The report from the Institute for Government might have been missed by most people, but as Harriet Harman said earlier, this is *really important*

Image – How to be a Minister, by former minister John Hutton with Leigh Lewis

You can watch the summary video below:

The summary proposals are:

- The government should agree Priorities for Government at the start of a parliament and announce them as part of a modernised King’s Speech.

- The prime minister should appoint an Executive Cabinet Committee made up of a few key ministers [similar to ‘The Quad’ in the Coalition].

- The prime minister should appoint a new, senior first secretary of state with responsibility for delivering the government’s priorities and ministerial responsibility for the civil service.

- The Cabinet Office and No.10 should be restructured into a Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet and a separate Department for the Civil Service.

- There should be a new statute for the civil service and the Civil Service Board to hold its leadership accountable for reform priorities.

- The roles of cabinet secretary and head of the civil service should be filled by separate individuals.

- The Priorities for Government should be fully reflected in a new shared strategy, budget and performance management process owned collectively at the centre.

You can read the full report here (click on the pink download icon)

I’m not going to try and interpret the details because the report already does that. Instead, my first thoughts are on the other parts of the state that need a similar root-and-branch review. Without this, the recommendations of the IfG will collapse under the weight of the multiple demands on senior ministers.

Separate the UK Parliament from the UK Government

The job of being a Minister of the Crown, and of being Member of Parliament should be two separate full time jobs – and are full time jobs if the office holders are doing the job properly. Those MPs that spend extended periods of time on well-remunerated consultancies or plush directorships is time not spent in their constituencies or receiving briefings from experts on a range of problems and issues that their constituents face.

Having seen close up the work that ministers and MPs do, I’m astonished that anyone can manage such long hours at such an intensity. Inevitably the machine – and some of the people within it, break down.

Far better to have a system where the leader of a registered political party whose candidates form the majority of MPs in the House of Commons following a general election, becomes Prime Minister, and that Prime Minister then nominates individuals for high ministerial office subject to Parliamentary Approval – similar to the USA. The system we have requires political parties looking to form a government to undertake all sorts of underhand actions to get a critical mass of candidates *of ministerial calibre* into ‘safe’ seats. Mr Crick is keeping a watch on the candidate selection processes of the main parties. The point being that a constituency might get a useless local MP in a safe seat who is a crackingly good minister – but that means those who might be in the greatest need end up losing out because said minister inevitably neglects constituency work for ministerial work.

There should be a minimum set of standards that constituents should be able to expect from their MP

Not only does this manage the expectations of the general public, but it also protects MPs from vexatious or party-political complaints. Part of the root cause of the problem here is the lack of civics and citizenship education both in schools and in society – not just adult education colleges.

The old ‘gentleman’s conventions’ of old no longer hold sway – the one where it’s left to individual MPs to start from scratch and work things out for themselves, leaving it to the electorate to decide 5 years afterwards if their MP has been ‘any good’. How is a society that is not educated on the basics of democracy, government, and civics supposed to know what the difference between an excellent MP and a weak MP is if they’ve only ever experienced the latter?

“If I hadn’t seen such riches, I could live with being poor”

Some of you may get the musical reference too.

The centre of government is trying to do too much from the centre – involving itself in things that it should not be concerning itself with. But the lines of financial accountability in our political system, along with party political games make this all too easy to get caught up in

The financial line of accountability with central government is this:

Taxpayer -> Parliament -> Ministers -> Civil Servants -> Public Services

The public/taxpayer receives public services, and when things go wrong and have exhausted local complaints processes, they are able to go to their MP. If their MP cannot resolve the issue locally, the MP contacts the Minister (either in writing or in Parliament through an oral question). The minister then finds out from civil servants and the public services concerned what the problem is, and responds back to the MP, who then informs their constituent of the outcome. When I wanted to find out about dealing with the lack of an community adult education college in Cambridge, I emailed my MP and asked him to contact the minister responsible to find out what the process was for establishing one. The minister with policy responsibility for adult education at the Department for Education responded – and I was surprised to find that unlike the olden days, anyone wanting to set up a new lifelong learning college that receives state funding must get permission from ministers. (S16 & S17 Further & Higher Education Funding Act 1992).

“Why do ministers need to approve local lifelong learning colleges?”

That’s what I don’t get. In the olden days we didn’t need ministerial approval. Dorothy Enright when transforming the Cambridge School of Arts, Craft, & Technology (later CCAT & then incorporated into Anglia Ruskin University) didn’t wait for ministerial approval when she spent part of the 1920s surveying the major employers in Cambridge to ask them what their skills and training needs were – the result being the transformation of the courses on offer, and an increase in the number of workers being sent by their firms on training courses there.

“Ministers will point to combined authorities”

Structures that, with the exception of the London Assembly, have ***really weak*** oversight and governance structures given the lack of an effective directly-elected assembly and independent revenue-raising powers to accompany them. The malfunctioning of the CPCA has hardly been an advert for the model.

Empowering local government so that it does not have to go cap-in-hand to Whitehall all the time

That also should include increasing the pay (let’s get rid of the over-complicated system of expenses) of local councillors so that more people from diverse background face fewer barriers, and enable them to take on some of the functions that were needlessly centralised. Like education and schools. Rather than dealing with the problem of struggling local councils and struggling schools, ministers chose to go with the academies system that broke the line of local democratic accountability on how taxpayers’ monies are spent. Furthermore, the creation of new charities for academy chains inevitably created more work for the Charity Commission – the sector’s regulator.

Municipal/local government inevitably struggles in a world of fragmented, privatised, and outsourced public services

I ran a workshop for some urban planning students from Japan earlier today – they were visiting Cambridge as part of a two week crash course to learn the essentials about how our system functions and malfunctions.

As an icebreaker, I asked them to tell me their name, and *one* thing they would like to see improved or dealt with in Cambridge given what they have experienced.

At the end of the session, the two observations I came away with given their range of questions, were:

- They were surprised at how over-centralised the UK system of government is – in particular how much power that ministers have

- They were surprised at how poorly-performing private companies were allowed to get away with continued long term poor service delivery – especially when, as in the case for buses, they charge so much.

On the second point, this is where I said to them that the UK needs to learn from Japan – especially with the rail sector and the quality of its transport systems.

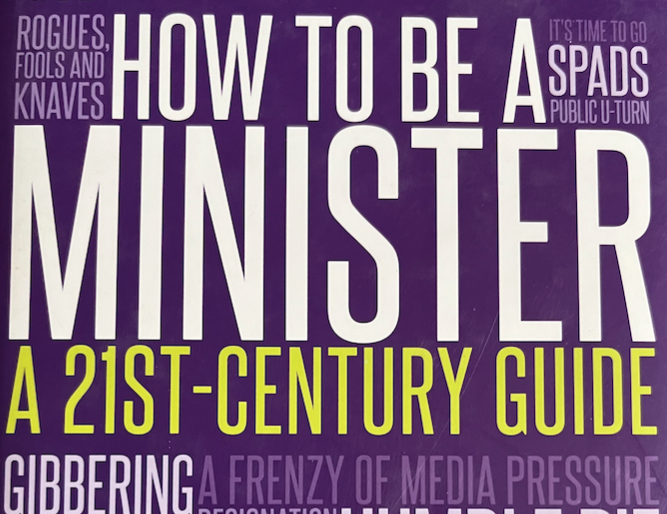

The UK hasn’t always been so fragmented – as Leicester City Council demonstrated in their civic guide from 1939

Above – from the old Corporation of Leicester/LCC (1939)

At an earlier workshop for the Cambridge University Climate Society, I invited students to look at the diagram above-left, and list which functions had been centralised, outsourced, or privatised. In that sense, the Conservatives under both Thatcher and Major achieved their goal of the destruction of what was once called ‘Municipal Socialism’.

Yet for all of its drawbacks, I’m not entirely sure that what their party replaced it with has turned out to be much better – especially if we compare the differences in service charges. How much money for example is being extracted from local economies by private landlords that now rent out former council houses at higher rents? How much extra are passengers paying for rail fares as private companies are bought and sold on international markets? How much of the ticket fare goes on servicing debt from asset-stripping owners past and present, rather than into productive investment (eg new more efficient machinery)? The same goes for utility bills.

It’s not just the UK that has these problems. Australia has similar issues.

Warning: Not Safe For Work!

And if you want to see their spoof take on UK politics…Again, not safe for work!

Above – part of me feels like I need to wash my ears out after all that swearing!

The Power with Purpose report needs to sit alongside significant improvements to a host of other institutions, and the bringing in of new policies that will strengthen, not weaken our democracy.

I remain to be convinced that senior politicians and their policy advisers appreciate that point. If the Power with Purpose report stays as a standalone document, its impact will inevitably be limited. If it’s part of a wider overhaul that helps us face the huge shared challenges such as those the former prime ministers Gordon Brown and John Major outlined at the report’s launch, then the positive impact of the reforms could be far greater.

Food for thought?

If you are interested in the longer term future of Cambridge, and on what happens at the local democracy meetings where decisions are made, feel free to:

- Follow me on Twitter

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge.

Below: You and The State – from 1949. Civics education matters.