The RSA (or more precisely, The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce) launched its new season of things with the statement: “How do relationships affect our health, wealth and happiness? Discover the power of connection through our exciting event series”

In his annual lecture (which you can watch here), Andy Haldane, the former Chief Economist at the Bank of England, now the CEO of the RSA explored the concept of social capital and how it has been declining in the USA to see what policy lessons there are here in the UK. If I understood him correctly, in March 2025 the RSA will be publishing a new piece of research on social capital in the UK based on number-crunching some monster data sets including those held by a few of the big tech firms.

TL/DR?

To get us out of the malaise that we are in, it’s not the traditional ‘economic growth’ that will get us out. Rather as Haldane says, it’s reversing the decline in social capital. Environmentalists might add that this should cover natural/environmental capital and involve including policies such as (but not limited to) to stopping the acts of ecocide and reversing the decline in number and varieties of species on our planet.

“How does this apply to Cambridge?”

Let’s take the introduction text from the online video:

“Despite unparalleled global connectivity, communities are fragmenting, leading to slowed economic growth, reduced social mobility, rising loneliness, and declining trust in institutions”

The RSA from Andy Haldane’s intro text on the video, 21 Jan 2025

Cambridge is probably at the most globalised point it will ever be in its history if the climate emergency results in far fewer numbers of people able to travel long distances to visit or migrate. BBC Look East’s Mo Bakshi spotted Emilie Silverwood-Cope’s column in this week’s Cambridge Independent which lampooned the different types of parents you’ll find in 21st Century Cambridge. Note the PhD-parents – the ones who have moved here because one of them is studying for a research degree or post-doctorate, but is unlikely to stick around for beyond that time. It’s a phenomenon that was part of my childhood in primary school where a child from a foreign country might appear at a random time of the year, stick around for a period of six months to two years, then disappear never to be seen again.

Now compare their experiences with those that have moved to the UK from abroad for the long term – for example because a major employer such as Addenbrooke’s Hospital sent out a call all over the world for people to work there. In the 1960s my parents responded to that call and me and my siblings are the result. At the time they were enfranchised because of a mix of ancestry on one side of my family and the then non-independent status of the country where the other side of my family is from. Had I married and settled down, I’d have fallen into the ‘Cambridge Lifers’ category in Emilie Silverwood-Cope’s column that one of my siblings is now in (i.e. the child of the city returning after university), with my parents being in the ‘Grandparents on school pickup duty’ category. I was struck by just how many of the latter were picking up their grandchildren when I was putting up election posters the year before last, compared with my own years at the same primary school back in the 1980s. Far, far more grandparents – and now thinking about it, noticeably more fathers too.

One of the things that also struck me while I was in hospital having conversations with staff during the lockdowns was how our political system froze them out of local decision-making because we don’t have residence-based voting. Scotland changed their laws to enfranchise residents in local and Scottish elections irrespective of nationality back in 2020. I think we should do the same. ‘No taxation without representation’ and all that. Hard to talk about local democracy and politics with people who are frozen out of the system by law and the policies of the political party in power. Even if it’s on things that affect their day-to-day lives.

Private secondary schools, and private language schools

Want to reduce overall social capital? Ensure that you have a set of very exclusive private schools, and ensure that your language schools aimed at the wealthiest of international markets are different worlds to the rest of the children and teenagers in your settlement. This is something that Andy Haldane touched upon here.

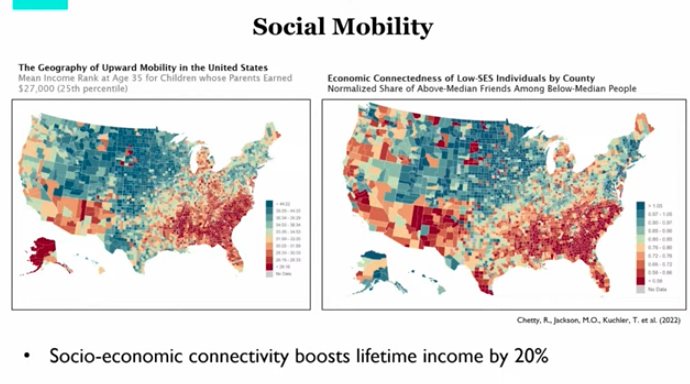

“Perhaps social capital / social connections explains the variations” says Haldane. “It really is who you know, not what you know, for lifelong prospects. He then noted that if you took a child from an economically-deprived background and put them in an affluent background, the lifetime income of the that child would rise by 20%. (He said Rich but I’m sure he meant the opposite, because otherwise the private schools would be far more socially diverse than they are!)

The problem is that such a policy does not solve the structural problems. It simply creates an opportunity for a handful of individuals each year who get the scholarships – and there’s no guarantee that the scholarships available actually go to those in the most financial need. For those of you interested in having a deep historical dive on the private schools’ question, see some of the old policy documents from the mid-20thC here when Harold Wilson’s first government came closest to integrating the private schools into the state system – the Public Schools Commission report of 1968 is important if heavy reading. One of my proposed short-medium term policies as an alternative is to expand the Business Improvement District framework to cover the private schools and language schools, and impose a levy on the fees they charge with the revenues going towards funding new facilities and activities that bring children from all backgrounds together – in particular paying for the participation, transportation, and equipment for state-educated children. Because the situation now is that children from affluent backgrounds from all over the world are making connections with each other in their teens in our city yet in environments that our own city’s teenagers are effectively excluded from.

The vision of Prof Jeremy Sanders of Cambridge University in 2014.

In a document where a host of prominent individuals were invited to write their vision of Cambridge in 2065, Prof Sanders wrote:

“Top people from around the world will still want to gather together to meet and discuss their research and ideas. The University’s unique selling point — its USP — will be its convening power, bringing key individuals to Cambridge to experience personal interactions and chemistry despite the large carbon, cost of international travel in an energy-deprived world. At every level, from undergraduate via graduate student, postdoc and sabbatical professor to top executive and world leader, Cambridge will be one of the key venues to come and be seen, and to rub shoulders with the global intellectual elite. If it sounds like an exclusive conference venue, then that may be about right.”

Sanders, J (2014) in Cambridge 2065, p48

…Which if more people had known about it at the time might have kicked up a storm over the remarks. Now put his remarks in the context of this quotation from a paper from The Lancet in 2022.

“…loneliness is not an illness, but a feature of urban planning and societal systems that have not prioritised people’s health and social needs.”

Above – Feng, Astell-Burt (2022) Lonelygenic Environments, The Lancet

How does turning Cambridge into a global exclusive conference centre for the wealthy to ‘rub shoulders with the global intellectual elite’ meet the needs of the people of Cambridge?

Comments on a postcard please.

“Cambridge’s culture of learning – and its institutions of learning feel fragmented, discrete, and siloed.”

I wrote the above in July 2023 and by the feel of things I’ve got bored of waiting for the Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Combined Authority to do something about it – hence all of my recent questions about lifelong learning and adult education colleges. Have a listen to my question about whether the CPCA had held any meetings with the sci-tech park firms and landowners about building new lifelong learning colleges.

Was the question answered? Yes or no?

It’s not just on the vocational skills policy area – although the Political Class has this as a priority. What successive governments did was to combine funding for leisure and recreational courses with that of basic and vocational skills for adults, cut them both, and then prioritise the resources left over for the latter. Which is why our once thriving recreational and learning for leisure sector is so utterly enfeebled in comparison today.

Again in a previous blogpost, I looked at the case of classical music-making.

“For a city as endowed in classical music as Cambridge is, it’s soul-destroying that we don’t have anything like those set ups here. We should have a late-starters’ orchestra like East London does. We don’t. …What is the pathway for anyone wanting to learn as an adult to progress into joining a group like the Cambridge Philharmonic? That’s not something that either a local council or a single music group can solve alone. That’s a city-wide, even county-wide issue.”

Above – The Mary Ward Centre in London, where I briefly played the viola during my Whitehall days when I lived not far from the venue

A city like Cambridge should be able to recreate an equivalent of the Mary Ward Centre. We have the collective wealth within the city and economic sub-region, we have the musical talent to provide the teaching and inspiration, but we do not have the institutional infrastructure or the institutions with the right morals and values to get such a centre established. If we did, we’d have established lifelong learning centres to meet the chronic skills shortages the sci-tech sectors keep on complaining about (but doing precious little in terms of actions and funding provision to resolve).

As for the response from the Combined Authority itself, either it hasn’t been paying attention to the public questions I have been putting to them over the past few years, or as an institution it lacks the imagination to go far beyond what central government policy is, preferring (perhaps understandably after the years of party political instability locally and nationally) to stay within the safety of its funding agreements with Whitehall.

It cannot stay that way – nor will it. The Government’s White Paper on English Devolution has confirmed that. The new powers and responsibilities, combined with the new generation of unitary councils I hope will force the issues even if the up-and-coming Mayoral and County Council elections in May (just over three months time!) don’t do so before hand.

“What were Mr Haldane’s recommendations?”

He called for a comprehensive, cross-cutting national programme to respond to the crisis of social cohesion and declining social capital – a crisis defined by:

- Stalled social mobility (think public school domination of the performing arts)

- Low growth (can the Political Class see beyond the narrow lens of GDP – which Mr Haldane also challenges)

- Epidemic in loneliness – hello! Welcome to my world! (Note this from The Lancet in December 2022 – how does it read two years later?)

- Crumbling communities (as reflected by high streets across the country)

His call was for a new economic policy that went beyond traditional economics and encompassed society on the grounds that as the above-points show, the collective deep malaise is social (and I also say environmental) as well as economic.

“What might that national programme involve?”

In one of his final sldes, Mr Haldane covered the following:

- Data and evaluation – it’s not an area of the civil service you become aware of until you work inside the system (but even then it’s up to ministers and political advisers to be competent enough in making use of the evidence that makes a difference)

- Education and learning – Mr Haldane says we must rethink access and exclusion criteria as well as the content of the curriculum. (The latter is already in progress – but I’d go beyond that to ask where adults can learn about the things that either had not been invented when they were at school, or because institutions banned them from learning about such things (see Section 28, but think also about law, religion, values of parents etc).

- Housing and planning – there’s some really interesting researching being done on how architecture and the built environment affects not just our physical but mental health (See also The Happy Design Toolkit by Ben Channon) and in particular moving towards models of sociable living and co-housing rather than cramped little rabbit hutches for each one of us (Think a large shared park vs the large space broken up into tiny, fenced off plots each with your own under-used lawn-mower to mow it).

- Business and employment – new models of corporate governance and ethics

- Social infrastructure – from the hard (public realm, sports centres, arts centres) to the soft (social prescribing)

- Media and communications – a revamped role for public broadcasting?

Mr Haldane could go much, much further with this if he wanted to.

Let’s go back to Sir William Beveridge’s report – and the five giants below:

Above – The Struggle for Democracy 1944, p35

If Mr Haldane’s and the RSA’s research is to become as epic as Beveridge’s report was, how much more ground would it need to cover?

For me the big one is environmental

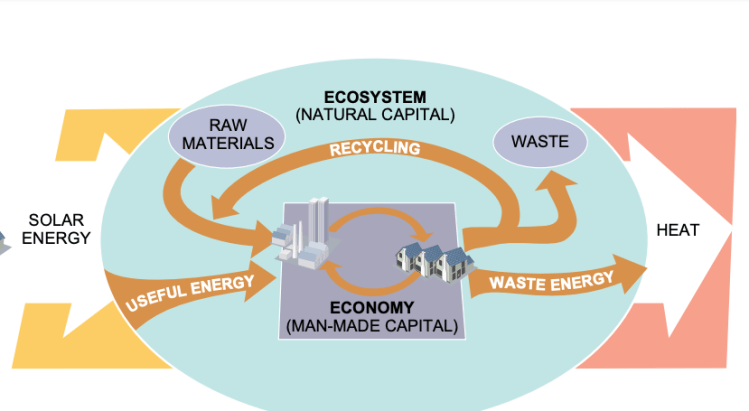

With that in mind it could involve working with the Circular Economy model and Doughnut Economics movement led by Kate Raworth and co. In particular one that puts the economy within an ecosystem – a concept I first came across a quarter of a century ago in an article by Prof Herman Daly, and which has influenced my thinking ever since.

Above – From Daly (1993) The Perils of Free Trade (Scientific American).

What I really like about the diagram above is that it compels the reader to account for raw material extraction, waste, and recycling. Furthermore it makes it hard to avoid the challenge of ensuring economic functions are sustainable – in that they do not degrade the living standards and the ecological health of future generations. This then means they have to consider policies that internalise all of the costs of production – the things that opponents often call ‘red tape. Levels of output and types of output can change significantly – as the planet found out with the CFCs crisis in the 1980s and also with leaded petrol. (Need a reminder? Get hold of an old copy of the Blue Peter Green Book)

Food for thought?

Follow me on BSky <- A critical mass of public policy people seem to have moved here

Consider a small donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge.