John Elledge asks: Why do so many British towns basically suck?. Shortly before the re-post of that article, the House of Lords Built Environment Committee published its report on the future of UK High Streets. And the scenario to avoid? Coming up in any future editions/volumes of Crap Towns UK.

Because when the first edition of Crap Towns was published back in 2003 (over 20 years ago!), there was uproar and outrage. Not from the residents of those places that had been included in the list of 50 towns, but from the residents of those places that were *not included* on the list! Hence why the creators of the list swiftly published a second volume the following year! (Luton, followed by Windsor in second place incurring the wrath of the public – for very different reasons). Fast forward to general election year 2019 and Peterborough found itself on the list – now curated by another organisation, for the wrong reasons.

“Why do so many of our urban settlements (for want of another term of the places we live in close proximity to each other irrespective of size) get criticised so much?”

The first thing to make clear is that there was no ‘golden age’ where everything was splendid. A quick browse through the British Newspaper Archive on any settlement of your choice will throw up various crises in the time period it has digitised newspaper copies of. Furthermore, you will also find tales of incredible resilience, campaigning, courage, and sheer persistence from people and communities as they strove to improve where they lived.

Mr Elledge’s article takes an interesting look at the historic county town of Bedford, and the much-maligned towns of Luton and also Milton Keynes nearby. (See the trio on G-Maps here)

Rather than get into a non-debate about the shortcomings of places I know little about, the wider issue for me is the role of collaborative regional planning – one of the few political issues that divides Labour and the Conservatives. Historically Labour governments have created and promoted regional structures, while Conservatives have diminished or abolished them. This year the pendulum swung back towards pro-regional planning with the general election result back in July.

House of Lords Recommendations on high streets in a post-mass retail age

You can read the reports via the landing page here

Above – House of Lords Built Environment Committee 2024/25 – High Streets: Life beyond retail?

One of the contributors to this piece was Vicky Payne who co-authored High Street – How our town centres can bounce back from the retail crisis (2023) – expect to see several of the recommendations from this book in the report

The list of recommendations is ***huge*** – which reflect how complex the policy area is: there are so many different factors that affect the life of high streets – not least the combinations of national public policy options. (See the summary list here)

“Which policy recommendations and/or statements from their Lord-and-Baroness-ships stand out?”

They break the 48 paragraphs into themes:

- Considerations for the modern high street

- Responsibility for the high street

- Policy levers available (which parts of government can do what?)

- Funding – who pays for what?

Taking each theme in turn:

Considerations

A high street can be both a geographical location *and* a reflection of a large part of the ongoing collective activities of the people who make up a particular settlement, district, neighbourhood. That means it’s not fixed. It’s metaphorically living, breathing, and changing over time. Sometimes the changes will be slow and gradual. Other times they will be dramatic. (Whether part of a comprehensive development plan or the need to rebuild after devastating war).

Access is paramount because the majority of the people who use a high street don’t necessarily live there. The larger the high street and settlement, the greater the distances people will be prepared to travel – assuming that there are services and facilities on said high street that are not available elsewhere.

Access does not just mean travelling. It also means facilities to meet the needs of as many people dependent on the collective offer of a high street as possible. This includes but is not limited to:

- Banking facilities

- Health and safety (in response to higher levels of pollution and crime)

- Public health – eg public toilets and conveniences

- Creating a place where people would choose to be in/at ahead of other places

- Having a high street that meets the needs and wants of the many, not just the few

Who is responsible for the high street?

Everyone and no one at the same time. In the times before the development of the railway and telegraph – and later modern roads and telecommunications, towns and cities had to be decentralised by their very nature. Micromanagement from a distant centre was impossible. Hence the rise of self-governing towns that were able to negotiate with the monarch (in the case of England) where in return for contributions to the royal coffers, the monarch would grant charters which amongst other things enabled the town’s authorities to tax passing river trade, or wagons going to market that needed to cross the bridge over the Cam. (See Prof Helen Cam’s summary in her epic contribution for the Victoria County History edition for Cambridge town here)

What we have now is something far, far more complex – not least because in the UK, our national system of government is based on the core principle of a Sovereign Parliament.

Within the United Kingdom, Parliament is Sovereign. It can do whatever it wants and can legislate on whatever it wants. (That’s not the same as getting what it wants, nor does it mean that its actions are free of negative consequences or unforeseen side effects!)

Harold Laski’s local government tome A Century of Municipal Progress 1835-1935 charts the 100 years since the Municipal Corporations Act 1835 – the Act of Parliament that amongst other things created the statutory/legal basis for the re-establishment of Cambridge Borough Council (amongst many others) and laying the foundations for modern local government that we are familiar with today. With contributions from many of the great and the good men (depressingly no women were included as article contributors despite a critical mass of them more than capable – including Clara Rackham and Florence Ada Keynes from Cambridge Borough Council), the final one contains a chronological table that lists each Act of Parliament that either granted new powers for, or imposed duties on local government in the governance of villages, towns and cities.

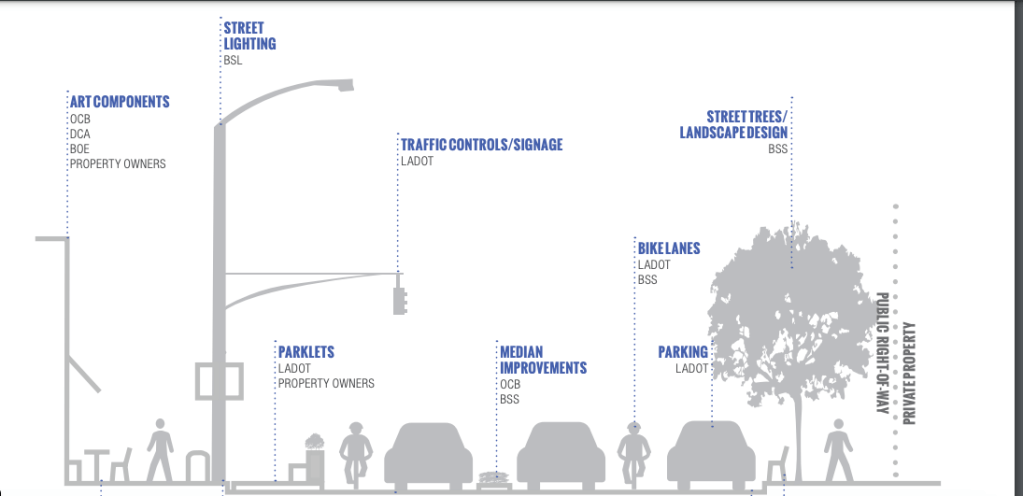

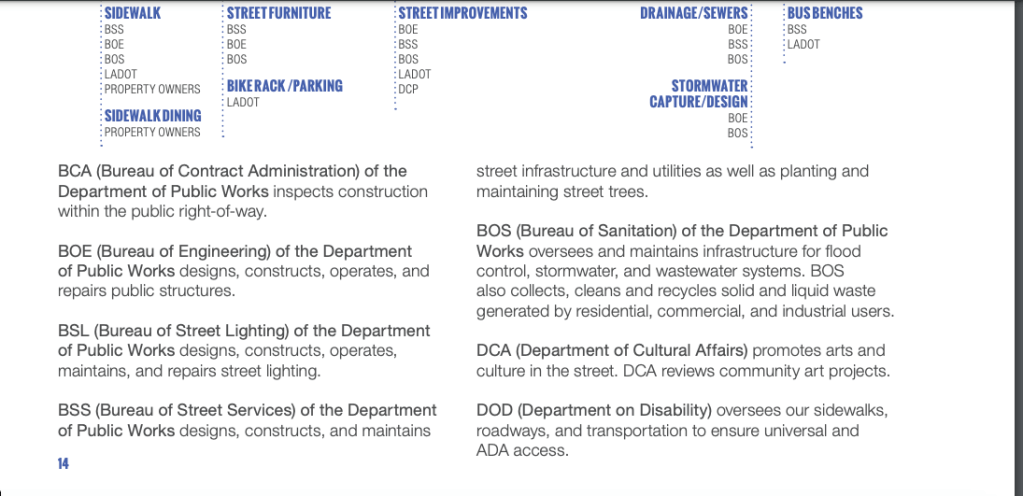

Los Angeles – a quick case study of who does what with streets

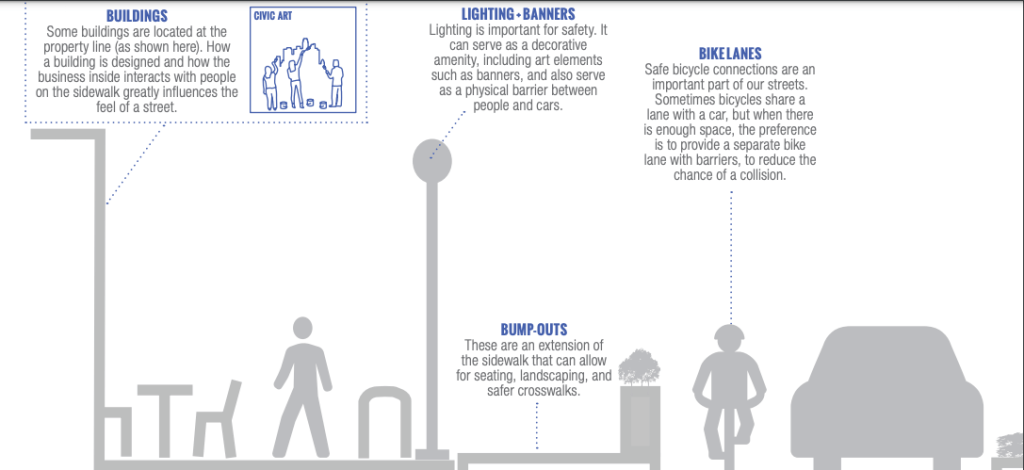

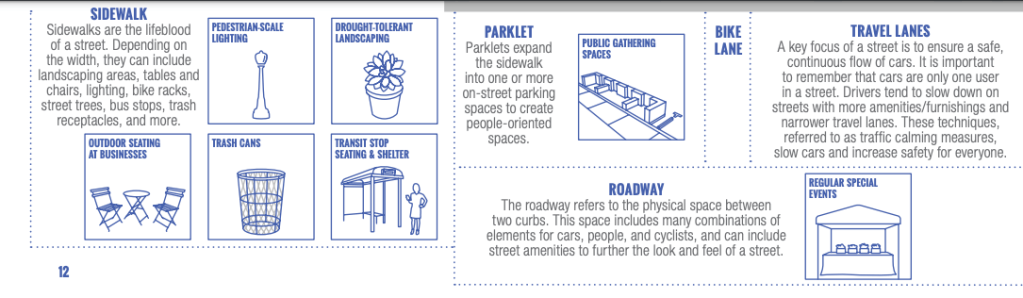

I stumbled across this by Hayden Clarkin from via Jarred Walker’s social media accounts. If we take some diagrams from the Los Angeles DIY Guide to Great Streets (2017) we could create UK equivalents (noting local government is a devolved matter outside England) and identify which Act of Parliament designated which tier of the state or private sector is responsible for which piece of civic infrastructure. In terms of who is responsible for what on an English street scene similar to the ones below, what would they look like?

Above – Los Angeles DIY Great Streets (2017) p14

Note it gets even more complicated when you add the utilities:

- Mains gas

- Electricity

- Telecommunications/broadband

- Water and Sewage

- District heating if applicable

…and so on. In the UK’s case, the catastrophic privatisations and following regulatory and policy failures by successive governments resulted in a combination of underinvestment, asset stripping, companies loaded with debt in complex structures, rotating doors from boardrooms to regulators and back, and huge salaries and bonuses for executives.

Above – Los Angeles (2017) p12

This reflects why the English Devolution White Paper expected in the first week of December 2024 will be ever so important – if they get the policies right!

One of the reasons why national politicians – especially ministers and shadow ministers are moving towards the concept of combined authority mayors is because it enables them to tell the public to speak to their combined authority mayor about whatever the local issue is – without having to worry about the mess that is local government in England, which has been left in the ‘too difficult to deal with’ pile by successive governments for too long.

My main concern is that local government in England does not have the powers, resources, or internal capacity/expertise to carry out what the public wants them to on improving their town centres.

Policy levers and options available

This section from paragraph 19 of the summary feels a little messy and disjointed. This needed breaking down into further sections such as:

- Long term development/strategic planning

- Development control (individual planning applications)

- Enforcement functions

- Spending by councils (both capital – ie on new buildings, and revenue – on services)

- Legislative and policy changes required by central government and Parliament

- Landlords and tenants

- Other parts of the state that provide essential services (primary healthcare and libraries for example)

- The role of the voluntary and community sectors – wider civic society

Who stumps up how much money?

…and what should it be spent on? This comes back down to the too difficult to deal with issue of Local Government Finance. Part of the problem is our system of taxation doesn’t make it easy for people to see where tax revenues go or what they get spent on. Instead, what the Conservatives both in majority and coalition governments have delivered are higher council tax bills alongside huge declines in service delivery – to the extent the public can see it visibly. That was a decision by George Osborne and Eric Pickles – approved by the Parliament of 2010-15, and then the succession of PMs, Chancellors, and Local Government Secretaries to push through with catastrophic austerity policies with no ‘safety valve’ other than local council tax referenda challenging councils to go to their electors to increase council tax bills disproportionately on the poorest in order to maintain services. Only the Green Party in Brighton were brave/foolish enough to try and go to local referendums but failed to get anywhere with the moves.

In Cambridge where inequalities are huge – not just in wealth and income but in terms of access to and influencing national policy-makers, we have been told on what feels like on an almost daily basis of the economic success of the city while at the same time having to deal with budget and service cuts every year from city and county councils. That brings Politics into disrepute and the ministers responsible for bringing in such systems and maintaining them in the face of the implosion of so many towns and cities must bear responsibility for where we are now.

On a slightly better side the announcements from ministers indicate they are coming round to the view that major overhauls of structures and systems are needed. The risk inevitably is that poorly-formulated policies and ‘regulatory capture’ by powerful interest groups ends up having the opposite impact of what ministers desire. eg Developers paying lip service to policies and requirements brought in to deal with the climate emergency. We know that’s what they’ve been doing for the past couple of decades because the construction industry was exposed at the Grenfell Inquiry of doing exactly this. How many of the buildings constructed over that time period would meet the design and regulatory requirements / performance standards of the time they were built? Eg on energy efficiency. How many rental properties would face being shut down because of things like dangerous levels of mould?

Local government currently does not have the capacity to do what ministers are asking them to do, and building up that expertise and capacity won’t happen overnight

Which means there’s a huge risk of a consultancy bonanza for the usual bidders. Far better then for ministers to prioritise dealing with the capacity issues in local government first – which also means having suitable adult education and skills policies in place to enable councils to train up their own staff and build an internal capacity and corporate memory from which to work with.

Part of that capacity also includes a remit to influence what public services are located where – even ones not provided by local government, such as hospitals.

Local councils have no powers to tell NHS organisations and contractors where specific clinics must go. The underfunding of doctors and dentists surgeries exacerbates the situation for residents. They see the houses being built, but not the essential healthcare services amongst other public service infrastructure coming in alongside. They see developer contributions going towards some parts of the city but not others. On top of all of that, and perhaps understandable in this politically toxic age of ours, there is no social means for people to find out the essentials of how our systems function and malfunction unless they are ***really, really motivated***. Far easier to turn towards a more extreme candidate who shows up from out of the blue who makes extravagant promises at the expense of whichever section of society the print press bosses happen to be hating on at the time. (What is the percentage of BBC Question Time episodes that have featured an immigration-related topic over the past quarter of a century and what impact have all of those broadcasts had on coming to a reasonable and workable set of policies that resolve both symptoms and root causes? Oh).

There are inevitably a host of things that will be outside the remit of the Lords’ report

The extractive economy – landlords charging tenants of flats and business premises very high rents that reduce their disposable incomes that might otherwise be spent locally is but one example. The failure to prevent corporate tax avoidance, the failures to rein in the Crown dependencies and overseas territories that are tax havens. The failures to rein in executive pay vs lowest paid workers (See Locality here, and the Equality Trust here). The failure to ensure that developers pay for the full costs of council town planning services – especially for large developments rather than hitting the council tax payer. (The Government is consulting on making town planning services cost-recovering in the face of a chronic shortage of town planners – but what they need to do is fund a new generation of town planning courses inclusive of maintenance bursaries, as with other skills sectors with similar shortages).

It’s a beast of a blogpost but that gives some insight into the complexity and the huge financial interests that influence what might otherwise seem like a highly localised issue.

If you are interested in the longer term future of Cambridge, and on what happens at the local democracy meetings where decisions are made, feel free to:

- Follow me on BSky <- A critical mass of public policy people seem to have moved here (and we could do with more local Cambridge/Cambs people on there!)

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge.