I’ve been buying cheapo old books on buildings and things again…while being house-bound with chronic fatigue and post-exertional malaise. (No, I don’t know why I stayed up until 02.30am to finish this when I started it before midnight!)

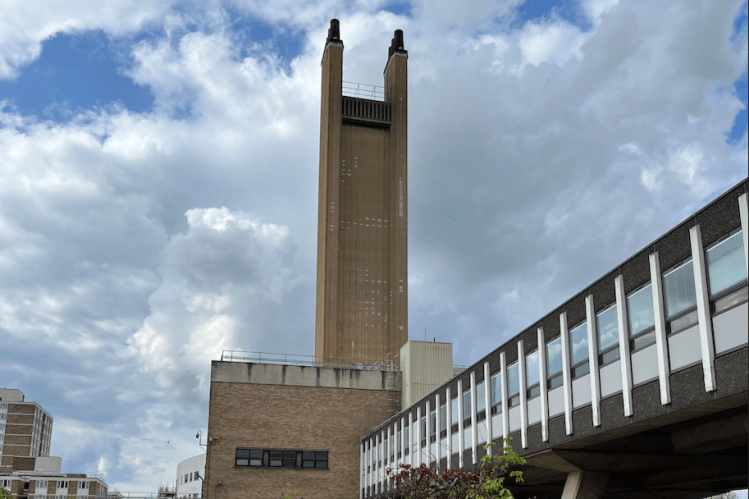

It might seem strange to follow a post that featured one of the most famous brutalist structures in East Anglia with a moan about building design (Addenbrooke’s chimney – it might be a big, brutal, ugly chimney but it’s ***our big, brutal, ugly chimney so leave it alone!!!***)

Above – Addenbrooke’s Chimney – taken by me probably after coming out of a meeting, an out-patients appointment, or A&E (there’s an M&S food hall in the concourse)

This week I learnt architecture has manners – good and bad

Above – Trystan Edwards from 1944 – An essay on the social aspects of civic design

The reason why I picked up on it was because the direction of travel with local government in Cambridge seems to involve the sector and the functions of the councils retreating from the city centre as it continues to decline, combined with the continued expansion of the city. At some stage ministers and senior politicians of all parties will have to grasp that contradiction.

It could have been so different if Labour had won the 1970 General Election

I wrote about this in Lost Cambridge here. Basically because the regional economic planning structures would have corresponded with what Redcliffe-Maud proposed for the overhaul of local government in England, and quite possibly what Prof John Parry Lewis ultimately recommended for Cambridge.

The Manchester Professor worked on an assumed population growth to around 200,000 people by the Millennium – which is what Peterborough broadly achieved when it was designated a third generation Newtown in 1967. What doesn’t seem to have been accounted for in JPL’s map is the increasing housing density that we see in more recent developments in the face of higher land prices combined with lessons learned about needing greater population densities to sustain local services. In the 1970s slum clearances were still in progress even though the problems with architecture, building materials and urban design were materialising. What would his proposals for housing design types have been, or would he have left that to others?

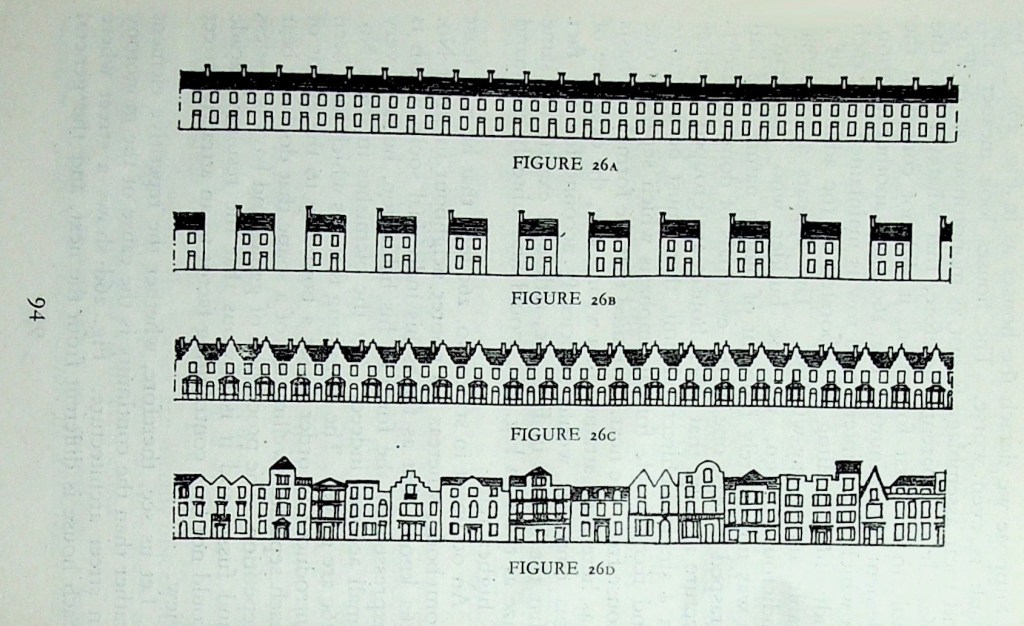

Monotony? ***Down with that sort of thing!!!***

Trystan Edwards first published his book on about the manners of architecture in 1921 – I got hold of the 1944 edition. It’s a cheap-as-chips number (Wartime restrictions – paper was rationed) but there are some things where a picture needs no words!

Above – Trystan Edwards (1944) p94 complaining about ‘the bugbear of monotony’ with housing developments

I can understand why he complained about them – whether working class housing packed together by speculative builders through to the mass-produced ‘units’ built to identical designs that made it easier for the quantity surveyors and the builders to build to the same designs. One of the things former South Cambridgeshire MP Heidi Allen (2015-19) called for was the breaking up of large plots often sold to the volume builders so that small independent firms of builders and architects could break up the monotony of the dull pattern books that too many of the volume builders have.

Architecture and democracy

In Claude Lafayette Bragdon’s book Architecture and Democracy (which I thought was a modern title but turns out it was published in 1918) he mentions the Greek/Irish/American/Japanese writer Patrick Hearn who observed the impression of what American cities of the early 20th Century made to Japanese travellers educated in the late 1800s.

“…the ceaseless roar of traffic drowning voices; by monstrosities of architecture without a soul; by the dynamic display of wealth forcing mind and hand, as mere cheap machinery, to the uttermost limits of the possible.”

Above – Bragdon citing Hearn, 1918 here

As Bragdon’s wiki page states: “In numerous essays and books, Bragdon argued that only an “organic architecture” based on nature could foster a democratic community in an industrial capitalist society.”

I found this take by Bragdon in the paragraphs that followed to be just as striking:

“The buildings are there, open to observation; rooted to the spot, they cannot run away. Like criminals “caught with the goods” they stand, self -convicted, dirty with the soot of a thousand chimneys, heavy with the spoils of vanished civilizations; graft and greed stare at us out of their glazed windows — eyes behind which no soul can be discerned.”

Above – Bragdon (1918) p2 of the main body

Dirty with the stains of a thousand exhausts might be more apt for some of the buildings in Cambridge along main roads that have gone up but have not been maintained well. After all, once the limited company that was created to get the building built has been dissolved and the institutions that financed it have squirrelled away the profit, where does responsibility and liability reside?

Perhaps what’s even more striking are the prophetic words about the separation of the building structures from the building exteriors.

“With the modern tendency toward specialization, the natural outgrowth of necessity, there is no inherent reason why the bones of a building should not be devised by one man and its fleshly clothing by another, so long as they understand one another, and are in ideal agreement, but there is in general all too little understanding, and a confusion of ideas and aims. To the average structural engineer the architectural designer is a mere milliner in stone, informed in those prevailing architectural fashions of which he himself knows little and cares less”

Which reminds me of the Grenfell Tower Inquiry and the cladding scandal (and screwed up business practices) exposed by it.

“Now that “twilight of the world” following the war perhaps will witness an Avatara — the coming of a [supernatural?] World-Teacher who will rebuild on the one broad and ancient foundation that temple of Truth which the folly and ignorance of man is ever tearing down. A material counterpart of that temple will in that case afterward arise.”

We’re still tearing it down! He concluded:

“Following the war the nation will be for a time depleted of man-power, burdened with debt, prostrate, exhausted. But in that time of reckoning will come reflection, penitence.

“And I’ll be wise hereafter,

And seek for grace. What a thrice-double ass –

Was I, to take this drunkard for a god,

And worship this dull fool.”

“With some such epilogue the curtain will descend on the great drama now approaching a close. It will be for the younger generations, the reincarnate souls of those who fell in battle, to inaugurate the work of giving expression, in deathless forms of art, to the vision of that “fairer world” glimpsed now only as by lightning, in a dream.”

That piece in bold italics could apply to a couple of politicians in this contemporary era of ours. One of the reasons why the final paragraph below it also stands out – ‘…It will be for the younger generations…’ – is because there were campaigners flocking to the rapidly-growing Labour Party that tried to do this. One thing overlooked by mainstream popular history – and also the schools history courses in the 1990s, was what this rising Labour Party was campaigning for (see their Speakers’ Handbook of 1923 here) and how this contrasted with their Conservative opponents – in particular on colonialism and relations with both interwar Germany and Russia.

“And the point of all of this is….?”

Trying to find out what history can teach us about the current and future struggle for the future of Cambridge – however you choose to define it. The ‘Build Beautiful’ movement that the former Housing Secretary Michael Gove tried to harness reflected some of the ongoing culture wars that have their own risks. What can people do to prevent the sorts of ugly, bland, identikit buildings going up without falling down internet wormholes into pools of poisonous politics?

Both the growth of Cambridge and the status of its ancient university within the UK’s Political Establishment means that it is both battlefield and prize – and the prospect of building a second urban centre is potentially one of the biggest of them all. We screwed up with the building of the present guildhall in Market Square because no one could agree on an alternative to Cowles-Voysey’s austere design – for which the Guildhall Clock and the two birds either side are about the only things I like about it.

Above – Sid Moon satirising the guildhall debate. 05 Jan 1935 Cambridge Daily News in the Cambridgeshire Collection

One of the things we don’t see in/around Cambridge is how our lifelong learning / adult education policies are helping educate the public about the basics of architecture, town planning, and democracy – and even economics given that all of these will influence what our city ends up with. That’s assuming the ecology that we all sit within hasn’t crushed us in a climate catastrophe beforehand!

Nice to end on a positive note!

If you are interested in the longer term future of Cambridge, and on what happens at the local democracy meetings where decisions are made, feel free to:

- Follow me on Twitter

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge