A bold pair of policy announcements eight weeks before the county council and mayoral elections which cover much of central England

Image: You and The State (1949) – Ralph Miliband (The Energy Secretary’s father) was involved in creating this document.

The Guardian has led with both:

- Wes Streeting on the huge cuts proposed for NHS England

- Sir Keir Starmer on Personal Independence Payments (of which I am in receipt of)

See also Rachel Charlton-Daley in The Lead here

“The government has already vowed to cut £3bn over the next three years and is expected to announce billions more in savings from the personal independence payment (Pip), the main disability benefit.

“The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) is preparing to publish a green paper on sickness and disability benefit reform in the next few days ahead of the chancellor’s spring statement at the end of the month“

Which makes for grim reading if, like me you are dependent on that support to pay for things like bus fares or e-bike repairs (which are inevitably more expensive than a push-bike service).

A warning from history by the former head of the Child Poverty Action Group

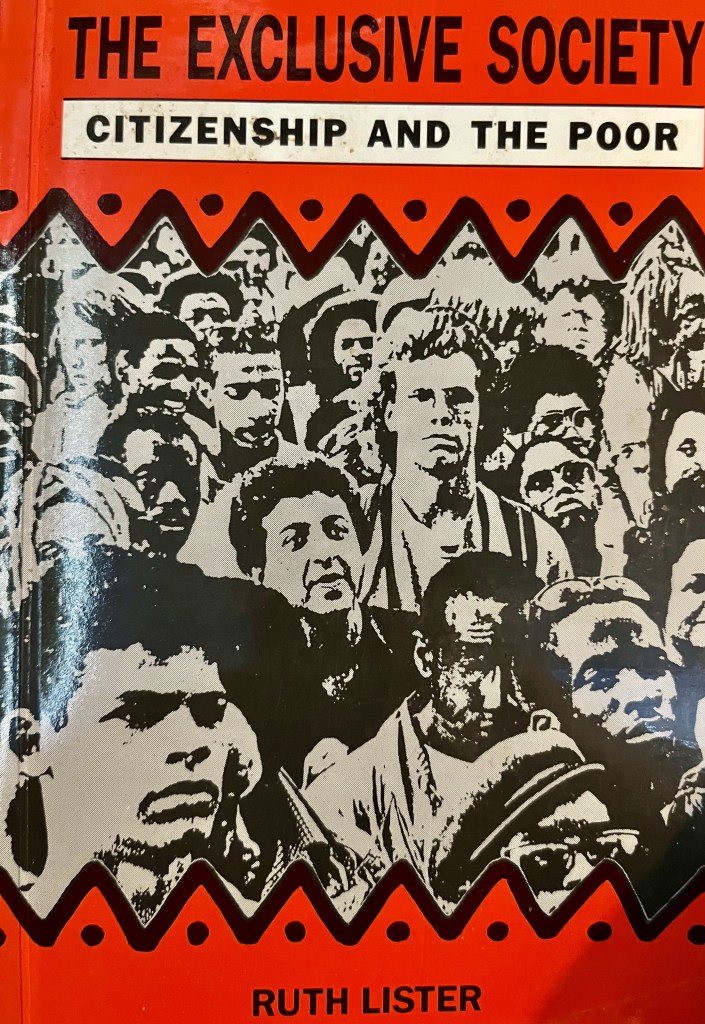

If you want to get an idea of why the policy proposals on PIP are straight out of the 1980s, see The Exclusive Society (1989) by Ruth, now Baroness Lister via the Internet Archive, or if like me you prefer a paper copy, see the second hand ones available on ABEBooks here.

Above – The Exclusive Society (1989) by Ruth Lister – browse online at the Internet Archive

I can’t recall reading a document where the moral and philosophical differences between the different policy options was laid out so clearly and succinctly. Which reflects how over the past half-century society has taken as given what were radical (right-wing) views in the early 1980s. One of the tools that those in power have is the very effective use of the media to portray those that abuse the system as somehow representative of everyone else. It’s a trope we’ve seen time-and-time again over the decades where the behaviour of the few is used as a policy tool to penalise the many. Surely we’ve become more sophisticated and smarter than that in public policy circles to come up with something better.

Which comes first, the support or the cuts?

There are two broad policy routes I can think of that ministers could go down. The traditional Tory route is to restrict funding to the Department for Work and Pensions (The Department for Social Security – once linked to the Department for Health, no longer being a thing) and leave it to the ministers in that department to figure out how to slice up the funding. The problem is that social security payments such as PIP are not something that you can allocate definitive funds to easily. By their nature they fluctuate depending on a whole host of factors as The Government states on its website here. Therefore one of the few direct policy levers that ministers have is either to reduce the level of individual payments, or make the criteria tougher – which risks some of the horrific case studies that we’ve seen in recent decades regarding ‘fitness to work’.

“With around nine in ten low-income households receiving Universal Credit unable to afford essentials, this summary draws on growing evidence to show how inadequate income can act as a barrier to work.”

Inadequate Universal Credit and barriers to work, by the JRF: 25 July 2023

The risk of such an approach is that far from getting a critical mass of people back into the workforce, ministers could end up with more people living in worse conditions and creating even more burdens on an already over-burdened NHS.

“What support could they provide in a ‘support-first’ policy?”

First of all, take the financial cuts out of the game. Otherwise the policy driver will be hitting a number with a £sign in front of it, and not about increasing the wellbeing and welfare of individuals to the extent that more of us (myself included) are in a better position to contribute towards the commonwealth and greater collective good.

The reason why I’ve used the terms commonwealth and greater collective good is because the tick-box approach to getting people into *any* job has resulted in workfare-type schemes where people have to ‘earn their benefits’ being uncooperative in the workplace because they are there under coercion and are being paid far less than the people (who might not be on much more than a minimum wage anyway) they have to work with. While it may look like a labour cost saving on paper for an employer, the impact on staff morale and the working environment cannot be the sort of workplace for the 21st Century that a Labour Government would want to promote.

Identify all of the barriers that people face, and identify which institutions or individuals are responsible for dealing with them

For example I had another Doctor’s appointment recently where I have to fill out another set of forms for an ADHD referral because the GP-shortages mean surgeries across the country are having to use locum GPs, which inevitably mean ‘continuity errors’ to put it mildly. Again, it’s a systemic issue, not one that’s specific to my case. But that means a further delay for something that already has huge waiting times anyway.

Built environment – what are the things in people’s day-to-day lives that are making their health worse, or preventing any meaningful improvement?

Furthermore, what are the resources needed – in particular with skilled labour – to improve that built environment? Are the employment strategies of the responsible institutions actively contributing towards meeting those resource needs? And if not, why not?

Enforcement of existing laws – on housing quality, on health and safety in the workplace, and on minimum wages

Take this example from Cambridge where the local community union ACORN are taking on one housing provider – doorstepping their London HQ to get a meeting where all previous attempts through normal political routes had failed. Wouldn’t it be better to have much better-resourced enforcement functions for things where the outcome benefits the most vulnerable in terms of improved standards of housing and a legal minimum wage? (Which also benefits other people around them, not just the one individual who complains?)

Delivering on the renaissance in lifelong learning and adult education that Parliament’s Education Select Committee called for back in 2020

See also two reports from the old Advisory Council for Adult and Continuing Education (before its sponsoring body was abolished by Thatcher’s Government.)

- Continuing Education report from 1983 on creating new local learning centres

- Continuing education: from policies to practice – which sadly I can only find a summary.

In Cambridge we still don’t have a purpose-built lifelong learning centre despite continued complaints from employers about the lack of skills in the labour force needed. The buck stops with ministers because the Combined Authority has told me in various responses to PQs that they have neither the funding nor the powers to do what I’ve been asking, and don’t seem to have the desire to push ministers for anything more than they are already doing at the moment within adult education and skills policy. Which I find profoundly depressing. If ministers are serious about dealing with the skills shortages, then they should be developing policies that:

- Create places where adults not only want to learn, but actually would like to simply be in day-to-day that also meets a host of other needs, including but not limited to

- Onsite healthcare (GP, dentist, non-emergency clinic)

- Creche/childcare

- Affordable and healthy canteen

- Electrified public transport (trams/light rail/suburban rail as well as buses) with frequent services extending into the evening

- Sports/leisure/active movement (which is why for a new urban centre for Cambridge that I wrote about here, having a lifelong learning college spilling out onto common land and playing fields would more than deliver on this)

- Pay people to learn – especially in those fields where there are the chronic skills shortages, prioritising groups such as the long term unemployed, those that don’t have the qualifications, and those that have a real desire to make the best of what might be a second chance in life. (Furthermore, they could be rewarded financially on successful completion of each module). I’d really like to see Cambridgeshire piloting something like this across a range of different communities and demographics.

- Encourage transport authorities to co-ordinate decent public transport provision from where there is greatest economic deprivation/greatest need, linked to training, education, and employment sites, and in the longer term look at relocating / creating new sites that are much closer geographically to where the people are, so commuting times are reduced.

“The problem is that those are long term solutions – and it seems like ministers want to move at a much faster pace”

They always do in my experience because the average lifespan of a minister in any given post is not long. (Which is one of the reasons why I think executive and legislature should be separated – get the best people in the country to run the ministries and subject them to confirmation hearings from Parliament, rather than relying on the best from a much smaller talent pool that is the House of Commons).

Isabel Hardman, writing in The Guardian notes the disquiet on Labour benches but it doesn’t look like being nearly enough to change the policy

In the same piece, she picked up on another example of why I want to see executive and legislature separated:

“The prime minister has been having meetings with small groups of his MPs where he discusses policy and strategy with them. He also has the promise of further unpaid jobs that keep idle backbenchers from plotting, with more MPs getting special “champion” roles covering different sectors and regions of the UK”

Isabel Hardman, The Guardian, 09 March 2025

If politicians want to be ministers, that’s fine. If they want to be MPs and hold the executive to account, then they shouldn’t be aiming for ministerial office. The problem is our system requires ministers to be drawn largely from the House of Commons. Every additional MP that takes on an unpaid “envoy” or “Champion” role immediately relinquishes the ability to ask difficult questions on the floor of the Commons given how tightly the Labour whips operate.

In the run up to the county council elections, Labour will need to keep an eye on the vocal party political opposition in a number of seats from The Green Party

In Cambridge, The Greens are heavily targeting Romsey Ward – a traditional Labour stronghold where they’ve not had a presence before. It would be a huge shock if they got anywhere near taking the seat. At the same time though, county councils were never Labour strongholds so in one sense if there is a set of elections where in terms of council seats they don’t do well in, this is the one they would lose the least sleep over.

On Universal Basic Income

What’s particularly striking is how the policy of Universal Basic Income stands in stark contrast to what the Government is proposing when you compare the disposition of UBI versus the cuts to welfare – not that there’s much left to cut. Furthermore, one of the pioneers of AI – something that ministers are pursuing with much vigour was quoted on BBC News saying that UBI would be needed as a policy response to the gains from AI.

“The computer scientist regarded as the “godfather of artificial intelligence” says the government will have to establish a universal basic income to deal with the impact of AI on inequality.”

Above – Professor Geoffrey Hinton to Faisal Islam, BBC News 18 May 2024

The problem is that for the Labour right wing – in particular those most aligned to Tony Blair’s ever-expanding public policy institute that now has over 900 people working across the world, the concept of a UBI goes completely against their disposition as it looks at face-value a ‘something for nothing’ deal. Which is one of the reasons why more extended in-depth pilots running for longer periods of time need to be undertaken and robustly evaluated. Because as the pro-Private School lobby found out with VAT, when some things are tried out, their bluff can be well-and truly called out.

On the NHS England proposed cuts

There has been no official announcement yet, but the mood music does not look great. Irrespective of how big the cuts to NHS England are, the instability the programme will cause in the institution will be absolutely awful. (I went through similar in the civil service twice. The first round resulted in me getting promoted up two grades and moving to London, the second terminated my career – that being the great austerity of 2010 when both my former employer and the sector it oversaw – local government, took a 40% cut to their budgets).

It’s in the nature of the beast of Macho Westminster politics to ‘big up’ themselves about taking difficult decisions. But when you’ve been through botched redundancies (that through incompetence more than anything else ended up being reversed i.e. because of Brexit then due to the woeful civil contingencies for a big pandemic) there are more than a few things that ministers could do a damn sight better on than their predecessors.

The first is basic: Remember that they are dealing with human beings, not numbers on a spreadsheet

The second relates to their party’s history: While NHS England may no longer be responsible for them, the state still is – cradle to grave services and all that. Therefore have bespoke retraining packages available to help people transition from NHS England into those parts of the local economies facing the cuts, where the skills shortages are the greatest. Also don’t use the ‘See this as an opportunity’ rhetoric unless you’re going that extra mile to ease the transition to new careers and professions.

This matters not just for NHS England but also the wider civil service given the recent headlines about performance management. How many existing staff might jump at the opportunity of moving into a different career or different line of work if given similar (or perhaps improved?) terms and conditions? Again mindful of the changing needs of economy, of society, and also the continued growing threat of the climate emergency?

The problem remains that we don’t have the local lifelong learning infrastructure to enable that retraining to take place – despite repeated calls from numerous reports and studies

But because so much of what I’ve written about in this piece are long term policies, there’s an air of inevitability that ministers will simply drive through an old-fashioned and obsolete set of policies that end up causing more harm than good.

Food for thought? (Public policy. Complicated stuff, ain’t it?)

- Follow me on BSky

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge.

Below – the Bishopsgate Institute is an example of what Cambridge could build – it’s next door to London Liverpool Street.