Another day, and another article making a case for the growth of Cambridge. Only this one is heavily caveated in ways that headlines cannot reflect

This is from a follow-up article by Oxford economics researcher Ben Ramanauskas, formerly of the Taxpayers’ Alliance and also adviser to Liz Truss when she was Trade Secretary under Boris Johnson.

“Ben Ramanauskas contributes another perspective on this important debate, arguing the case for further agglomeration in and around the city.”

Bennett Institute 2023

The first thing I always look for in any economics-based argument are the assumptions. In part because during my own undergraduate years studying the subject over 2 decades ago, the models we were presented with all fell down one way or another on their assumptions – very strong ones that when tested in the real world were found to be wanting. That plus the authors of core text books and articles doing things like recommending voting for George W. Bush at US presidential elections to not declaring which Icelandic banks were paying them to write puff pieces about the Icelandic banking system prior to its implosion in the Banking Crash only reinforced my scepticism in the years that followed.

“...as long as impacts on the environment, infrastructure, and the surrounding area are given serious consideration, [my emphasis] then turning Cambridge into Europe’s Silicon Valley is a necessity for the city…”

Ramanauskas in Bennett Inst. Nov 2023

What might be seen as a ‘routine caveat’ for Mr Ramanauskas is anything but for those of us that have lived through the past decade of meetings, campaigns, and elections that have involved policies and projects of the Greater Cambridge Partnership. My civil service training means I also look at the structures, systems and processes of whatever is proposed to achieve said objective, and ask how those things can possibly go wrong. Because in the case of the Greater Cambridge Partnership, signed off in a wave of publicity with the Cambridge City Deal in 2014, things have most definitely gone wrong.

Mr Ramanauskas needs to analyse the institutional and governance structures involved with proposals to turn Cambridge into, well, anything – Europe’s Silicon Valley or otherwise.

I’ve been working on the basis that Cambridge is going to continue growing in the existing system unless and until something related to the climate emergency hits us. Having spent most of my life living in Cambridge, I’ve seen the city grow from a population of under 100,000 people to over 150,000 within my lifetime. I’ve lived that 50% expansion of our population – a population within our 1935-era boundaries. (That was the last time national government enabled the extension of the municipal boundaries). Not that others tried.

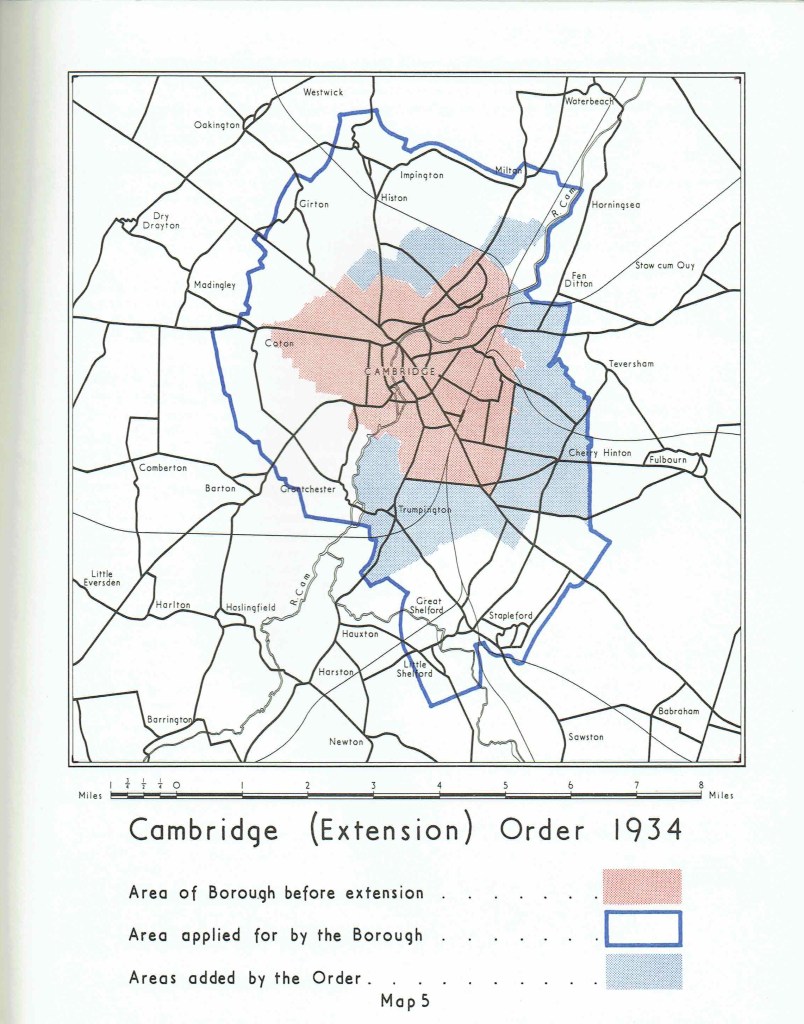

Above-Left, proposals for a Cambridge Unitary (with a Peterborough Unitary to the north) proposed by Lord Redcliffe Maud’s Royal Commission in 1969 – adopted by Harold Wilson but scrapped by Sir Edward Heath’s Government. Above-Right, what the boundary changes gave Cambridge vs what the old Cambridge Borough Council applied for.

The Cambridge (Extension) Order 1934 was an interesting discussion point for all of the groups that took part in my recent introduction sessions of the Great Cambridge Crash Course (see future events here). The big learning point from the discussions of early 20thC town history was that Cambridge’s municipal boundaries are not set in stone, and that the process of changing/extending them involves Ministers and Parliament.

The current generation of pro-big-expansion-of-Cambridge campaigners are not the first.

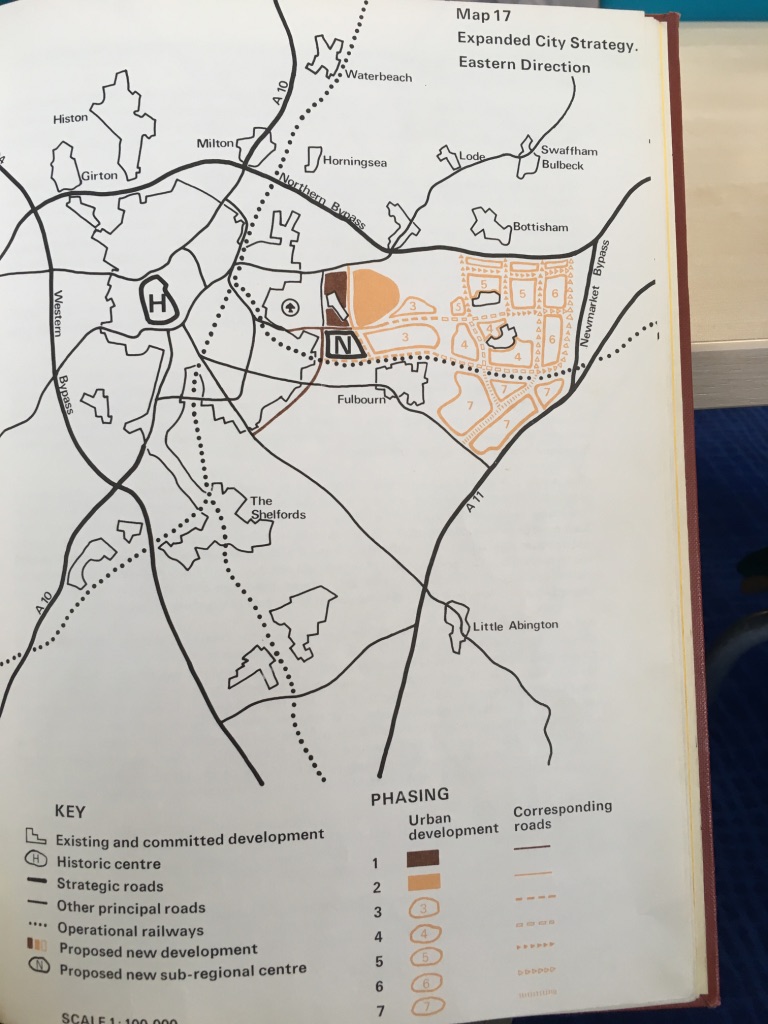

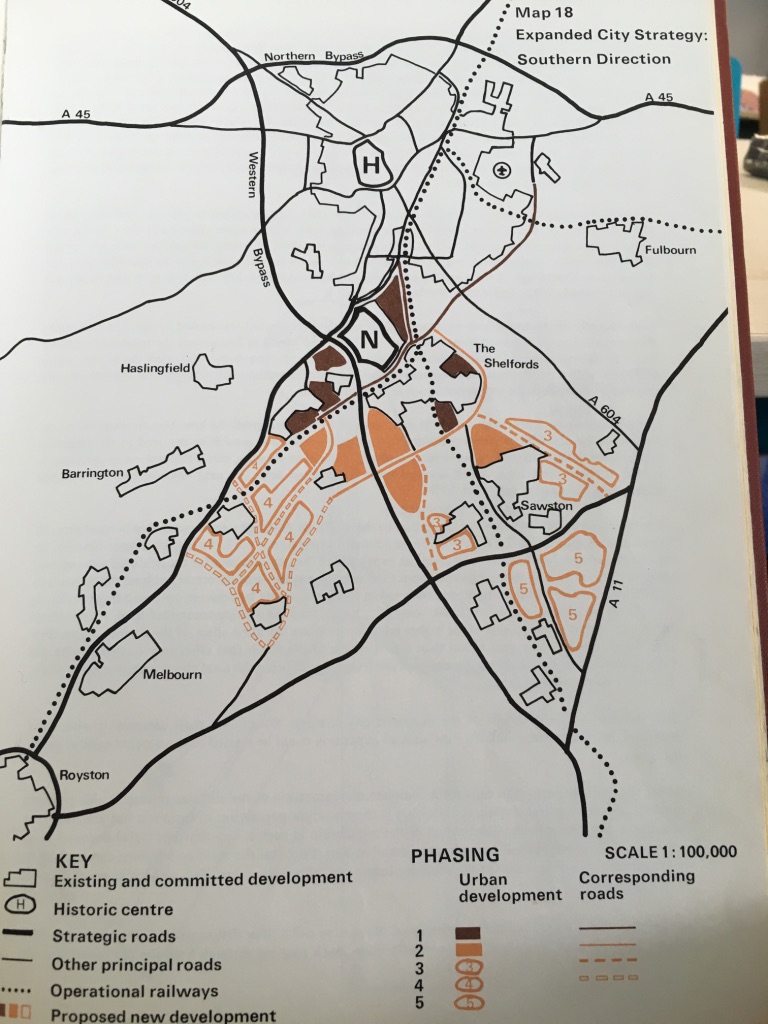

Those who lived through the 1960s and 1970s in Cambridge may be familiar with the trials and tribulations of a changing and growing city – and in particular the controversial proposals from Professor John Parry Lewis.

Above – options from Prof John Parry Lewis in 1973 which proposed expanding Cambridge to 200,000 people by the year 2000. Supported by Labour Councillors, these were thrown out by Conservative councillors on city, county, and the new South Cambridgeshire District councils.

One of the reasons for rejecting the options other than the radical growth proposed by Prof JPL was that he was appointed by a central government-created quango – the East Anglian Economic Planning Council – established by Harold Wilson’s Government and abolished by Margaret Thatcher’s Government. In local government world, if there’s one thing historically that Conservative councillors are instinctively hostile to it is regional government. Especially if it involves bypassing local councils. I found this out early in my civil service days when I worked for the old Government Office for the East of England – established by a certain Michael Heseltine in 1994. (And abolished by Eric Pickles in 2010/11).

One of the things Prof JPL didn’t cover in detail were the governance arrangements. (Or if he did, I missed them in his report – which you can read here). The reason why this matters is that in 1967, Harold Wilson designated Peterborough as a third generation New Town. At the time the populations of both Cambridge and Peterborough were around the same, under 100,000 people. By the late 1990s, Peterborough was heading towards 200,000 while Cambridge was approaching 110,000. Hence in the late 1990s, a boundary commission review shaved Peterborough off of Cambridgeshire County Council and turned it into a unitary council. I’m on public record calling for a unitary council for Cambridge (one now turned into a campaign by the cross-party-and-none Cambridgeshire Unitaries Campaign, calling for (in principle) two unitary councils based around the two larger cities respectively. (Ely being the small city)).

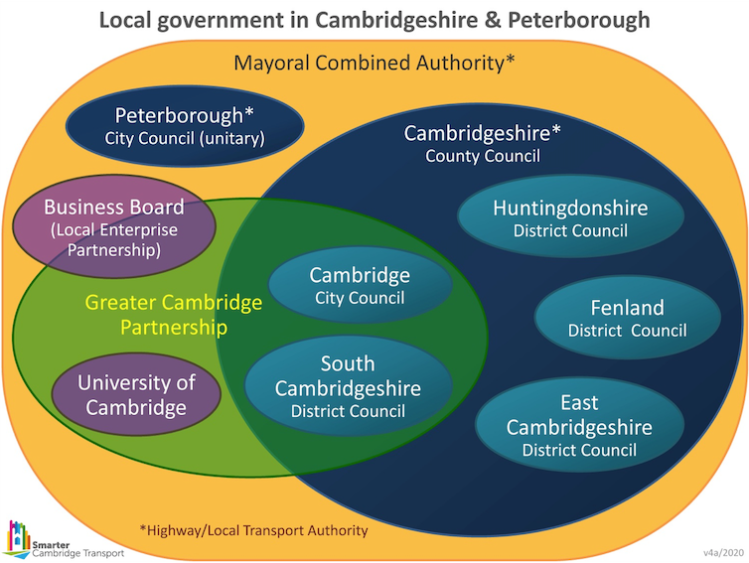

Broken governance

Regular readers of this blog will be familiar with this diagram from the now retired Smarter Cambridge Transport.

I’m generally of the view that I’m not interested in anyone’s case for the growth of Cambridge *unless* they are prepared to discuss:

- The overhauling of the governance structures of Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, and the Cambridge economic sub-region – including boundaries, structures, systems, processes, institutions, and most importantly, legal and financial powers that give any new local council the powers to tax the wealth being generated by the local economy to pay for the much needed infrastructure (housing, transport, cultural, sporting, social, environmental, healthcare, education, the lot).

- The limits to growth – mindful of the Fenland to the north, the high grade agricultural land, and the need to set aside significant areas of that current undeveloped land for restored wetlands, open parklands, reforested lands, and playing fields.

- Inequalities – a robust and radical response to the title of most unequal city in the country, and also a recognition that there are those who do not want Cambridge to become an inclusive city in part because they make money from the ‘exclusive’ brand that the University of Cambridge has.

In my view, none of these can be done without Central Government support. Furthermore, The House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Select Committee reported just over a year ago (31 Oct 2022) that the System of Government in England needed a serious overhaul, and recommended a commission for that purpose. My view is that such a commission should be a full-on Royal Commission Redcliffe-Maud style with powers to commission research projects to bring forward new evidence bases.

“Allowing Cambridge to grow will help to spread prosperity around the country. The most immediate beneficiaries of this will be the towns and villages surrounding the city. This is because cities have spillover effects…However, these benefits will spread far across Cambridgeshire and the neighbouring counties.”

Ramanauskas in Bennett Inst. Nov 2023

Again, I challenge the assumption that this will just ‘happen’.

Former Cambridge City Council Chief Planner Peter Studdert told former city councillors Lewis Herbert and Sam Davies on Cambridge 105 radio that the abolition of the entire tier of regional planning by Eric Pickles was a big mistake. (See my blogpost here). It made the carefully-co-ordinated cross-county-boundary agreements impossible to proceed with. I had a look back at that regional plan (The East of England Plan) in this blogpost arguing that:

- Not everything needed to be in Cambridge, and that a national and regional industrial strategy could ‘spin out’ successful firms/industries to neighbouring county towns such as Bedford – and link them by new fast rail

- That at a county/sub-regional level, new suburban or light rail loops – an extension of the Cambridge Connect Light Rail concept should be built to connect market towns to Cambridge and to each other – stopping off at villages en route, and having active travelways (footpaths, bridalways, cycleways etc) build alongside, as explained in this blogpost.

- New sporting and leisure facilities could be built in the existing and new towns to create economic activity that would benefit from residents of Cambridge and surrounding towns using them. As I mentioned here, a gym and a few yoga classes offered by the science park developers is not nearly enough.

“The planning system needs to be liberalised so restrictive rules about building ‘what’ and ‘where’ can be relaxed. For example, building height restrictions should be lifted so that taller structures can be built.”

That was proposed in 1960 – the less said of those monsters the better.

Above – from RIBAPix here, the abandoned monsters of the Denys Lasdun proposals for science laboratories at the New Museums site, 1960.

Above – me with ugly stuff by one of Cambridge’s most controversial developers, Brookgate near the railway station, and Jones and Hall’s catalogue of carbuncles in their 2013 bestseller Hideous Cambridge.

So much ugly stuff has been built since then that there are calls (from me at least!) for a second edition!

It’s all very well saying ‘Get Building’ but the construction industry collectively has demonstrated time and again that it does not have the competence or capacity to build the homes to the basic standards required by law

I refer in particular to:

- Daniel Zeichner MP (Labour – Cambridge) and his speech in February 2021 to Parliament tearing into the poor new build standards in Cambridge.

- Barratt Homes having to demolish over 80 new homes on Darwin Green at various stages of construction because they and their sub-contractors did such a poor job first time around

- Evidence heard at the Grenfell Inquiry (I wrote about the importance of livestream at such inquiries here) where we heard about an entirely broken system. (Read Richard Millett KC’s quoted remarks here)

In conclusion?

The public policy process to enable Cambridge to grow while minimising the negative impacts and internalising the negative externalities so that the polluter and the financial beneficiaries pay the costs is something that will be very, very complex.

Given that both Conservatives and Labour have indicated they want to see Cambridge grow, whichever of them forms the next government will have to face up to some very difficult challenges. Ones that will involve ministers deciding which interest group they want to p*ss off the least. Because as Cambridge Labour found out the hard way in the late 1990s/early 2000s, if Sir Keir Starmer in government gets it wrong, the local electorate has form in punishing them at the local elections ballot boxes. Just as Cambridge Conservatives found out under Margaret Thatcher & John Major, and Cambridge Liberal Democrats discovered to their cost when Nick Clegg was Deputy Prime Minister – a local political hit they are yet to recover from.

Food for thought?

If you’re interested in the essentials of town & transport planning in relation to Cambridge over the decades, I’ll be covering this in The Great Cambridge Crash Course at Rock Road Library on 25 Nov 2023 from 12:15pm. (Free / donations). See here for details and to sign up.

If you are interested in the longer term future of Cambridge, and on what happens at the local democracy meetings where decisions are made, feel free to:

- Follow me on Twitter

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge.