…subject to a series of conditions attached to that planning permission – you can read the news report in the Cambridge Independent here. You can also browse the website of the developer and new owners here.

Again, this blogpost comes with a cautionary note for you, the reader, to make sure you are aware of what The Law as enacted by Parliament, and Government Policy as decided by ministers, and a Local Development Plan – whilst created by councils have to be scrutinised by planning inspectors, hammered by lobbyists, and ultimately approved by ministers (again).

“That’s impossible – we’d all have to take university courses in town planning!”

Therein lies a major fault line in our democracy: decisions on what happens in people’s neighbourhoods, towns, and cities can be very heavily influenced by people who do not have to live with the day-to-day consequences. Something to put to the candidates standing for political parties with a chance of forming the next government?

What’s happening in Cambridge is but one example of the symptoms associated with broken systems of civic and political governance. Have a browse through the comment pieces from the Institute for Government to get a feel of how deep and wide-ranging the problems are.

The fate of the Grafton Centre reflects a series of governance failures. Big ones.

A failure of localism

A few months after I left the civil service, ministers trumpeted their much-publicised Localism Act 2011 which included a plain English guide that you can read here. It was supposed to mean local areas would have much more power to take decisions for themselves rather than having Whitehall imposing things on them.

The problem with the rhetoric is that it didn’t, and does not match the economics of Thatcher and Reagan – the likes of which we’ve had various forms of as long as I have been alive. This is not to pretend everything was splendid in the decades before – they weren’t. The key theme from 1979 onwards was the scaling back of the state as an institution to solve collective problems. The model of local public services moved away from your local council being the provider of services to the commissioner of services provided by someone else. Most prominently, refuse and recycling collections, social housing provided by housing associations, and the provision of bus services are the most prominent.

In the case of the old residents of The Kite before the Grafton Centre was built, local residents came up with their own proposals in 1976 for renovating their part of town that had been allowed to develop as a slum – mainly by its main landlord, Jesus College Cambridge. That alone speaks volumes and is worthy of greater study. A coalition of big landlords including the college, Grosvenor, the Cambridge and District Co-operative Society (long since vanquished), and Cambridge City Council (in the late 1970s controlled by the once-mighty Cambridge Conservatives) decided to go ahead with comprehensively redeveloping the area and creating a second retail centre for the city – building on proposals signed off by central government in the 1960s.

Was The Grafton popular?

Of course it was – a multi-storey car park was ideal for people in rural areas becoming frustrated at austerity-hit bus services that would later be privatised. That’s not to say all shops did a booming trade. Some were more successful than others, while the fortunes of big name brands meant that prominent names from the 1980s such as C&A were no longer there by the mid-1990s. There were also the fortunes of the national economy and of local firms and employers that inevitably had an impact on people’s disposable incomes. You can browse through those 20th Century stories in the British Newspaper Archive here if you’ve got a subscription, or for free in your nearest public library.

Above – over 15,000 hits for the term “Grafton Centre” in the Cambridge Evening News during the 1980s-1990s – should any teenager want to do an extended research project for college.

“Why is it that so many people have been concerned about the centre being converted into a sci-tech centre?”

The rhetoric from the big science sectors amplified by politicians, lobbyists and academia has come at a cost. A social cost. One that has given the impression to some of our lifelong residents that Cambridge is ‘not for them’ because they are not highly qualified scientists. Combine that with impossibly high earnings to housing costs ratios and you can understand the distress of people finding themselves priced out of the city they grew up in. Don’t pretend that there is not a social – and ultimately a financial cost to this form of gentrification.

“Data shows more than 34,000 households placed out of area last year, with some moved more than 200 miles away”

Matthew Weaver in The Guardian, 28 Aug 2023

“Three-fold increase in council tenants moved out of their local area in last 10 years, figures show”

ITV News 30 Sept 2021

These are just some of the items that compound a housing crisis of families living in slum accommodation, over-stretched and under-resourced council housing teams, charities crushed by demand for their services in the face of declining donations, and successive governments that churns through housing ministers at a rate of one a year meaning there is no policy continuity because ****housing policy is complex**** and it takes about a year to familiarise yourself with the basics. As I found out the hard way during my year in housing policy in Whitehall.

But homes are property, and shops are property, And property is a financial asset that can be traded on international financial markets. And assets can be stripped of their value. In the mid-1970s there was the option of regenerating The Kite. The Conservative-led council turned it down in the teeth of opposition from a number of prominent councillors including the late Colin Rosenstiel of the Liberals, later the Liberal Democrats.

“In 1976, as much due to divisions within the Labour and Liberal parties as for any other reason, the Tories gained control of the Council and decided to proceed with the redevelopment of the Kite.”

Cllr Colin Rosenstiel in 2001

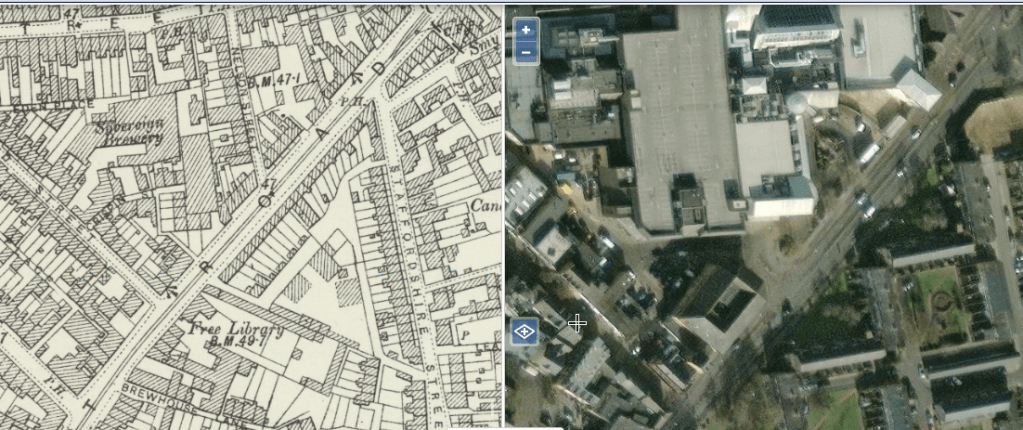

The money and the political culture within the Conservatives was clearly in favour of comprehensively redeveloping the area to create a new sort of ‘retail experience’ similar to that of the Lion Yard – an enclosed space full of shops that people could drive into and out of with ease. Hence the road widening programme of East Road that saw the southern side of properties flattened as part of the comprehensive redevelopment. If you browse the ‘side-by-side’ map of East Road via the National Library of Scotland here, you can see how the redevelopment of the St Matthew’s Estate to the bottom-right, alongside the road-widening of East Road involved levelling an entire row of houses.

Above – East Road (with tramlines) circa 1900 with a more recent aerial/satellite photo, National Library of Scotland here.

Above – The old Kite in the 1940s from Britain From Above.

You can just about make out East Road at the top-right. the familiar arches of the old Eden Baptist Chapel (presently the Fitzroy Street entrance to the Grafton), and the white 1930s building of the old Co-op, demolished alongside its older sister building (built in 1895) in the 2000s to make way for John Lewis, then Primark. To the top-right of that is the distinctive maltings-shaped roof of the old Sovereign Brewery.

I’m not going to ‘romanticise’ about the poverty that the community faced.

The more important issue for me was that they came up with their own solution to improve their area, and were turned down – ironically by a Conservative Party that 30 years later would be championing ‘localism’ of this very sought. On paper at least.

One of the criticisms levelled at Labour in Tony Blair’s and Gordon Brown’s years was that they did not rein in the worst excesses of the corporate retail sectors – enabling some of the worst cases of asset stripping that cost thousands of jobs across towns and cities.

I wonder what the politicians of the era think now about whether they could and should have done far more to prepare for the impact of online shopping on the high street. Not least because one of the comments I see quite often on local social media pages is that shopping is not only a function in and of itself, but it is part of a wider set of activities that involve socialising and meeting people out and about. Not in the ‘Well I can fit you in for an 11am brunch before I go for my…’ stereotypical life-by-diary-manager, but the sort of lives that people not in full time employment for whatever reason might live – one where passing familiar faces on a daily basis is part of living. It’s something I recognise in many of the many grandparents that live in my part of Cambridge who are the parents of people I went to school with back in the 1980s & 1990s – and who stayed around. Many of their offspring don’t live locally either because of the housing crisis or because in their career paths Cambridge simply does not offer the sorts of jobs they do – in part because in our over-centralised country it involves living/close to and working in London.

The loss of anchor shops and institutions

The Grafton used to have Mothercare, BHS, Debenhams – three shops whose parent companies imploded in the face of various financial problems including taking on too much debt. Throughout the 2000s we saw the decline of music record shops (Virgin, Our Price) and photo processors due to technological change. Part of the former was that the record companies were making fortunes in the 1990s to such an extent that amongst other things it created a huge financial incentive in the computing sector to come up with something that would a huge share of that music market by making existing listening systems obsolete. What was meant to be an anchor bookshop (Heffers) decided to close its Grafton Centre shop.

Finally there was the removal of the direct bus services from South Cambridge which took away the potential custom from half of the city. A decision by a couple of people at Stagecoach. This despite the fact the 1995 revamp created a bus stop located just outside the brand new multiplex cinema built there. And it was ideal for so many people to use public transport because a short walk to a neighbourhood bus stop would drop you literally outside the entrance of the cinema. We don’t have that anymore.

Faced with the decline in retail and in the context of a global marketplace, quite understandably the former owners decided to cash in after a failed revamp in the late 2000s/early 2010s. With the huge sci-tech bubble and international firms looking for every possible site going in Cambridge to turn into something science-related, the firm was sold to an international firm having been marketed as an ideal place for laboratories and things – something I took issue with back in summer 2021.

History repeating itself?

Just as the families of The Kite were moved out to edge of town council estates in the 1970s and 1980s having little say or influence on the future of their neighbourhood, so the working class shoppers of The Grafton Centre have had little influence on what happened to the shopping centre that they were familiar with. They had little influence on the change of the bus services – ministers having moved to a catastrophic privatised model in the 1980s, one not reversed by Labour when it had the chance.

“Why didn’t the owners simply reduce their rents like basic market theory says should happen? Supply and demand and all that?”

In principle that is what the basic model says. But then models are, by definition simplified versions of real life to enable analysts to identify what might happen if certain conditions or variables – or ‘stuff’ is changed. Cut business rates and firms face lower costs, so more might want to expand or more new businesses may want to set up shop. But this assumes something about the costs faced by the land owner and shopping centre owner. How much does the maintenance cost?

And if the shopping centre is bought out by another company, then chances are that company will be looking for a return on that investment – whether to pay shareholders, pay lenders that stumped up the cash for the stakeholders, or to provide an income for institutions such as pension funds and insurance companies that often invest in such things. Therefore there’s only so far a shopping centre owner is willing to reduce rents by. If it is lower than the repayments it has to make, it won’t rent out the properties – more likely they will try other things, including finding alternative uses. And that is what happened here. Retail wasn’t providing big enough returns, while the projected sci-tech bubble very much is. For now. With ‘Cambridge’ being a global brand (despite the place being treated like a market town/play thing by ministers and Cambridge University bosses) and high projected returns, old office blocks, shopping centres – even former municipal tips are being converted for sci-tech purposes.

- Grafton Centre = shopping centre

- Landfill site off Coldham’s Lane near Cherry Hinton

- Westbrook – old office block/complex off Milton Road

- Beehive Centre retail park

Above – image from the planning portal ref 23/02685/FUL

“What’s left for the people who make up the city of Cambridge?”

Former Vice Chancellor Sir Ivor Jennings QC stated the following to an audience in Cambridge on 31 May 1962:

“Cambridge is more than a University, it is a City in its own right, and its significance as a regional centre has grown and will continue to grow.”

Sir Ivor Jennings QC, 31 May 1962 quoted in the CDN 01 June 1962

Is Cambridge a city in name only? Because the municipal council – Cambridge City Council – is so enfeebled as an institution that it can no longer afford to have The Guildhall as a functioning venue to deal with public enquiries.

As one fellow resident who moved to the city many years ago from continental Europe asked me: “Where is the civic pride?”

Exactly.

“Are there any solutions out there?”

One think tank is working on it:

“At the heart of [our work] is the belief in community power – the idea that people should have more say over the places they live and the services they use. We believe a paradigm shift is needed to create sustainable public services, better places to live – and enhanced wellbeing for all.”

New Local – a public policy institution

(You can see their governance and funding links here). For those of you who are members of the Labour Party, Co-operative Party, or a TUC-affiliated Trade Union, the policy document written by a group of Labour councillors on a vision for community power set within their party’s values, is here. I’d be interested to read similar proposals from other political parties on revamping how our towns and cities are governed in the face of multiple, massive complex challenges.

Food for thought?

If you are interested in the longer term future of Cambridge, and on what happens at the local democracy meetings where decisions are made, feel free to:

- Follow me on Twitter

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge.

Below – Cambridge Matters magazine – produced by the city council. You can read online copies here