The winner of the Wolfson Prize 2014 highlights issues that the people of Cambridge need to be aware of when scrutinising and challenging decisions made about our city’s future.

You can read the documents here

As the firm stated:

“Uxcester Garden City: Our essay describes a plan to create a garden city of almost 400,000 people by doubling the size of an existing city. This is based on a real city, if not one that we identify. We have called it Uxcester and created it from an amalgam of at least six other cities, all places with populations nearing 200,000, with long histories, established institutions and settled communities.”

http://urbed.coop/wolfson-economic-prize

“Why didn’t they call it…I don’t know… Camford? Or Oxbridge?“

Too obvious.

“How does it compare with Gove’s Case for Cambridge?”

Neither has a set of firm geographical geographical boundaries for a start. And Gove’s fantasy involves more than quadrupling the size of Cambridge by 2050.

“Uxcester is a lovely place, with two millennia of history, a complex local government structure and an engaged and articulate local community. There are at least a score of places like Uxcester in the UK”

There’s complex and complicated. Complex is inherent in its nature, while complicated is something that has been made to be so – whether by design, accident, political/financial gain, or sheer incompetence.

“What’s the opposite of Uxcester and how did such places emerge?”

Good question. Let’s try this:

“Blandsville is a boring place that was recently built by an oligarchy of mass builders as a profit-making value-extraction exercise, has no history, has no governance structure beyond a parish-level council because all of the decisions are taken elsewhere, has few amenities or public services of its own – most of those that exist are privatised or outsourced, is cut off from the place where decisions are taken, has a population suffering from the consequences of multiple deprivation, and a very high turnover of population meaning there are very few people and institutions willing to fight for people and place – those that stay behind are often those moved by the state from more affluent parts of the region where ministers refuse to allow council housing to be built – most of the existing stock having been sold.”

Knowing what outcomes/results to avoid (and how to avoid them) is just as important as politicians knowing what they want and knowing how to get it.

“The Case for Cambridge – a Reverse Thinking Exercise”

This is something I learnt in my civil service days on scoping a brand new policy. In order to carry out a policy risk assessment, you need to work out all of the possible ways your policy could go wrong – and achieve the very opposite of what you want. And we have two local case studies to look at: Cambourne and Northstowe. The problem with Gove’s plan for Cambridge is he’s left himself no time to look back at the historical record because he made his announcement with less than 18 months before a general election. The closer we get to a general election, the less important his opinions become, and the more important the views of his opponents in the Labour Party shadow posts become. Because if, as looks likely, Labour form the next government, then they will have to decide how to proceed – and they could simply scrap everything Gove has commissioned and say instead that they will proceed with the existing emerging Greater Cambridge Local Plan 2031-40.

In the case of reverse-thinking, imagine you are a major financier based on some obscure tax haven and want to make a fortune on this – knowing that it involves building the mega-slums of the 21st century. So, how do you go about doing this?

Things could include:

- Donate large amounts of money to the political party in power – not all at once and not all to central office, but via splendid chaps, associates, and people who live in the constituencies of influential MPs/Ministers.

- Have your lobbyists establish themselves on government task forces, independent advisory panels, expert forums to influence policies that might be bad for your businesses.

- Put some money behind public policy institutions/think tanks who can argue the case for you but for which there is no paper-trail leading back to you.

- Get your paid up people to network, network, network – and make friends with junior staff in media organisations so that if there is a last minute seat that needs filling on a late night paper review or a ‘contrarian take’ needed in the interests of balance, they have got your people on speed-dial.

- Put some money behind favourable media outlets to make some noise to drown out anything that could be put out by your opponents.

- Put funds behind ‘prestigious prizes’ that support the sort of designs that will make you a lot of money

…and you are halfway there to getting your way

Which is also one of the reasons why more than a few people in the Labour Party have concerns about the levels of funding that are now coming from the corporate sector. The concern being ‘cash for policies’. The problem is the incentive that the existing model of party funding creates. i.e. a strong financial incentive to create policies that will attract a small number of very large donations rather than the effort needed to get a very large number of small donations from grass roots members.

Because of the fortunes that stand to be made from brand Cambridge, there’s a huge public interest in ensuring the benefits are not captured by the powerful for the few: privatising the profits, and socialising the losses

The Uxcester case study looks at several options on how to manage the risks

“We suggest a ‘Social Contract’ that would address the concerns of this community. Rather than a future spent fighting years of ill-planned development, the Garden City would offer the prospect of a clear 40 year vision that accommodates development while minimising its impact.“

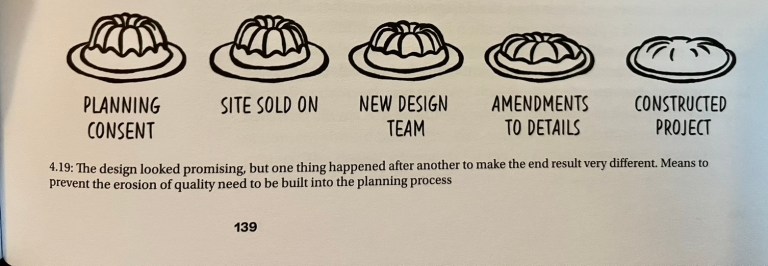

Yet as Cambridge found out with the railway station…exactly

“Visitors arriving by train are now greeted with a generic clone-town scene more like a suburban retail park than an illustrious seat of learning. Reconstituted stone fins line the front of a broad, bland office building, presenting a beige frontage of Pret, Costa and Wasabi outlets to the new station square. The insipid facade of a squat Ibis hotel frames its other side, looking on to a public space seemingly designed more with cars than people in mind.”

Olly Wainwright, The Guardian 13 June 2017

Of course since then, more works have been completed and more improvements have been made. But recall the original vision…

“…the promised bounty of a “proper transport interchange”, affordable housing, healthcare facilities and a new heritage centre, which was planned to be housed in a majestic old grain silo next to the station.

Wainwright (2017)

How is a social contract going to close the loophole of a firm going into administration, being bought out of it with an ‘off the shelf’ package (completely legally) by some of the previous firm’s directors, and then reneging on the previously-agreed amenities? Because Uxcester’s plan states:

“We are suggesting a ‘Social Contract’ with the good people of Uxcester to ensure that the benefits of the Garden City are spread across the whole population. For every acre of land developed for housing they would get back an acre of publicly accessible green space; the new development would fund a new tram system as well as the upgrade and expansion of existing services and facilities.”

Uxcester (2014) p10

In the present system, a developer who can commission an ‘independent’ consultant to say that providing for such things in ‘viability assessments’ makes developments unviable/unprofitable means either the nice things have to go or the development does not get built. What power should the state have to say to developers and land owners: “Use it or lose it”?

This is why governance is ever so important – and the state needs to have both a much more active role *and* a financial stake in the success or otherwise of any proposals

Yet as we know, the withered state of local government means it is not fit for purpose to take on that active role. Furthermore, I remain to be convinced that the system of combined authorities that lack directly-elected assemblies is the right one to hold combined authority mayors to account. Especially ones that had so little public involvement in their creation – such as in Cambridge.

The challenge then is to create a system and structure of governance that deals with the things the Uxcester proposals list on p25/28

“We need to replicate the conditions to create diversity and adaptability in the new development. In doing this we need to learn from the past:

- We need to create a land ownership structure with a long term interest in the quality of the place.

- We need to put in place strong masterplans that give shape and coherence to the development but…

- We need to allow development to proceed plot by plot in an incremental fashion.

- We need to put in place a clear set of development rules that give certainty without being overbearing or petty.

- We need to create incentives to invest in the quality of what is built and instil a sense of pride and ownership.

- We need to allow plots to evolve both during and after construction, encouraging extensions, live work units etc…

- We need to create long-term secure income to ensure the upkeep and management of the neighbourhood.”

Learning from the past – Elizabeth Halton’s crash course in housing policy 1939

You can read her pamphlet here – which for a Conservative councillor on the old London County Council is a radical pamphlet when compared with her party’s successors today. I really like the way she peppers the pamphlet with a series of open questions to the reader.

Mindful she was writing the below in 1939, note what she says about planned towns.

Above – Halton (1939) p29

It’s easy to criticise previous generations for building such low-density housing with large gardens, but back then the impact of the U-Boats combined with the very low productivity of UK agriculture during the First World War created a national security crisis. Hence having back gardens with allotments made sense – as Britain found out the hard way again. (It was that food crisis that also resulted in more of The Fens north of Cambridge being brought under the plough – hence why tree cover there is so low.)

Getting the size right

Elizabeth Halton (later Lady Pepler) returned to this issue in 1945 in a book for the Association for Education in Citizenship in a book called Our Towns

Above – Elizabeth Halton (1945) Our Towns p6

Note the road accidents and the the traffic jams mentioned. And the balance of getting a town large enough to sustain a decent variety of public services and amenities, but not too big so as to be out-of-control. This is where Rob Cowan’s excellent book on Essential Urban Design (that I wrote about here) comes in.

Cambridge Station anyone? From Cowan (2021) Essential Urban Design p139

If anyone wants a copy of the book, the cheapest version is available direct from the publishers.

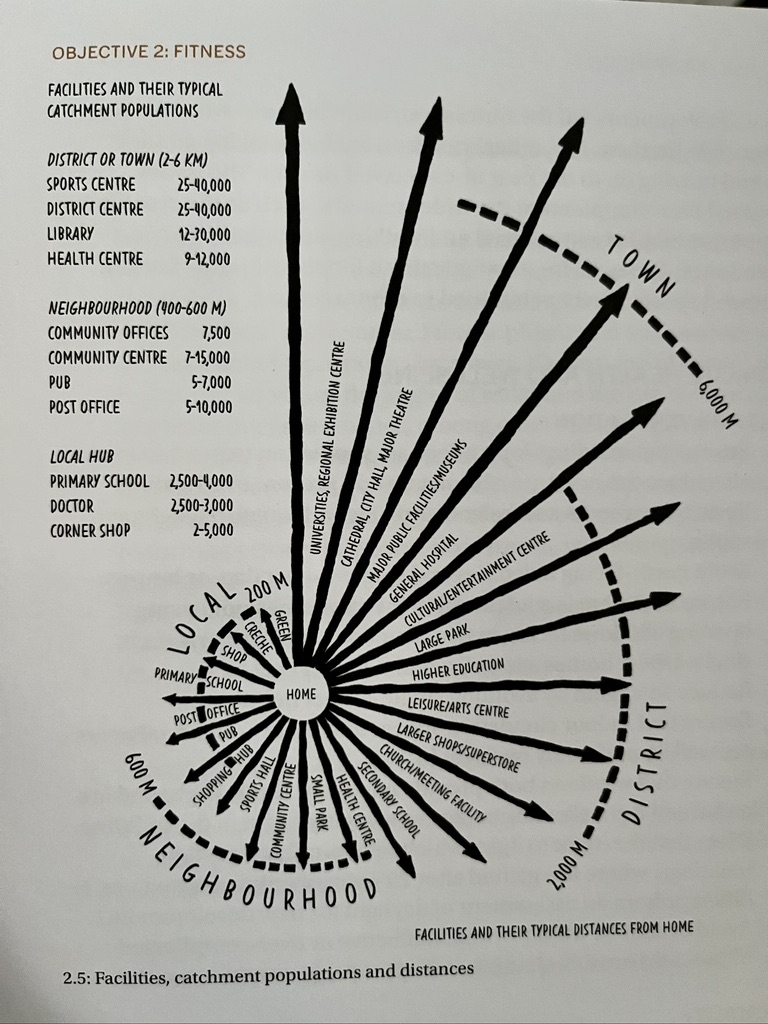

Below – the different facilities and the populations needed to sustain them.

Above – at the most local of levels there should be the equivalent of a village green or small park within 200 metres of every house/home/flat/dwelling.

In the case of Cambridge, we could run a fairly quick audit of a selection of amenities to compare the ideal catchment’s Mr Cowan cites, vs the reality – at which point we would find out very quickly that Cambridge is already chronically under-provided for. The Cambridge Corn Exchange, The Junction, and Parkside Swimming Pool tell us that. Please do not equate that as making a profit/surplus. It’s easy to remember the price of everything and the value of nothing when it comes to what cities need to be more than just liveable.

In terms of what a city should have, again lets look back to Planning – The Architect’s Handbook in 1948 and look at their contents list. What would a refreshed list for the 21st Century look like? Noting that this is building for the mid-late 21st Century rather than the present era or even trying to make up for the decades we’ve just lived through. Something to discuss at a future Together Culture event?

If you are interested in the longer term future of Cambridge, and on what happens at the local democracy meetings where decisions are made, feel free to:

- Follow me on Twitter

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge.

If you want some ideas on how to go about this, pop into Together Culture on Fitzroy Street down the road from The Grafton Centre.