From the personal to the public policy perspective, on how conversational and interactive social media covering both local news and interesting topics seems to have been replaced by zombified AI-driven doom-scrolling

Musician Ellie Dixon whose music career I’ve been following for over a decade since one of her first performances at The Junction in Cambridge has put out this clip for her up-coming single Guts.

Which resonates with my experiences of the 1990s for a whole host of anxiety-related reasons made worse by what we were being told (or not allowed to discuss) at school and church being utterly inconsistent with the reality of the world we were growing up in as teenagers. I started secondary school in the early 1990s, only a few years after the toxic Section 28 had been brought in by Margaret Thatcher’s Government. The additional complication I had to deal with was being a very visible minority in a South Cambridge that socially has changed quite significantly since then. It’s something I never processed at the time, haven’t done since, and probably never will. It’s too late. Best leave sleeping dragons be.

Ellie says in her piece that even as a pop artist she never could relate to ‘pop culture’. It was similar with me in the 1990s – because with the most prominent areas of culture – pop music and football in my case, there wasn’t anyone prominent who I could relate to.

In my later teens one of the big problems of the era was alcohol-fuelled casual street violence – which in the early 2000s looked something like this. Since then, a concerted effort by the state has shown some interesting results – including a substantial fall in the number of teenagers having had their first drink by the age of 15. But it was that fear of violence and my inability to deal with it that (with an anxious disposition similar to what Ellie described) often stopped me from going out and about – especially at university, where I didn’t like the nightclub culture. The problem was that I had been put off by classical music so much that I never sought to find something new until I finished university.

That dislike of classical music was driven by a local institutional musical culture which in itself was hostile to popular music. It reflected the institutional middle class social insecurities of that era. The message I got was that working class boys were allowed to play football, but middle class boys like me had to go to church and do our violin practice and then do exams (even though all I wanted to do at primary school & early secondary school was to play football!). Given that my generation was ‘the last of the ignorant’ – ie the last to go to school in an era without the internet, I’ve often wondered what impact web access would have had on us in terms of simply being made aware of the opportunities that might have been available to us. And what could have emerged from it.

Which is why in the decades since I’ve been interested in on some of the formal research on why teenagers ‘give up’ playing musical instruments (see Survival of musical activities. When do young people stop making music? (2021) by Ruth & Muuellensiefen, and also Dr Anna Bull’s book which I wrote about here). This has also come back as a party political issue due to the underfunding of the arts and the dominance of the sector by people with privately-educated backgrounds.

One of the most recent articles I recall noted how some of the theatres in the most expensive private schools are better than many of the public and municipal theatres that serve wider society. In Cambridge two of the most recent private school facilities (that have some but limited public access) include The Leys Great Hall – a medium-sized theatre, and The Perse Swimming Pool. It speaks volumes about Cambridge’s growth that despite the social need for new and/or upgraded public performance venues and an additional large public swimming pool, it is the private schools that have been able to raise the money and get them built first.

Combine the social opportunities between the different social classes and we also see something similar reflected with adults – as Sam Freedman noted here.

Now consider how a number of large civic events have been collapsing like skittles in Cambridge of late – public events so large that they attract and serve an audience far beyond the city boundary – the Cambridge Folk Festival 2025 being the latest.

“This is incredibly disappointing for such a loved and long established event, for which people travel from miles away and adds to the culture of Cambridge. It follows the council’s earlier ditching of the Big Weekend.”

Cllr Cheney Payne (Lib Dems – Castle) to BBC Cambridgeshire. 17 Jan 2025

It’s easy to forget the amount of preparation and rehearsing that goes into shows that are part of such large events. The previous target event and date to work towards is no longer there – and that has an impact on community groups participating.

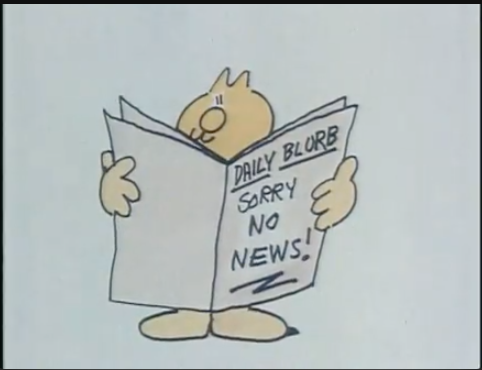

The implosion of conversational social media

“What do you do when changes by social media platforms cut off your means of conversations?“ I asked this time last year.

One of the benefits of earlier conversational social media was the ability of communities of interest to find each other. This has been hugely beneficial in the area of medical research when we look at all things neurodiversity and mental health. In particular, it has forced the issue on so many things in the world of office work and why some of us who on paper may have lots of qualifications seem to struggle with the most basic of tasks. It was only in the final months of my civil service career that I found a group of people with similar dispositions 15 years ago in what became the UKGovCamp network. But as the big tech platforms moved away from displaying content people consciously chose to see and more towards AI-driven ads and reels, the inevitable results of not being able to keep up with conversations because replies were never displayed routinely and first time, began to have an impact. By the time the first lockdown was brought in, social media (for me at least) had effectively ceased to be.

Combine the decline of conversational social media with (at a local-to-me level in Cambridge) the decline of people reporting on, and commenting publicly on developments in local democracy and we find ourselves in the midst of a perfect storm: Just when we need regional and local media – mainstream and social, to be at their strongest, we find the very opposite.

One of the other impacts of the decline of conversational social media is that my awareness of other people’s perspectives and life experiences inevitably declines. I can try to stay aware of issues that other parts of the city face, for example by reading council reports and newsletters, but that’s not the same as the softer day-to-day interaction with other people who for example might have children at local schools. (Where fighting the educational bureaucracy afflicted by 15 years of austerity & centralisation can become more than a full-time job). Or what the challenges are in the recently-built residential communities whose cohorts are different to my part of town – now a strange and increasingly lifeless mix of an increasingly elderly settled population (that 40 years ago were the young families) facing a growing number of properties bought out by profit-seeking landlords for the short-term-let market that does little positive for community life, the financial benefits being extracted with no opportunity for the properties to be used by people who might want to get involved in community life.)

Moving forward and shaping the future of our city in the face of a broken social media environment

That’s the bit I’m struggling with at the moment. Because thus far no alternative platform has emerged as the place for a critical mass of people in our city to act as that forum for people to debate the issues. Even worse, none of the institutions of the city seem to have the desire or capacity to organise the much-needed offline forums to help keep local residents up to date with who has decided what. That was crystal clear at the East West Rail event where ministerial decision on a southern entrance into Cambridge taken in 2023 was still being contested. (In a nutshell, ministers need to make clear what things are up for debate and what things are not as far as the Bedford-Cambridge section is concerned.)

Whether a new platform will emerge remains to be seen. In one sense there is a strong public interest in UK and EU state actors influencing that by saying that should a suitable one become available with sufficient safeguards and functions, then they will migrate the social media pages away from the current ones and onto new ones – which could be enough to take a critical mass of their populations with them. Whether there is the *Political* will (and unity) to do so, is another question!

If you are interested in the longer term future of Cambridge, and on what happens at the local democracy meetings where decisions are made, feel free to:

- Follow me on BSky <- A critical mass of public policy people seem to have moved here (and we could do with more local Cambridge/Cambs people on there!)

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge.