think that the city was able to withstand the party political, and print press firestorm over the hauling down of the statue of slave trader Edward Colston was that a critical mass of the people of Bristol had a strong enough understanding of their city’s history that they had the self-confidence to tell the print press and the politicians where to go. And a fair amount of that can be credited to the Radical Bristol History Group.

Sadly for Cambridge, we don’t have anything like that to sustain a radical historical tradition even though at various points in our civic history we can point to events and incidents where local people kicked sand in the face of the local ruling class – whether town (Mortlock and chums) or gown. After all, the City of Cambridge cannot pretend it has a clean record on slavery when the borough Tories decided former slave owner Sir Alexander Grant would make for a splendid Member of Parliament for Cambridge Borough in 1840, and promptly plonked him in the seat – despite anti-slavery protesters gatecrashing his speech on Parker’s Piece.

“Does Cambridge have a civic-minded institution that is energised, has widespread consent from the people of our city, and is well-resourced and independent enough to stand the test of time?”

No.

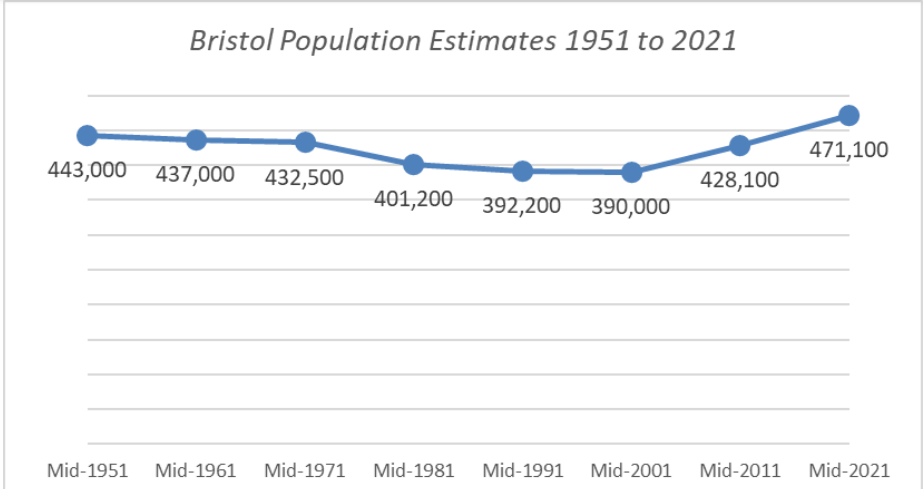

Again, we must be mindful of direct comparisons with Bristol – not least because if you look at the Joint Strategic Needs Assessment for Bristol, the population since 1951 has shown a fall, then a rise – the current population being less than 10% higher than what it was when King George VI was on the throne.

Above – from Bristol JSNA 2021, p2

In the same year (1951), Cambridge’s population was measured at 81,000. Add another 70,000 people to that total and you get closer to today’s population. By the time of the next census chances are the population will be almost double the 1951 figure. Combine that with the polarised society of town vs gown, and you begin to understand why Cambridge’s town history has been the poorer relation when it comes to resources. Our city and district local history society is one structured for a large market town – one with strong links to a number of local village history societies in the surrounding area. The Museum of Cambridge is not based in a grand civic building – whether a bespoke one or a renovated old one that had a previous use.

“Rooted in ‘place’ using assets of the past’?”

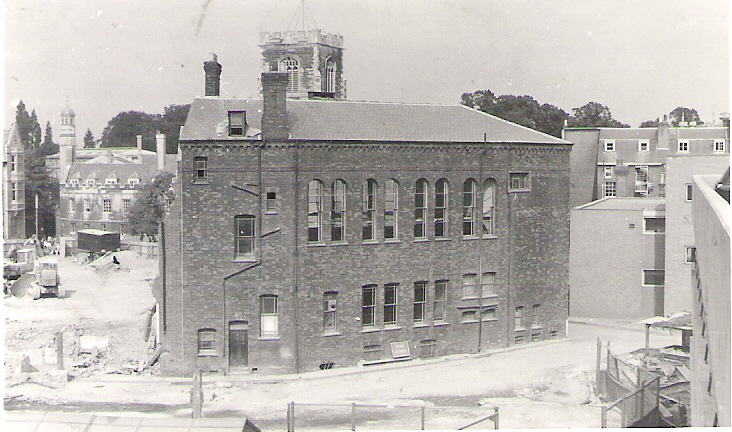

Sadly Cambridge fails on that one too – having had demolished too many of its former civic and social buildings of note.

Above – clockwise from top-left: 1) Norwich Union on the corner of Downing Street where John Lewis now is, the old Fosters Mill that Brookgate was unable to protect from arson, 3) the old YMCA. /Alexandra Hall of 1870 – awaiting demolition circa 1970, 4) the old Cambridgeshire Regiment Drill Hall on East Road, now a faceless office block), and 5) the old Cambridge & District Co-op HQ on Burleigh Street, now Primark.

So no, Cambridge the town historically has not been able to use the assets of its past – for a mix of political decisions, and those taken by big institutions – not just the University of Cambridge and its colleges, but financial institutions such as Norwich Union.

“Wasn’t partnership working meant to be all the rage some years ago?”

Apparently, but just as I haven’t seen the results of it in recent years except in affluent circles, I seldom saw many examples of it growing up in Cambridge – where town teenagers were about as welcome as The Plague as far as the University of Cambridge was concerned. I cannot tell you how utterly soul-destroying it is to see the same thing happening again with today’s generation of teenagers and young people – only for them it is even worse. Furthermore, the inequalities are so entrenched they are advertised on the buses in the form of adverts for private schools. How sickening it must be for families living in council and social housing who are dependent on bus transport to have the images of plush private schools and colleges shoved in their faces every time a bus drives around.

But then there are more than a few people and organisations who have strong financial incentives to promote the ‘exclusiveness’ of Cambridge instead of a vision of an inclusive city. “One Cambridge Fair For All” is the slogan of the Cambridge Labour Party. As the party in control of Cambridge City Council, this was incorporated into the latter’s corporate plan 2022-27. With the existing fragmented picture of local public services in and around Cambridge, and the lack of powers to tax the wealth being made here, I struggle to see how such a noble ambition can actually be achieved within the existing structures and systems. Hence why I believe general election candidates across the four constituencies in and around our city (mentioned in my previous blogpost) should state how their party if elected to national government will change the law and change the structures of how Cambridge & Cambridgeshire are governed.

There was very little convening of people and communities in 1990s Cambridge – especially if you lived in an area that was poorly connected to the wider city.

I’ve said this many times to Cambridge Labour activists, but had they got hold of me in the early-mid-1990s I would have been flying around South Cambridge campaigning to beat the political living daylights out of the Tories – who going by my manuscript diaries of the era I utterly despised. When you had Cabinet Ministers making speeches like this, you can see why. Note mine was a generation that spent many-a-lesson in mobile/temporary classrooms. A curse the Conservatives of 2010-23 have imposed on yet another generation of children. And yet given the wealth Cambridge supposedly makes, why are our systems of governance unable to allocate any of that wealth to meet the needs of the children and teenagers? Who designed the structures that stop this from happening? Who is keeping them in place? Charity is definitely not the answer.

High brow and low brow culture

This is something I really feel strongly about because the social divisions were ever so apparent even at the time in the 1980s and 1990s. Working class boys played football and used bad language, middle class boys did their violin practice and went to church. And didn’t swear. I conformed to the latter even though at the time all I wanted to do was to play football like most of the other boys. But I wasn’t good enough for any of the organised leagues Note in those days girls didn’t get to play football – there was no one around to organise it for them.

So those of us ignored or cast aside by the adults did things for ourselves. Sometimes we would go onto school playing fields because they were safer than parks and because the Tories had underfunded the schools so much that they could not afford to build the security fences since erected to stop us from getting in. Note this was a generation where the children and their families could not afford the consoles and computers that were all the rage.

On the class divides, I remember getting the firm impression. that the violin was for Vivaldi, and that singing was for choral music’ in churches.’ There was no culture of breaking out of those barriers *unless* you had an adult within your family’s social circle that had the knowledge and connections to enable you to do so. This was the case with drama and music groups outside of classical music in particular. Furthermore, the classical music concerts that were targeted at children all too often involved the inevitable dress codes which for boys meant itchy wool/nylon-blend trousers on uncomfortable seats at West Road Concert Hall that no car parking and no bus transport. With the building of new high quality performance venues at The Perse and The Leys private schools, there’s an understandable desire for performing groups to want to perform there. But the location and lack of public transport means it’s not easy for people from less affluent parts of our city to get there and back. Hence my case for a new North Cambridge Arts Centre.

The artificial ‘Arts vs Science’ cultural divide

If a chief scientific adviser to a Government Department doesn’t have the solution on how to bridge this gap at a city/lifelong learning level, what hope is there for the rest of us?

“[I said to Prof Sarah Sharples] there were a range of things in her talk I’d like to learn more about, but without a lifelong learning college in Cambridge accessible to people on low incomes, my options are very limited.”

Q to the Chief Scientific Adviser to the Dept for Transport, Cambridge 26, Sept 2023

At the age of 16, the woefully-inadequate careers advice service in Cambridgeshire told us teenagers that we had to decide between an arts/humanities stream or a scientific stream for our A-levels. One of the few ways to keep your options open was to study geography and maths, plus one other subject. Which is what I did. That choice along with a culture of ‘you’ve made your bed’ (i.e. you were not meant to try and switch because of all of the fuss it would cause) meant I was locked into that stream until I graduated some six/seven years later. In between the lines of my point to Prof Sharples was that no one could expect society to adapt to new technologies and the challenges of a climate emergency if ministers refused to provide funding for, and make the policies for the learning and education required for this.

“So…to conclude?”

Those that might have the power and/or influence to change the structures and systems are either too comfortable with those existing structures and systems to want to change them in any radical sense, *or* they/their institutions lack the instinctive curiosity to venture outside of their own sectors/bubbles to see what’s happening in places and communities that they would not normally spend time in. (And/or something else – just throwing that one out there so I don’t get sued).

In the 1990s I definitely fell into the trap of the latter – losing any instinctive curiosity to spend time north of the river. I was all too willing to believe the negative rumours of places like Arbury – until as a teenager in the summer holidays of Year 12 I found my desire to earn more money (£2.65 p/h in those days) stronger than my fear when me and a group of us wanting additional hours at our local small supermarket were told Arbury was the only place available – and they were so desperate you could have as many hours as you liked. So off we went.

Who in the affluent, influencing social classes in/around Cambridge who is not necessarily involved in political debate has the personal and intellectual curiosity to explore, find out about, and listen to people in communities that they don’t get to engage with on a regular basis? What would be the impact of a critical mass of people from those backgrounds. and professions undertaking some actions in a transparent but low-profile manner. i.e. working with existing communities, not going in there and spying on them. As Sam Davies can tell you, simply taking the names on the door at one of our city’s food hubs even for just one morning can give you the sort of snapshot of the state of our city that academic and corporate research studies struggle to capture.

Which brings us back to the link to “Bristol Ideas”

Cambridge has its own ideas festival. Or rather it did until it was rebranded the Cambridge Festival. We used to have an arts/music related one in the olden days but that demised in the 1990s following the retiring of the main organiser.

Above – logo of the old Cambridge Festival for the year 1986 – British Newspaper Archive

Is there any point in trying to come up with something that Bristol has been successful at creating when Cambridge’s institutions don’t seem to show the inclination, curiosity, or desire not only to engage and listen to the ideas of its residents – especially those are all too easily over-looked, but to turn their ideas into something inspiring and long-lasting?

Just as we need to get the basics right on things like potholes if we are to debate active travel and light rail ideas, institutions and influencers need to make their own changes if Cambridge is to become a city greaater than the sum of its parts. Sadly at the moment, it cannot even do the basic additions.

Food. forthought?

If you are interested in the longer term future of Cambridge, and on what happens at the local democracy meetings where decisions are made, feel free to:

- Follow me on Twitter

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small subscription or donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge.