A stream of articles have been published this month about the state of our town centres. How festive did your one look this year? (And does Waterford’s Winterval do a much better job?)

Despite the handful of carols at last weekend’s Christmas Cocktail concerts I sang in as part of We Are Sound, I’ve hardly noticed the time of year beyond the few cold snaps. The only time I can recall Whammageddon was when a random doom-scrolling session popped up with Emilia Clarke’s version. From 2019. Which I had completely missed – presumably because I was distracted by the general election of that year.

Cambridge BID sponsoring/paying for Christmas lights

Personally I prefer the old-fashioned system of taxing firms properly and allocating funds for civic-pride-related things. But Cambridge BID’s setup is what successive governments have given us as a sop to the years of austerity. At least we’ve got something – other places have got nothing. And it feels (to me at least) that national public holidays that are also significant religious festivals (in the case of the UK, Church-based given the Established Church of England) have to be large and collective or they are nothing. But how can something be large and collective in fragmented societies with high turnovers of population barely held together by resource-poor local councils and a withering civil society sector struggling to recover from a once-in-a-century global pandemic?

Between the headlines are a series of even greater challenges

Which makes the headlines and the articles below all the more striking – not just because of the decline in retail, but also because amongst other things it follows the decline of longstanding community institutions throughout the late 20th Century in the face of Thatcher’s huge economic and social policies.

- Christmas cannot save the high street (New Statesman)

- ‘Town centre isn’t going back to historic times‘(BBC Staffordshire)

- Can Christmas save Britain’s high streets? (The Big Issue)

- Bringing declining high streets back to life (The Guardian)

- High Streets – Life beyond retail? (House of Lords Built Environment Committee)

At the same time, I can’t ignore the impact that online shopping has had on town centres – the impact of which public policy failed to keep up with.

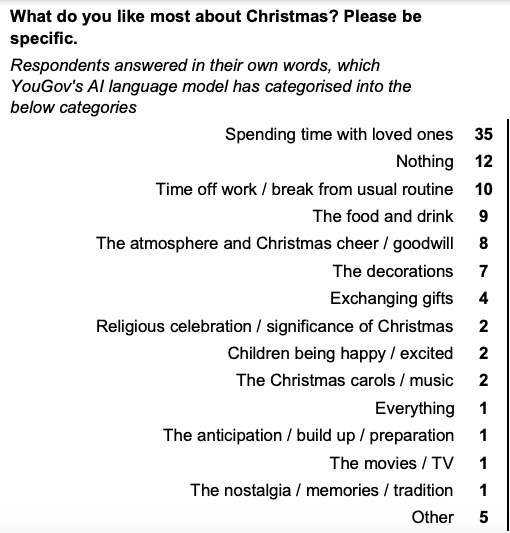

What YouGov surveys said about Christmas 2024

You can see the fieldwork here

Above – for a major religious festival, only 2% of respondents put religion as the aspect they liked the most. (At the same time, it didn’t register as something people liked *the least* – eg having to go to church and enjoy/endure an extensive lecture from the pulpit!)

“How was Christmas meant to save high streets anyway?”

It’s a reference to people going shopping – historically that’s when shops and retailers make a large proportion of their sales. Not surprisingly as UK cities have become more diverse over the decades, some retailers have started targeting other religious festivals in order to encourage people to spend. Basically the market researchers spotted the dates in calendars featuring cultural/religious festivals that involve a tradition of giving gifts, found out where there are a critical mass of people who celebrate them, and responded accordingly.

Above – from IWOCA survey on small businesses & Christmas sales

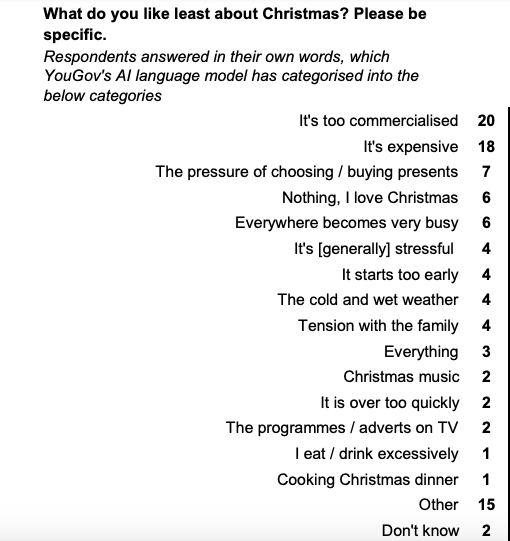

Given the pressures to make sales during this time of year (and the marketing response), not surprisingly the sentiment that the festival has become too commercialised/expensive is reflected in the survey results from YouGov. That complaint is not a new one – the British Newspaper Archive has entries going back over a hundred years which complain of the commercialisation of Christmas.

Furthermore, anecdotally the early new year is also when firms are more likely to go into administration/close because there’s more cash in the bank and less stock to dispose of if a lender is worried about firms remaining viable concerns. The first quarter of any year is the one to watch for on business and retail insolvencies.

Short term boosts seldom sort out underlying structural problems

In an era of online shopping and hollowed-out town centres, even if people wanted to go to ‘the shops’, the choices available is far fewer in both range and number compared with previous generations. The failure of successive governments to ensure a balance between high street and online retailers has inevitably contributed. At the same time, the rise of Air BnB and the failures again of the state to regulate rapidly-emerging business practices inevitably changes where flows of wealth go. Homes built either as council housing or as for private sale to owner/occupiers that end up on Air BnB listings are dwellings that case supporting residents who invest time and money in their local communities.

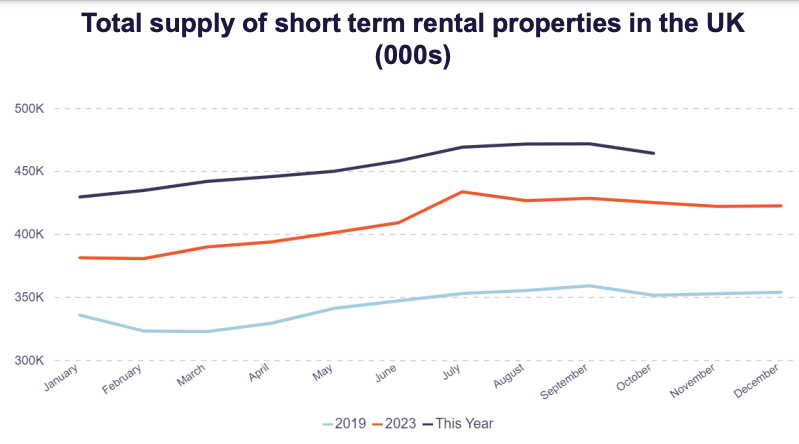

It’s worth noting that year-on-year the number of Air BnB-type properties going on the market is rising according to the British Tourist Authority/Visit Britain.

Above – BTA/Visit Britain Oct 2024

What’s not clear is the breakdown of bespoke-build (‘apart-hotels’) to conversions of previously residential housing. Furthermore it does not show the distribution, which inevitably is focussed on a minority of places rather than equally spread. Yet we already know that second/underused homes and Air BnB accommodation have an impact in tourist hotspots because ministers have indicated they will be bringing in new controls similar to those consulted on by the previous government here.

Again, the phenomenon of ownership and tenure of housing having a negative impact on residential communities is not new. The issue of universities expanding student numbers and relying on local housing markets to house the students is a longstanding – see this from 2009.

Destabilised communities can’t save town centres any more than they can save ‘Christmas’ and the church institutions associated with it.

I was going to write some more on the latest scandal involving the Established Church but thought better of it (even though it’s one of the news headlines for today). Yet one of the longer term pieces of research that came up was from data in the British Social Attitudes Survey of 2015.

Above – No Religion (2017), p13

It reminded me of what Rowan Williams, the Cambridge-educated former Archbishop of Canterbury who returned here on his retirement said in 2014 about the UK being a post-Christian society.

“If I say that this is a post-Christian nation, that doesn’t mean necessarily non-Christian. It means the cultural memory is still quite strongly Christian… But it is post-Christian in the sense that habitual practice [i.e. going to church on Sunday] for most of the population is not taken for granted.”

There’s further reading from the University of Kent on the 2017 report as part of a wider research programme Understanding unbelief.

From a ‘saving town centres’ perspective, there’s a research strand on the reuse of old buildings by changing communities – as well as some lessons to be learnt for the construction of new towns. But I’ll save that for the future.

Merry Christmas from me and Puffles!