Once the final sets of devolution deals are completed, ministers should commission a major evaluation project to see if they are functioning as intended – and if they are not, whether the policy response needs only minor changes or an overhaul of governance nationwide

This follows the publication by the Institute for Government of a report on completing devolution in England

Above – Completing the map by Matthew Fright and Akash Paun (2024) IfG

“This report sets out how the Labour government can ‘complete the map’ of English devolution within this parliament, by establishing new mayors and combined authorities across the half of England left out of the devolution process to date.”

Above – Fright & Paun (2024) p2

If you already agree with the policy of the devolution via Combined Authorities with bespoke negotiated agreements with ministers, then the aim of the IfG paper makes perfect sense. The task of creating sub-regional tiers for local government is incomplete and fragmented. This paper shows how it can be completed. The problem I have is that I was never convinced of the merits of this type of devolution in the first place. That’s not to say the others didn’t have their flaws. Any system that tries to govern people will have that element of ‘herding cats’.

A more critical take on devolution for England from IPPR North from February 2020 – this needs re-publicising

The report by Luke Raikes for IPPR North in February 2020 here inevitably got lost in the pandemic outbreak that led to the first of several unprecedented lockdowns. There was no way he or anyone else could have predicted with reasonable accuracy where we would be four and a half years later having chewed up three Prime Ministers, numerous Cabinet Ministers, swathes of junior ministers, and leaving the Conservatives with the smallest percentage of MPs since equal suffrage was brought in back in 1928.

Back in 2016 pre-EU Ref I spoke to Dotty McLeod of BBC Radio Cambridgeshire about my concerns over the proposals for combined authorities for Cambridgeshire, Norfolk and Suffolk. That was in May. Two months earlier ‘The Bookies’ had somehow decided the controversial former Health Secretary Andrew Lansley was ‘the favourite to become Mayor of East Anglia. At which point the people and businesses of Cambridge and Cambridgeshire put their foot down and crushed the whole proposal. It was only granted conditional approval from Cambridge City Council in return for a significant slab of funding from central government to pay for a new generation of much-needed council houses.

The thing is, no one ever made the sound principled case for Combined Authorities as a concept, let alone at a level high enough in the public’s consciousness for it to go beyond the small group of politics’ obsessives like me. It’s not like there was this huge grassroots movement for such institutions to be created. Even then, the Cambridgeshire and Peterborough one can hardly be considered a success, even though thankfully it’s now out of the danger area with its Best Value notice now removed.

If anything, the combined authority model showed how weak it is when imposed on a wide geographical area that has different economic, political, and social cultures that don’t sit easily side-by-side. The EU Referendum demonstrated the polarisation. Cambridge residents voted 74% Remain, while 40 miles to the north in the same county, the people of Fenland voted 75% Leave.

“Were there any alternatives to Combined Authorities?”

Yes. The problem was that no serious attempt was made to develop/flesh them out as serious alternatives to what was effectively the Greater Manchester Model (a Combined Authority Mayor with no directly-elected assembly – noting London has the London Assembly). Furthermore, the whole process of creating the combined authorities was very top-down as Mr Raikes points out.

“The major issue with combined authorities, however, has been the process of ‘devolution’ itself. Devolution has been a centralised process, undertaken at the discretion of individual ministers who make specific demands (such as requiring directly elected mayors) or use ‘unwritten rules’ to maintain control of the process.”

He continues…

“But this process has also undermined the democratic legitimacy of local government itself, as well as overriding the interests of local areas. The process has not been transparent to many of the wider stakeholders involved, such as councillors, civil society, trade unions and businesses – let alone the public, who have been almost entirely excluded from consideration.”

Above – IPPR-N (2020) p23 / p25pdf

Mr Raikes ends his introduction section with this statement – which I concur:

“And while the current process of devolution is deeply flawed, a better alternative can and should be developed.”

Tony Blair and Gordon Brown’s record.

In principle it should have worked. Nine English regions each broadly matching European regions so as to make applying for EU development funding, had their own:

- Government Office (which were the regional offices for central government departments across England – and staffed by civil servants)

- Regional Development Agency (the primary means of distributing that EU funding

- Regional Assembly – made up of a selection of councillors from component local councils

By 2004 the institutions had sufficiently matured enough for Tony Blair and John Prescott to judge that this was the time for the indirectly-elected assemblies to become directly-elected ones. And they put this out to a referendum in November of that year. The rest is history. The Government took a kicking, and it was also a lesson that David Cameron would ignore at his peril when it came to referenda.

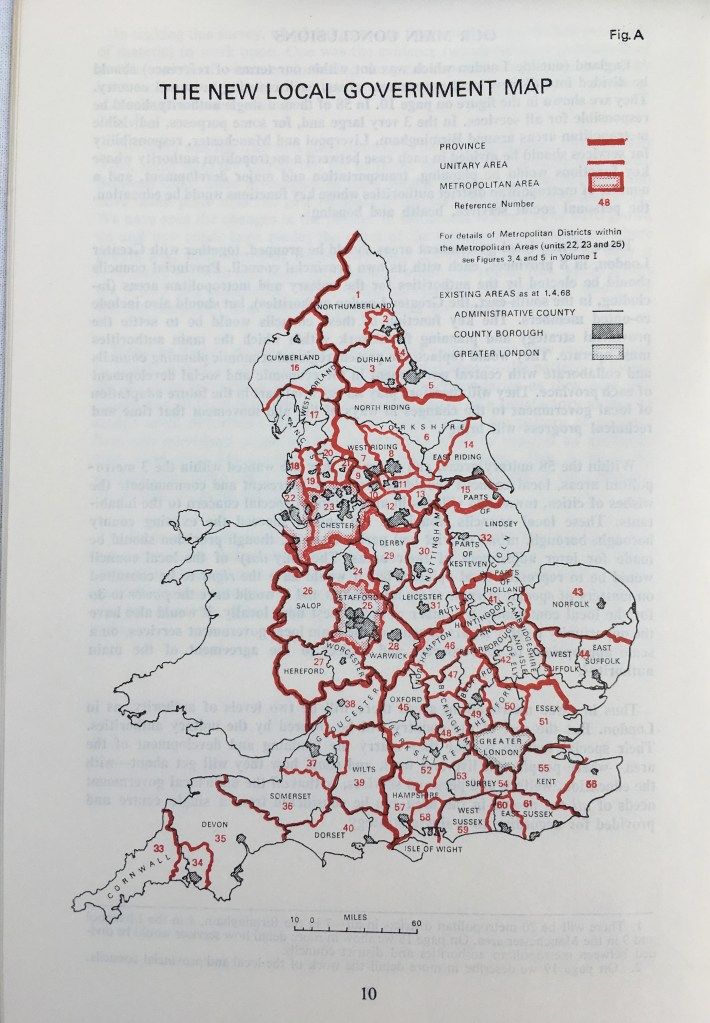

Prior to that attempt was Lord Redcliffe Maud’s Royal Commission 1966-69, possibly the most in-depth study of local government in England in our history. It deserves to have a much higher profile in local government policy circles today

Below – the contents of the summary report, and the map showing the unitary councils and proposed new regions – both of which were scrapped by Sir Edward Heath’s incoming government.

Above – from Lord Recliffe-Maud’s Royal Commission on Local Government in England 1966-69, summary report

If you’re a hardcore policy-wonk you can see the full report and the research appendices here – noting that the House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs called for ‘Redcliffe-Maud 2’ on overhauling the governance structures of England.

The failures of these regional structures in the mid-2000s led to a sub-national review. Mr Raikes again below

“…the regional tier in England has never been fully embedded. The subnational review developed this thinking, and, with the resurgence of the cities agenda globally, the subregional tier emerged as important and the legal entity of the combined authority was introduced”

Above – IPPR-N (2020) p24 / p26pdf

Mr Raikes also picks out the centralising tendencies of the Conservatives in Government – noting the hit local councils took in austerity along with the transfer of accountability functions of schools from councillors to MPs – the latter ***voting to make more work for themselves*** given the constituency casework involved. (Had schools stayed in local authority control, such correspondence could have been delegated to elected councillors in the first instant).

“Which tiers of government / the state should do what?”

Mr Raikes picks up on this too when looking at comparators abroad.

Above – Raikes citing OECD UCLG 2016

I looked up the above reference and found the report here that compares countries and their different levels of investment at ‘sub-national government’ levels

Above – OECD / UCLG (2016) p36 / p38 pdf

Note the chart shows the UK’s sub-national government share of investment being at just over 35% of total public expenditure (With a GDP per capita USD 40,000). Compare that with Germany and the Netherlands that have both higher GDP per capita *and* higher percentages of public investment being spent at sub-national levels. Note for the UK we have highly unequal devolution as far as the nations are concerned – England making up nearly 85% of the UK’s population.

A constitutional convention?

That’s what the IPPR-N paper by Mr Raikes recommends.

“We have drawn on the experience of other countries and set out what a coherent and inclusive programme of devolution could look like. The next step is now clear: a Convention on Devolution in England needs to take place as a matter of urgency, so that the citizens of England can have a say in how they are governed.”

Above – IPPR-N (2020) p60 / p62pdf

A Convention on Devolution in England as a future step? Yes. The next step? Absolutely not. The simple reason being that the public does not know nearly enough about the essentials of politics and democracy to be thrown into such an intense exercise as this.

The importance of citizenship and civics education

For such an exercise to be successful, a critical mass of people have to be knowledgeable about what is being debated and decided upon. The Republic of Ireland amongst other countries have demonstrated *how* this might be done, but it’s worth remembering that the Republic of Ireland only has a population of just over 5million. The population of England is over ten times that. Therefore it’s not simply a case of taking a model for a mid-sized EU country and applying it to the UK which made a complete hash of the EU Referendum debate – just as the Tories in government made a complete hash of the aftermath as well.

It’s worth looking at the detailed recommendations from section 5 from p50 in the IPPR-N Report.

I’m not going to copy-and-paste it all out word-for-word. The policies speak for themselves. The failures of institutions in and around Cambridge to take the people with them over new transport infrastructure shows what happens when controversial policies such as congestion charging are thrown at an unsuspecting population in an era of low trust in political institutions and politicians.

A constitutional convention would require a significant lead-in time. Furthermore, it might require some cultural changes in the workplace – and concessions from and co-operation from employers too. Especially in a society with long hours, low pay, and high living costs. Where will people with multiple work and caring commitments find the time?

That gives the present government the present term of office to overhaul and revamp adult education to incorporate civics, significantly raise the profile of democracy and citizenship education in schools, further education, and higher education – and embark on a longer term culture change to prepare the public for such a national convention.

You could say there is a foreign policy ‘soft power’ objective in leaning on higher education institutions to have core modules on democracy and ethics for all of their students – controversial as this might be. This isn’t just about the stereotype of ‘teaching the offspring of super-rich dictators from foreign lands’, but rather educating new generations of undergraduates, a critical mass of which will end up working in professional services in international environments where sound ethics and the profit incentive often clash. Just look at the record of big oil companies and tobacco firms over the past century.

It does not need to be a standalone policy either. Given the issues with social media, AI, and mis/disinformation, there is no reason why such policies could not be co-ordinated with each other. But for new devolution structures to be successful in England, the creation of new devolved institutions won’t be the end of it. It’ll be just the beginning.

Food for thought?

If you are interested in the longer term future of Cambridge, and on what happens at the local democracy meetings where decisions are made, feel free to:

- Follow me on BSky <- A critical mass of public policy people seem to have moved here

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge.

Below: Feel you don’t know enough about the essentials of politics and democracy? Get yourself a book about politics, democracy, and citizenship in the UK that’s aimed at teenagers such as GCSE text books (or the shorter revision guides).

You can get copies of past syllabuses (i.e. from when the UK was still in the EU – so the rights we lost are covered, for under £5)