Compared to the 9,000 or so who took GCSE Maths that year, that’s under 2% of the cohort.

In London the percentage (using a much greater baseline of nearly 90,000 year 11 students using the figure for GCSE Maths as a very rough approximation for the total number of candidates taking GCSEs per county) was around 5%.

You can play with the data across a range of subjects from OfQual here.

I’m generally of the view that GCSEs – and our exams structures in general are hopelessly obsolete for the 21st Century, and that our teenagers deserve something much, much better. In the meantime, could we encourage the greater take up of the subject? Furthermore:

- could local/county level public and voluntary institutions support their learning by getting students out of the classroom?

- Would a greater uptake result in positive civic benefits (more candidates for election, a higher turnout at elections, local issues followed up faster, more candidates applying for local council jobs that remain unfilled) over a longer period of time?

I’m not reading too much into the attainment scores because unlike say Further Maths at A-level, it’s not designed to stretch the the highest academic achievers.

Also, it’s still too early and the cohorts too small to start pulling out some longer term trends. Furthermore, when you think about the subject area, it *has to be accessible* to as many as possible – including those who will struggle to reach even the lowest GCSE grades. Hence pondering alternative approaches last week. Hence I’ve given my copy of Jenny Wales’s book to a local community activist who I knew from school back in the 1990s but who didn’t go to university to see what her (vastly larger than mine) social and community network (i.e. friends!) think about the contents, what they would strike out, and what they think is missing but needs covering, and whether it is accessible enough.

I’ll try and avoid the annual round of “Are [school exams] too easy?” noise from the print and broadcast media that has been around for decades. The world that my generation was [badly] prepared for in the mid-1990s after a decade-and-a-half of Tory austerity is a very different one to the one that today’s teenagers are facing. Also, recall this from 2005:

“Are exams really getting easier? Maths graduate Tom Whipple gave himself just two weeks to prepare for an AS-level exam in that most maligned of subjects … sociology”

Tom Whipple, The Guardian, 16 Aug 2005

I recall at the time I said that this was not comparing like-with-like as he wasn’t studying other A-levels at the same time with the same amount of pressure to make it count. Turns out he was called out on it by more than a few people – which he covered in a follow-up article.

“Your experiment kind of ties in with the sensationalist way of dealing with these subjects. What you would need to have done is to take another AS-level in the same time period to make a comparison. You are now 23. You have been through a lot of education. You have maturity, so I suspect you would probably pick up other AS-level subjects quickly as well.”

Dr Patrick Baert, senior lecturer in sociology at Cambridge University, to Tom Whipple, in The Guardian, 23 Aug 2005

It’s worth reading Mr Whipple’s second article all the way to the end – for his conclusion may surprise some of you. This is also where it links into the teaching of citizenship studies. Because at GCSE and A-level standard getting the balance right between breadth and depth of content isn’t easy. Is this where modular systems of learning are more useful – where teachers and colleges can select the modules within a subject area that are most relevant to the students, communities and places where they live?

“Should Citizenship Studies be a thing that gets examined?”

That comes back to Michael Rosen’s point regarding first principles: i.e. “Why exams?” What specific social and economic issues are exams and the examination system designed to solve?

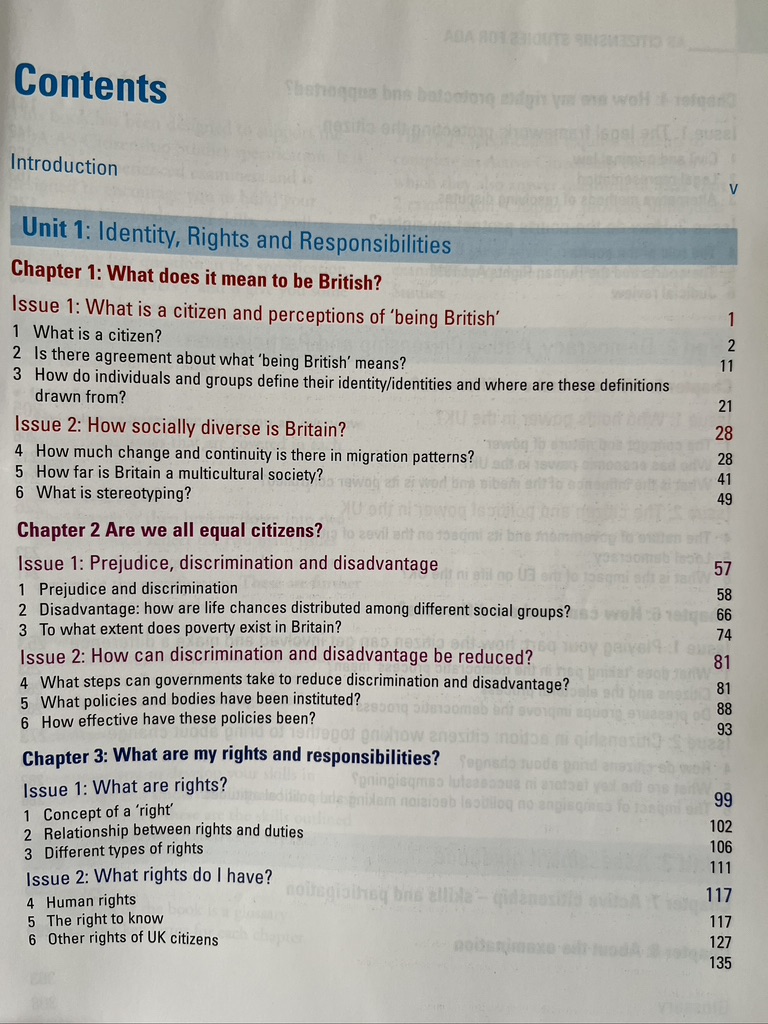

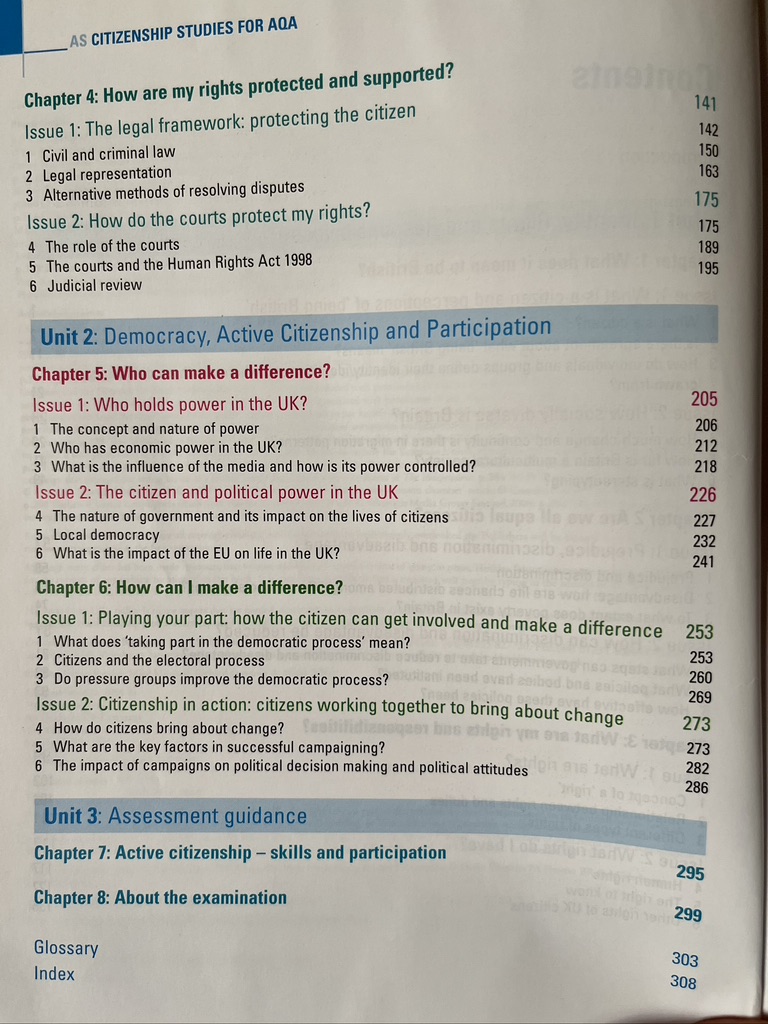

As I mentioned in a recent blogpost, town planning, and healthcare are barely covered in the GCSE. Yet taking this diagram from the AS Citizenship 2009 workbook, and cross-referencing it with the sort of things the public regularly raise as issues locally, how do the exam boards ensure that the GCSE is not just some academic exercise, but equips students with knowledge on how to engage with the institutions of the state?

AS Citizenship Studies for AQA (2009) by Mitchell & Co, p231.

Things that refreshed courses could include:

- Standing up for your legal rights (specifically knowing when & how to complain (for yourself and on behalf of others))

- Who decides what gets built, where, and how?

- Who decides what healthcare services are provided in my area, how and why?

Unlike some other GCSEs, learning through citizenship studies should open doors to a range of choices for further study *and* equip students for the real challenges they may face in the outside [of school/college] world. Which is often why I describe my secondary school experiences as ‘being educated to be ignorant.’ I still recall one of my fellow economics’ students giving his repeated refrain: “If it’s not on the syllabus and we’re not being examined on it, I’m not studying it.” It was something several of us struggled to respond to, because like him we had all been conditioned to accept not only that your exam results were what mattered the most, but that getting the maximum grade on the minimum possible effort was the way to do it.

Furthermore, some subjects were ‘more equal than others’ – losing count of the number of times random members of staff in both further and higher education bemoaned the existence of sociology/media studies vs physics and chemistry.

Which is like comparing chalk and cheese. Both are important to society – just in different ways. In the world we live in today a strong case for compulsory media studies GCSE could be made given the current systems. (Examination, and political!)

What none of them complained about was the system we were in that did not allow my generation in the mid-late 1990s to learn more about both.

Collective learning on citizenship and communities

As I mentioned at the end of this blogpost, Cambridge’s offer on collective learning on citizenship and communities – as well as democracy and politics is very limited outside of formal, full-time courses.

Above – the U3A-Cambridge 2023-24 Programme which includes three separate options per week on current affairs – for those of you who would like to talk politics.

“Why not read a book or something?”

Because politics is the means by which people decide how resources should be allocated in societies with unlimited wants. At some stage we have to move from books to debates. (I dare say that at a community level, we have too few of either!). Our local public institutions don’t create the spaces to enable wider debate around the evidence bases that inform their policies. Look at the the history of GCP and their busways proposals. Recently the LRTA published their book with the local transport ministers titled The Trams Return.

Also brand new books are not cheap, and neither is access to academic journals when you’re outside an institution. This something I was reminded of when at the RSPCA Bookshop on Mill Road I picked up Community: welfare, crime and society <– (Going cheap online) from 2009 published by the Open University (28,000 used books on ABE too). Although brand new academic books very quickly lose their financial value and after a couple of years can often be picked up for less than 10% of the price they were sold for brand new – especially if/when it has been superseded by a newer edition. The only caviate with that is remembering to ask yourself: “What have we learnt since then?”

One classic example is the now defunct AS in Citizenship Studies from 2009

Above – from AS Citizenship Studies for AQA (2009) by Mitchell & Co.

Inevitably it pre-dates the EU referendum so the things applicable then won’t necessarily be applicable now. And following the next general election, things will have to change again whoever gets in because the whole policy framework around UK-EU relations is so unstable. The very opposite of what governments (and commerce too) ideally want in international relations. (Those of you who are hardcore could compare the old AS Citizenship from 2004 with the state of society today!)

Another useful-looking book (which I’ve just bought for under a fiver) is also from the mid-2000s: Managing civic and community engagement (Open University – 2007) – only it asks the question of what the relationship between higher education institutions and their host towns/cities should be like. Cambridge has 800 years worth of history explaining what it ***should not be like*** so I guess that’s a start. Also, one of their three case studies is Brighton – where I used to live. Again, this matters because of the housing crisis that is also affecting students where universities have expanded far too quickly without ensuring the support infrastructure is in place.

I found out the hard way nearly a quarter of a century ago in Brighton about how unfair it is on both students *and* local residents on low incomes get thrown to the wolves of the local housing market. In such circumstances it’s a landlords’ market – and inevitably one where those with the least risk exploitation. Sadly there has not been the political will to deal with both symptoms and root causes – which are inevitably complex as it involves housing, town planning, transport planning, local government, and higher education.

One of the things that the town-gown Cambridge Land Justice Campaign is already looking at is the role of the University of Cambridge regarding its wider civic and social responsibilities towards the people of Cambridge – in particular those on the lowest incomes in parts of our city hit by multiple deprivation.

If you are interested in the longer term future of Cambridge, and on what happens at the local democracy meetings where decisions are made, feel free to:

- Follow me on Twitter

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge.