The group We’re Right Here is making the case for a new Community Power Act

The problem is that the proposals need a host of other radical policies – ones that ministers are showing little genuine interest in – for the proposed legislation to achieve its aims. These radical policies include but are not limited to:

- A four day week

- Doughnut economics and [insert desired time frame]-cities.

- Universal Basic Income / Citizens’ Income

- Internalising externalities – making the producer pay for the damage their activities have on the environment and society

- Transitioning away from an extractive, rentier economy

- Overhauling the land and property ownership systems

- Tax justice

- Empowering local government to raise revenues from a much wider range of local taxes without Whitehall/Treasury intervention

- A massive expansion in lifelong learning

- A massive expansion in public transport and active travel networks

“That’s a big ask!”

It is – and the difference between the tinkering with the system that we see all too often is that proposals that come from the centre keep the institutions of power barely touched. Hence why I think the main proposals for the Community Power Act need to deal with some really difficult issues beyond their proposals (and team up with other campaigns) in order to have a chance of success.

The Community Power Acts’ top three calls

- Communities should have a legal right to self-determination

- Communities and councils would come together to form Community Covenants

- An independent Community Power Commissioner would be created

The big problem is with 2). Communities and councils have neither the time nor the resources to create community covenants.

Within 1) there are three more things.

Above – CPA proposals (2022), p5

With any new rights for individuals or groups, one question to ask is how much capacity do they have to make full use of the rights you want Parliament to grant them in law?

In Cambridge, a ‘community right to buy’ would sound laughable to many local residents because house prices and land price speculation is so high. Furthermore with so much land owned by long term institutional landowners such as colleges, what hope is there to purchase the land or longterm leaseholds to build what ‘the community’ wants? (Hence the formation by students of the Cambridge Land Justice Campaign) Furthermore, what is ‘the community’ in an era of high population turnover driven by employer-driven systems of shorter, fixed term contracts rather than long term open-ended contracts?

20 years ago working at a supermarket while doing my post-graduate diploma in history, I and many other members of staff were on temporary contract after temporary contract. It was incredibly destabilising for the staff that were in reality permanent staff, because none of them knew whether their contracts were going to be renewed at the end of it. (And all of the health and social costs that come with working under such a shadow). For an employer it’s an easy wheeze to get around workers rights because rather than going through convoluted disciplinary processes, you simply do not renew the contract at the end of the period and the individual ceases to be your concern or responsibility. Fast forward to today and the structure of ‘the gig economy’ combined with ‘workfare’ schemes to get people into work – any sort of work irrespective of skills-matches. Under that sort of mental pressure of not knowing where your future income is going to come from, it’s no wonder that people choose not to engage in local community activities.

What incentive is there for anyone to engage positively with state institutions when their experience of state institutions is a negative, oppressive one?

I was struck by the testimony of the old Risinghill school in Islington

The account by Leila Berg in 1968 you can browse here – TW: corporal punishment/violence. It’s the testimony of the children from their previous schools that was sobering. The culture of casual violence towards the children is a soul-destroying read. This was at the time when there was much greater pressure to ban corporal punishment in schools – something that was only finally outlawed in 1986. The Risinghill School had a pioneering headteacher who tried to remove corporal punishment as a means of discipline, but ended up coming up against an establishment of old-skool disciplinarians not just within his own profession but also from the local borough council. Inevitably it hit the headlines of the day. You can see why for some generations there is still a reticence of going back to any place that resembles ‘school’.

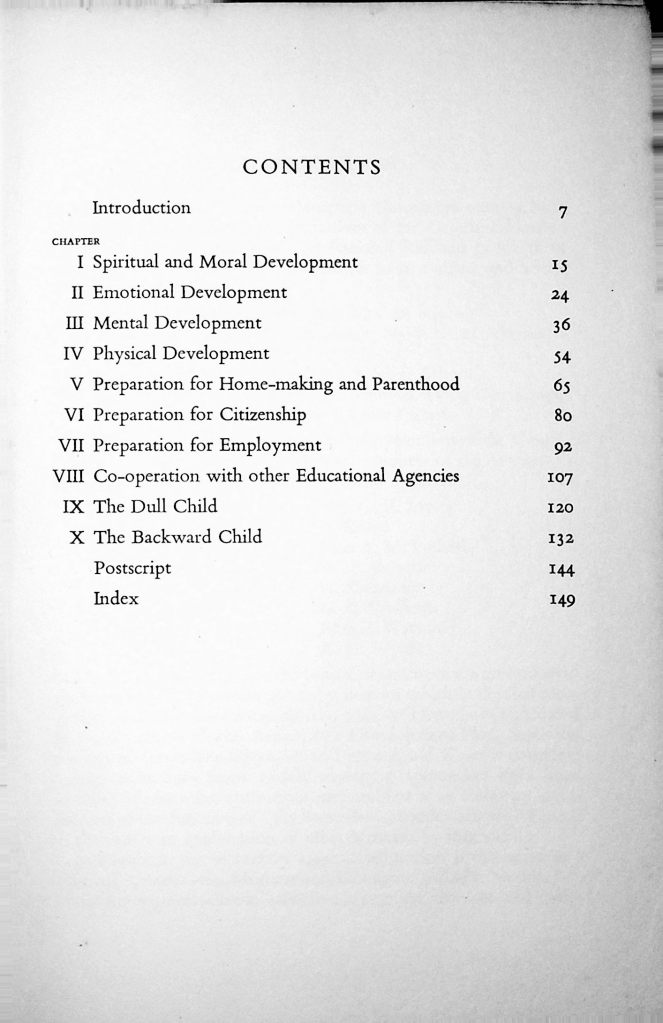

Inevitably it took time for the pioneers to win through – but even then the lessons of the post-war years are still to be implemented regarding citizenship education for children & students – and the role that wider society has to play. The interesting guide from Cheshire’s Education Committee completed in 1957 and published in 1958 (which I’ve digitised here) on secondary moderns – so for children who didn’t get into grammar schools, has a fascinating trio of chapters that look at educating teenagers for the world outside.

Above – from The Cheshire Education Committee

- Preparation for home-making and parenthood

- Preparation for citizenship

- Preparation for employment

Fast-forward to the mid-1990s and after a decade and a half of Conservative education policies I can only describe their offerings as woeful on those three fronts. The crushing of secular youth services outside of school hours resulted in the same situation we are seeing today with ministerial rhetoric on being tough on crime even though their jails are packed – have a browse through the British Newspaper Archive online (it’s free to access in public libraries) and see what your nearest local newspaper was saying in the 1980s and 1990s. (This is why social history matters!)

Hence also why I’m making a big deal locally about citizenship education in and around Cambridge. That only 145 students in Cambridgeshire elected to take Citizenship Studies GCSE mainly because so few schools offered it, speaks volumes.

“How do we get more schools to offer GCSE Citizenship Studies – given it’s a useful non-academic alternative to traditional humanities such as history, and geography?”

For me the bonus of GCSE Citizenship Studies is that it can be tailored for multiple abilities in a way that is harder for academic subjects. The practical activities embedded in Citizenship Studies can, if planned well, reflect what students will be faced with shortly after leaving school. In particular those that don’t go onto university. It is those community/society-facing activities that for me are just as, if not more important than the final grade. This matters if your cohort is not one full of students aiming for the highest GCSE grades and a world where a dropped grade can make-or-break an application.

This is also why I think that GCSE Citizenship Studies would be a useful course to offer alongside basic skills courses in lifelong learning centres and county/region-wide further education institutions. It puts the skills that participants are learning directly into an applied setting.

“That’s the smaller picture at a community level, but what about the big picture?”

If we are to get the best from community power, then the people that make up those communities need the support in order to do so. That means getting some structural essentials right:

- Shorter/quicker commutes to work

- Flexibility with home-working where possible

- Removing the worry about income streams

- Creating more time for more people to participate

…amongst other things.

Hence the importance of radically-overhauled towns and cities in favour of public transport (electrified) and active travel, to more localised community working hubs and fewer mega-offices that need huge numbers of commuters to occupy them during the day. It also means moving away from the extractive economy – hence the publicity around independent shops and farmers’ markets where locally-generated wealth can be kept circulating within local markets rather than being extracted and exported elsewhere. (Don’t get me started on UK Crown Dependencies and tax havens! Read Richard Murphy’s book on them instead!)

There is more to community power than what I’ve covered so far. See also this piece about pride of place, and also this on a community-powered NHS. I can’t pretend the problems will be solved overnight. They won’t. It’s going to be a long slog. It’ll be interesting to see what the political parties offer at the general election on community power. Will they have learnt the lessons from previous governments’ policies or will we go around in circles again?

If you are interested in the longer term future of Cambridge, and on what happens at the local democracy meetings where decisions are made, feel free to:

- Follow me on Twitter

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge.