A superb piece by the founder of the Ninety-Three Percent Club who has put into a single blogpost what I spent over 15 years failing to do in hundreds of my own

Image: The Tackling Loneliness Hub

The title Life on a piece of paper comes from something I wrote during my final year of university.

It goes something like this:

“Born – nursery – good school – great college – top university – graduate job – marry – children – retire – die.”

I figured out this didn’t include anything about joy and happiness. Just a series of tick-boxes. Hence reading Sophie Pender’s piece with interest.

You can read Ms Pender’s piece here, and see her summary on LI here.

“When you grow up without much – without stability, without reassurance, without being told you’re enough as you are – you learn to outsource your worth to outcomes“

How many of us have outsourced our worth to outcomes set by someone else?

How many of us have sacrificed or let go something in our heart of hearts we really wanted to do in order to undertake a priority set by someone (a figure in authority) or something (middle class exams culture) else?

I expect there are more than a few of you who read this blog who ended up giving up or letting go a practical activity, hobby, or skill in order to prioritise something that was exams-related.

In my case, so many events, experiences, and incidents in my life now look very different through the lens of neurodiversity – in my case still-to-be-diagnosed AuDHD.

Dealing with the big picture and my personal picture at the same time

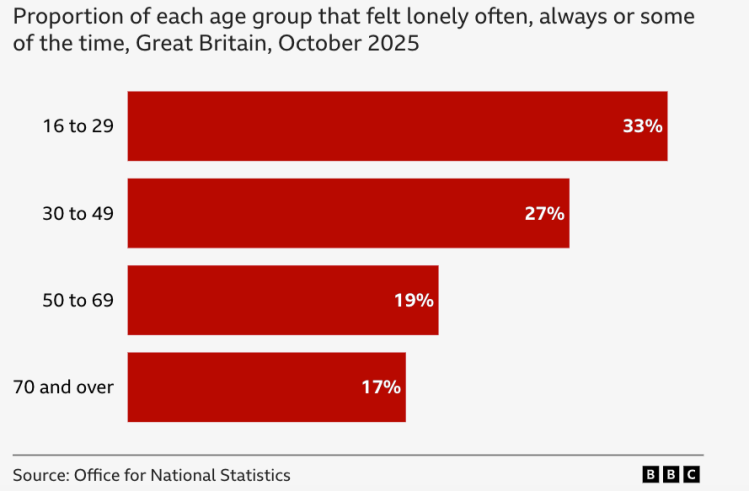

One of the subconscious reasons for posting repeatedly about loneliness in society as a public policy issue (most recently here) is that it helps me justify to myself that my own situation isn’t one of me being labelled as one of life’s losers or drop-outs – but rather something that is a far bigger phenomenon that ultimately costs the taxpayers money and therefore needs to be dealt with. (Note the mindset of quantifying financially rather than defining it in the collective social loss to society).

Above – Luke Mintz BBC News 18 Dec 2025

“We have a very linear education system, a complete mismatch as soon as one enters the real world”.

Musician Ellie Dixon, 15 Aug 2020 on Birdsite to me, quoted in this blogpost

I first saw Ellie perform at The Junction over a decade ago when she was still at school. Fast forward to today and she remains one of the most pioneering and dynamic performing artists that I have ever seen. And yet she was dropped by her record label (Decca) because they demanded that she produce more works in ridiculously short time periods that did not account for her creative needs or the creative processes involved. Again, institutions with unrealistic expectations. Furthermore, Ellie like so many women in that toxic industry has had to deal with a culture that was exposed in the politics sphere by the Commons Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee in their report Misogyny in Music.

*Don’t push too hard / someone else’s dreams are china in your hand…*

…which wasn’t quite what TPau’s 1987 chart hit sang in the chorus, but what do you do when they come true? Or as Ms Pender wrote:

“What happens when the places you’ve dreamed of going, the people you’ve dreamed of being, the ideas that have sustained you for so long, never really arrive?”

In my case no one told me that I was meant to keep on going. There wasn’t time to take stock and ‘enjoy the success’. In my case it was

- Getting into a top state sixth form college

- Getting into university (and leaving Cambridge permanently so I thought)

- Getting onto the Civil Service in-service Fast Stream (and leaving Cambridge permanently – second attempt. So I thought!!!)

All of these happened at a time before society and the medical professions knew what we now know about neurodiversity.

Above – ND Badges from Jubly-Umph because I passing by GCSEs and getting onto the Fast Stream involved expert-level hyper-focusing. I just didn’t know it at the time.

It was only many years later that I started to understand the transactional nature of UK middle class culture. If I did my part of the ‘deal’ I would be ‘rewarded’ with something. (Think of the cartoons of ‘If you clean the car we’ll buy you a pony!’ sketches). That also in hindsight meant masking heavily when it came to doing things I really didn’t enjoy. Like going to church when I’d much rather be doing something else or being with other people.

In those days there were no alternatives. Especially at primary school in the mid-1980s where school, church, and local uniformed youth group (eg Cubs and Brownies) were this rock solid trio, underpinned by common religious ceremonies such as Remembrance Sunday with The Queen (who you swore allegiance to at the uniformed youth groups) leading, and a critical mass of WWII veterans still alive who experienced untold horrors. All through the medium of four TV channels. No mobile phones, no internet. The facts were whatever was broadcast on TV & Radio or the printed word. (Not surprisingly the first university lecture I went to after leaving Cambridge in Sept 1999 overturned everything from school culture and began with: “Just because something is in print does not make it authoritative”.)

“You catastrophise that you won’t matter anymore, or that you’ll be back to the council estate.”

Above – Ms Pender again.

Catastrophising has been a permanent feature of my existence despite the various slogans such as ‘Worrying is interest paid on stuff that is unlikely to happen’ and so on. It was only as I got older – mainly after I graduated, that I learnt to cut my losses earlier. But that also came with caring less about what those around me thought about things like career choices etc. Prior to that, the people around me were people I had known for most of my life. That looks very different when. you are surrounded by fewer familiar faces with little shared history or fewer shared life experiences.

“[The drive to ‘keep going’] is incendiary and burns up everything in its path until you’ve deprived yourself of all things that aren’t related to professional success: your relationships, your health, or – dare I say – fun.”

Ms Pender writes – and this was where I got to towards the end of the Labour Government. It got to a point where spending 3 hours a day commuting from Cambridge crushed my physical health, and left me spending most Saturdays and Sundays in bed asleep. What I didn’t realise was that by the end of each week I was suffering from ADHD/Autistic burnout. I had no life outside of commuting and it was at that point I realised I could not keep that going for another 25 years. Hence when the Coalition started slashing and burning, I took redundancy.

“This idea of a destination that you reach where confetti cannons go off – and you’re given the key to the city – and there’s a cake baked out of rainbows and smiles – was never real to begin with.”

Ms Pender again – she’s right.

Although in my case my health crashed and burned, a breakdown leaving me with permanent CFS/ME in 2012. The problem was it took over a decade to get it diagnosed. Had I been properly referred and assessed early on, I would have got far more support from the state rather than ending up where I have done having to boomerang back into my childhood home. I’ve still got another two years to wait for an ADHD/Autism assessment on the NHS – noting that ‘Right to Choose’ means that you need to pay for private prescriptions despite an NHS-funded assessment from a third party. Most GPs don’t do ‘shared care’ arrangements – something the Government (past and present) have made a complete hash of. As a result, and as I wrote in August 2020, there’s so much of my old active life I miss that I’ll never get back. And that’s still really hard to take.

“You don’t heal the ache of “never enough” by finally being enough on paper.”

Furthermore, it cannot make up for the lack of community and the lack of multiple shared experiences over an extended period of time – something I wrote about missing out on at the end of this blogpost from 2023. It’s one of the reasons why I want the expanding Cambridge to build a new large lifelong learning centre capable of hosting a wide range of activities including sports, leisure, and hobbies. Multiple shared experiences in a shared space where you can find those with multiple shared interests. I hoped I would find those communities at college, at university, and even in the civil service. But I never found my tribe. Furthermore, I acknowledge that I never will either. The amount of shared time and shared activities needed to create, strengthen, and solidify friendships – something we perhaps take for granted in our school days, is something that’s beyond my total of waking hours. And that’s before I’ve got out of the front door.

The final two-three paragraphs from Ms Pender are the hardest for me to process from a personal perspective

“Let the first bit of kindness you give yourself be this realisation: that you can allow yourself to be seen, loved and appreciated for where you are, not just where you’re going.”

I wouldn’t know where to start – but that’s more to do with my personal circumstances. Since I finished my A-levels not one person from childhood, from my university days, from my civil service days has ‘stuck with me’. That’s not to blame anyone/everyone else. Had I known half the things I now know about all things neurodiversity, equalities, politics, and democracy back in my formative years, I’d have taken a multitude of different life decisions compared to the ones I actually took. Hence my observation in a recent blogpost that much as I’ve wanted to live a life with multiple connecting threads starting at early childhood and extending into old age, I’ve ended up living a life that has been a series of discrete episodes – often where I feel like I’m on the outside observing rather than an integral active participant. One where the people I was at university with don’t know the people who I worked in the civil service with who today perhaps don’t know the people in local history circles that I’m acquainted with.

One thing Ms Pender’s piece has taught lots of us going by the responses

As she concludes, it may feel like these feelings of loneliness and isolation are unique and personal. But as so many people have testified in writing in response, there are far more of us feeling similar. One of the few big positives that emerged from the early days of social media was the ability of people with shared experiences have been able to gather together in campaigns on and offline to change the way health services deal with neurodiversity. That’s not to say there isn’t more that needs doing. There clearly is. Just don’t get me started on how we’ve ended up in a world where social media all too often seems to be used for anti-social purposes. That’s for another time and post perhaps.

If you are interested in the longer term future of Cambridge, and on what happens at the local democracy meetings where decisions are made, feel free to:

- Follow me on BSky

- Spot me on LinkedIn

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge