The Regional Water Resources Plan for the East of England has revealed how under-prepared our part of the country is for the climate emergency – whether for droughts or extremely heavy rainfall.

TL/DR? Read Mark Williamson’s thread here. See also BBC Cambridgeshire here. Also, go and see the Pure Clean Water film about Cambridge’s water crisis too.

Many moons ago during my civil service days, I spent about a year working on sustainable new homes policy – one that combined town planning, housing, and climate change policy. This was back in late 2007 to late 2008. It was one that I struggled in and one that would lead me to burning out completely – something from which I’ve never recovered from. Despite that, it’s only been in recent times that I realised I was absorbing lots and lots of information very quickly – information that my anxiety-riddled mind seems to be able to recall. Hence this post will feature seemingly random hyperlinks that feel like they are pulled out of nowhere. But let’s start with the important stuff.

The Report – if nothing else, browse through the summary

The report’s landing page is here. Scroll down until you see the scene below.

Above: Bottom-left, the Non Technical Summary. Bottom-Right, the main report

“Hang on, who are Water Resources East (WRE) again?”

You can read their about us page here. They are one of five groups tasked by Central Government for coming up with long term plans for water resource management. You can read about their governance structure as an independently constituted organisation here. Finally, you can browse through their member organisations here – noting that the University of Cambridge appears to be conspicuous by their absence.

Musician and environmentalist Feargal Sharkey picked up on the report’s publication – and he is scathing.

Re Mr Sharkey’s point about the river charities being involved, they have little choice. Ministers have effectively compelled them to be involved by the direction in the Environment Agency’s policy paper of March 2020 provides.

Must, should, could

From the summary document (second from the top here) on p11 you can see what ministers expect to see in the documents. If they are not in there, the draft plans are rejected and have to be remedied. On the ‘should’ while these criteria don’t designate an automatic rejection, you’d have to have a very good reason for not having, for example engaged widely with river charities. Furthermore, if those things are not in the documents, Parliament starts asking questions of those involved as to why this is. In the case of river charities, that may also mean having to answer questions from Parliament. Far less hassle to be involved from the start.

The problem is – as Mr Sharkey rightly points out – is that the good names of the river charities risk being ‘greenwashed’ (or blue-washed) as cover for a flawed plan

The Environment Agency’s failings as a watchdog.

The Environment Agency was established by Section 1 of the Environment Act 1995. That Act of Parliament imposed on the Environment Agency a series of legal duties including:

“generally to promote—

- (a) the conservation and enhancement of the natural beauty and amenity of inland and coastal waters and of land associated with such waters;

- (b) the conservation of flora and fauna which are dependent on an aquatic environment; and

- (c) the use of such waters and land for recreational purposes;”

There are other duties imposed by law on the Environment Agency – not just from this Act but from pieces of legislation as well. It was the failures to meet some of those duties (as explained by Gordon McCreath of Pinsent & Masons here) that resulted in campaigners taking legal action against Ministers responsible for the Environment Agency, the High Court ruling against the Government.

You can read the full judgement here. What’s *really striking* is the final paragraph at the end of the judgement: The Secretary of State for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (at DEFRA) did not provide all of the information required for the public to examine as required by the regulations concerned – in this case the application of an EU directive into UK law – and an EU directive that UK civil servants would have worked in partnership with their EU counterparts before being signed off by amongst other bodies, the Council of EU ministers from national governments. I.e. a UK Government Minister with policy competency for the environment would have been involved in the process of creating the directive. i.e. it is not something randomly imposed on the country. A shame no one explained this clearly and repeatedly before the EU Referendum!

So. The Plan. For East Anglia

Some of you may recall the questions about the water for 14,000 new homes, followed by the reservoirs plan which was then subsequently confirmed as Chatteris. None of those are nearly enough for what’s coming. Put it this way, we are in uncharted territory. The WRE Plan says so.

“Multi-sector, long-term water resources planning at this scale has not been done before in this country. Much progress has been made but also gaps identified that will need to be addressed in time for the next round of regional plans.”

WRE (2023) p3

“Ohhhhh F***!!!”

And that is precisely what is needed as rainfall becomes increasingly unpredictable, just as we were warned ages ago.

“Subject to final requirements due to be set in a second National Framework for Water Resources expected in spring 2025, the next iteration of our regional plan will be finalised in 2028.”

Dr Paul Leinster. WRE (2023) p4

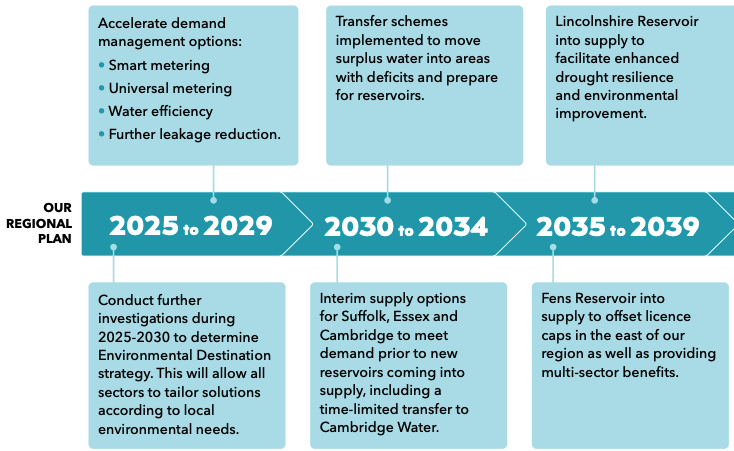

That next iteration better be more comprehensive – much more – than this one. The executive summary reveals the huge gap in demand management options.

Above – WRE (2023) p5

What is missing: Retrofitting – the detail

As Monica Hone of the Friends of the Cam told BBC Cambridgeshire, this is too little, too late.

“Water companies have repeatedly failed to plan for the future”

Monica Hone to BBC Cambridgeshire, 13 Dec 2023

We should be a long way into retrofitting our built environment by now. Furthermore, if ministers in 2015 had not scrapped the Code for Sustainable Homes (that I worked on during my civil service days mentioned earlier) then the new homes built since 2016 would already meet the high water efficiency standards that they are now talking about! But they got lobbied by some big developers and the rest is history.

“What’s the Code for Sustainable Homes?”

It was a policy brought forward by the last Labour Government to try to improve the standards, sustainability, and environmental performance of newbuild homes. (Not existing ones).

“It was launched in December 2006 with the publication of Code for Sustainable Homes: A step-change in sustainable home building practice (Communities and Local Government, 2006) and became operational in April 2007.”

Code for Sustainable Homes – DCLG/Gov.UK (2010) Preface p7

The whole idea was to provide a means for the building industry to prepare for a point in the future when homes would need to be zero carbon, use minimal amounts of clean water, and have an extremely low environmental impact. Therefore ministers approved the creation of this national standard that could be brought in by both the local development planning system *and* the building regulations.

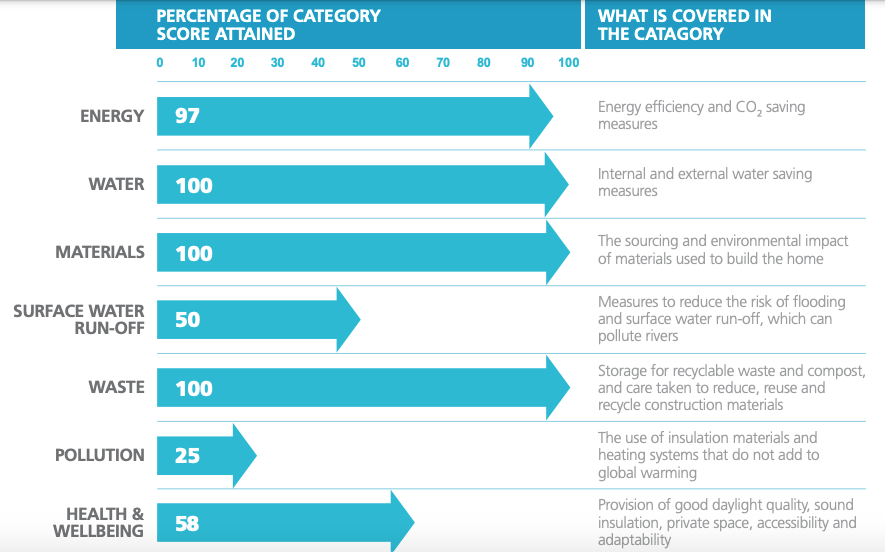

The standards in the Code for Sustainable homes covered:

- Energy and CO2 Emissions

- Water efficiency

- Materials

- Surface Water Run-off [because flood prevention]

- Waste

- Pollution

- Heath and Well-being [this included a standard to promote the construction of homes that are accessible and easily adaptable to as home owners got older] and to meet the changing needs of current and future occupants.

- Management

- Ecology.

The above is also from p7 Preface

The Code had six levels – one to six. Builders had to meet the minimum standard for each of those categories for each levels to be awarded the certificate which then estate agents could use in marketing. Think about the present fuel crisis and high energy bills?

When you look at the cases studies for the new homes of the late 2000s published by the Government (DCLG) in 2009 here, you get to see what the homes looked like and a sense of how they were designed and built to be more sustainable than the newbuild homes of the previous generation.

Above – Code for Sustainable Homes – Case Studies. DCLG / Gov.UK (2009)

Having that system enable local councils to impose a single sustainability standard across their areas. Furthermore, they were able to negotiate higher-than-minimum standards in specific developments.

“Existing planning policies already require higher standards in some areas. The North West Cambridge Area Action Plan requires Code for Sustainable Homes Level 4 for any dwellings approved on or before 31 March 2013 (up to a maximum of 50 dwellings) and Level 5 for any dwellings approved on or after 1 April 2013”

South Cambridgeshire District Council – Issues & Options Report (2012) p85

What does this mean in practice? The technical guidance tells us

Code Level 4 dwellings have to meet a maximum average use of 105 litres per person per day, and Code Level 5 reduces that to 80 litres per person per day.

Above – Code for Sustainable Homes Tech Guidance 2010, Water, p82.

How this works out inside a house for a Code level 6 home could, according to Zero Carbon House Birmingham, include:

- “6/4 Dual Flush WC;

- Flow Reducing/Aerating taps throughout;

- 6-9 litres per minute shower (note that an average electric shower is about 6/7 litres per minute);

- a smaller, shaped bath – still long enough to lie down in, but less water required to fill it to a level consistent with personal comfort;

- 18ltr maximum volume dishwasher;

- 60ltr maximum volume washing machine.”

It also goes on to state:

“To achieve the standard would also mean that about 30% of the water requirement of the home was provided from non-potable sources such as rainwater harvesting systems or grey water recycling systems“

Zero Carbon Homes Birmingham

Which is a challenge-and-a-half if you’re trying to retrofit somewhere! The problem is that since the scrapping of the Code, ministers chose not to tighten the Building Regulations covering water use.

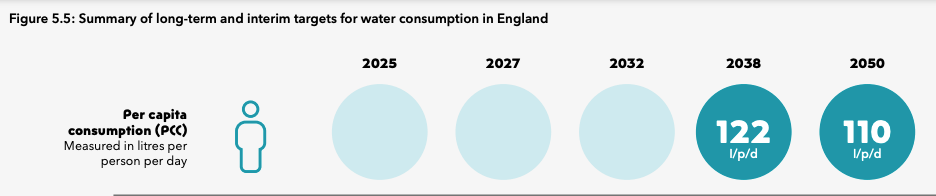

“In England, the regulations require that the average water usage be no more than 125 litres per person per day unless the planning permission for the home has specified that this needs to be reduced to 110 litres per person per day.”

LABC News 2021

That means since 2016, new homes that have received planning permission have been able to install less water efficient fittings as a result of ministers scrapping the Code and refusing to tighten the water efficiency regulations in the Building Regulations. Furthermore, national planning policy (again, signed off by ministers) prevents local councils such as Cambridge City Council and South Cambridgeshire District Council from bringing in higher sustainability standards if they are already accounted for in the Building Regulations. Developers lobbied heavily against this in the public hearings, insisting that councils could not go beyond what ministers had prescribed in the Building Regulations. Hence Cambridge’s current local plan (2018) here is stuck on the commitment of 110l/p/d rather than 80 or 90.

The problem is we like our luxuries

As my line manager at the time told me, once someone has bought their home there is nothing to stop them from ripping out the sustainable water fittings and installing big baths and power showers. How do you account for that? What should the public policy response be?

“How do you go about retrofitting entire cities?”

The non-technical summary doesn’t even mention the term retrofit. The target ministers have set to get the whole country down to the levels currently required for new build homes is a long way into the future.

Above: WRE (2023) p51

“Why the gaps?”

That presumably is how long they think the retrofitting will take before we get to the present standards in the Building Regulations for Water Efficiency.

“But we don’t have the time to wait!”

Exactly. That’s why I think decision-makers are in denial about the scale of the problem. Because to retrofit an entire city requires the commitment of huge sums of funding, the mass mobilisation of resources, and a national retraining scheme the likes of which we’ve not seen since war time.

Retraining the workforce – which will require a huge social cultural change

i.e. Middle class types getting their hands dirty – as one of my old friends from school told me several years ago. His parents were in solid graduate level jobs in the 1980s/90s and many expected him to become one of the bright ones to go onto university and middle-class-is-magical life. Then for a host of reasons he, like too many others I grew up with, were failed by schools, local public services, and ministerial policies of the era and had to overcome huge adversity before finding their feet. In his case he took up a trade, became very successful at it, and seemed to end up much happier than many who ended up going down the university route which turned out not to be the ‘land of milk and honey’ that 1990s South Cambridge made it out to be.

Hence why when ministers started talking about apprenticeships much more positively in the late 2000s, my reaction was: “Get back to me when Etonians start rejecting places at oxbridge for apprenticeships.” Yet here we are with:

- an economy that has a massive skills mismatch,

- where curriculums and opportunities to study both a trade and an academic subject at the same place seem incompatible

- where education is framed through the mindset of exams and employment only (i.e. not for the love of learning and knowledge)

- where you have one shot at one subject or career which if going to university you have to take out massive loans even though successive governments have created an economy & society where there are no longer ‘jobs for life’ for the many, but regular career changes

- where ministers demonise people who come from abroad to fill the skills gaps while failing to maintain pay, terms, and conditions of those occupations our society is so dependent on that such workers (eg medical professionals) are leaving for other countries such as Australia.

“You can hardly expect a regional water partnership to sort out those issues!”

No, but we can expect them to be much more clear about the challenge that we face. And it’s not like they haven’t had time to seek advice on the workforce requirements to quantify some of those challenges. Even if the advice has been ‘Too big to calculate!’

If the worst comes to the very worst – and running out of drinking water isn’t something anyone should have to experience, ministers do have emergency powers. Not quite at the level that Clement Attlee tabled in Parliament in the dark days of May 1940. For example the Civil Contingencies Act 2004 explicitly rules out conscription for military service. (S23(3(a))) CCA 2004. Whether S22(3(k)) could be used to create new regulations enabling ministers or other designated persons to direct people into civil jobs/functions they might otherwise not want to do…is an interesting discussion point. For example if a person is qualified to undertake a role but is currently working in a different job, could the law be used to ‘call up’ such persons, give them a quick refresher before deploying them? Civil contingencies policy means having to discuss and work through some frightening scenarios, and as the CV19 Inquiry is rightly asking, were those ongoing discussions and preparations actually happening in the years prior to the first lockdown?

“We’re not going to see vast sections of the population being conscripted to become plumbers are we?”

No – that would completely misunderstand the challenge. The challenge is an organisational one more than anything else – and a very, very complex one at that. Yet coming back to May 1940 as France was about to fall, the new Deputy Prime Minister tabled what today would be considered (even by CV19 times) an extraordinary piece of legislation.

“I believe that at this critical time the vast majority of the people of this country will willingly give their services to the country, and will do all that is asked of them. We introduce this Bill not because we have any doubt of the willingness of the people, but because in a difficult emergency like this there must be the necessary power in the Government.”

Clement Attlee, House of Commons – Emergency Powers (Defence Bill) Second Reading. 22 May 1940 vol 361 cc154-85

Same point applies – the Pandemic has shown to us all how many of us were prepared to do our part and more. Mr Attlee – who had spent part of the First World War in the trenches, rising to the rank of Major, would have been more than aware of what he was asking of people. The opening paragraphs of that speech must have been – and still be some of the most serious words any Minister of the Crown has had to read out to Parliament.

“The Minister of Labour will be given power to direct any person to perform any services required of him [for the purposes of the defence of the Realm and the efficient prosecution of the war].”

Clement Attlee, House of Commons – Emergency Powers (Defence Bill) Second Reading. 22 May 1940 vol 361 cc156

At the time, Prime Minister Winston Churchill was not a popular figure in the Labour Movement – not least because as Chancellor of the Exchequer in Stanley Baldwin’s Conservative Government, he helped put down the General Strike of 1926. On the trade union side was a rising star in the mighty Transport and General Workers’ Union, Ernest Bevin. Even if Parliament granted any minister the power to conscript the workforce of the country, Churchill knew he did not have the consent, legitimacy or trust to make use of that power – even in a life-or-death struggle against an invader. There was only one figure at the time in May 1940 that the workers in industrial UK might agree to work under, and that was Mr Bevin – or Labour’s Churchill as Andrew Adonis dubbed him. There is no modern-day equivalent. PM Boris Johnson appointing Jeremy Corbyn – or John McDonnell who at least did a Masters in Economics, as Chancellor at the CV19 outbreak doesn’t even come close. Hence in May 1940, at newsreel cinemas around the country, this speech by Mr Bevin was broadcast.

Above – Ernest Bevin, May 1940, British Pathe

Browsing through the Committee Stages of the Emergency Powers (Defence) Bill that followed straight after (have a browse here), it’s clear that Mr Attlee was much more concerned about organisation and ensuring that both employers and trade unions worked together for the common good – in particular to increase production.

“What’s all of that got to do with the water crisis and climate emergency?”

The words ‘crisis’ and ’emergency’ provide part of the answer. How do ministers propose going about filling the skills gaps in those fields where there have been chronic shortages of skilled workers – in particular those locally trained? Those long term shortages are a symptom of a major public policy failure over successive governments. What is the plan to reverse this? (One of the reasons why I’ve been going on about lifelong learning and adult education for so many years).

How do we ensure we’re producing the right amount of components and materials needed for retrofitting? Mindful again of the transport emissions that come from importing goods from abroad. How do things look when you are compelled to include the environmental costs in the transportation of imported goods and components? What does that mean for existing local economies? Will ministers and local councils need to prepare for a potential renaissance in local, smaller-scale skilled manufacturing?

What policies are there to incentivise people to switch careers? (eg paying for tuition costs and providing grants for costs of living like in the olden days for students). Which sectors might potentially lose out from such a transition? As many commented at the recent COP28 negotiations – ones that also did not go nearly far enough, how can we make the transition a socially just transition? i.e. avoiding the catastrophes that so many former heavy industrial cities faced in the 1980s? What can social and political history teach us?

These are just a few of the questions we need to be taking on – and urgently. I just don’t get that sense of urgency – and of the scale of the challenge facing us, in the report.

Hopefully this will be something that the public can pick up on and cross-examine the party candidates on in the run-up to the looming general election.

Food for thought?

If you are interested in the longer term future of Cambridge, and on what happens at the local democracy meetings where decisions are made, feel free to:

- Follow me on Twitter

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge.

One thought on “Ministers and water industry chiefs are in denial about the scale of our water crisis”