Turns out the opportunities the pamphlet issued by the Ministry of Education turned out to be far more than just the subjects – something today’s senior politicians might reflect on.

You can browse through the pamphlet here – it arrived earlier. The Minister for Education at the time was Ellen Wilkinson – the first woman to hold the post in UK political history. Tragically she died in the year this publication was issued by her department. She was only 55.

“What is the pamphlet about?”

More than just the subjects in a prospectus.

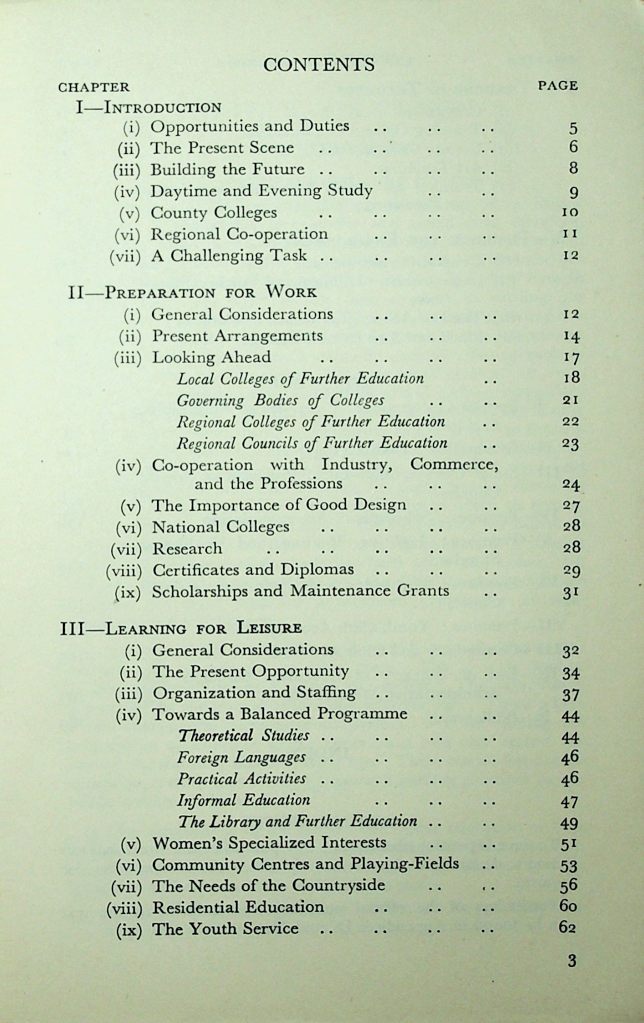

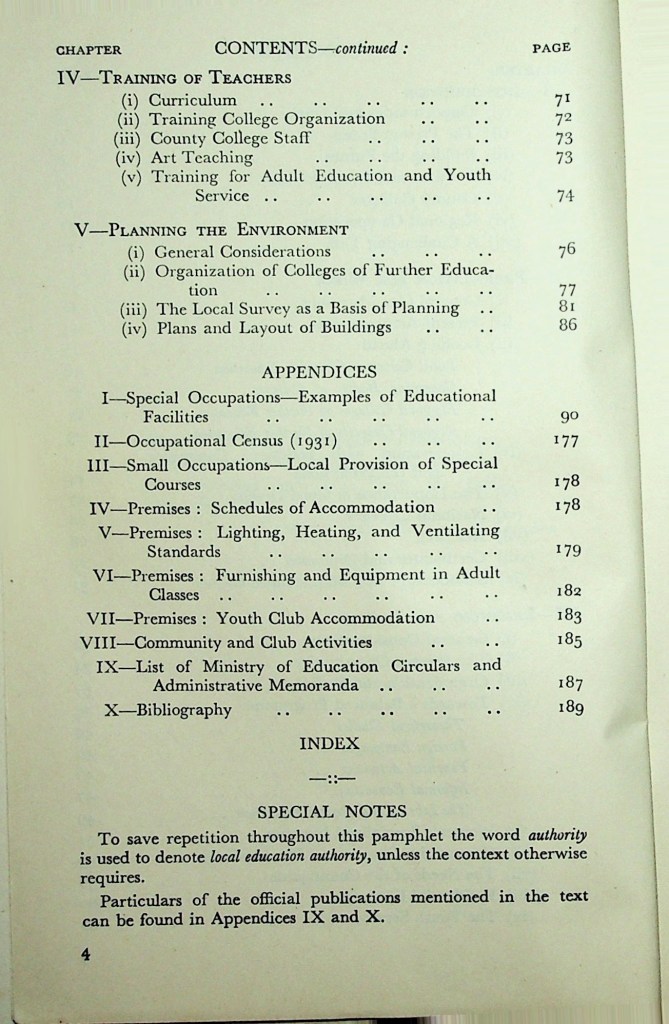

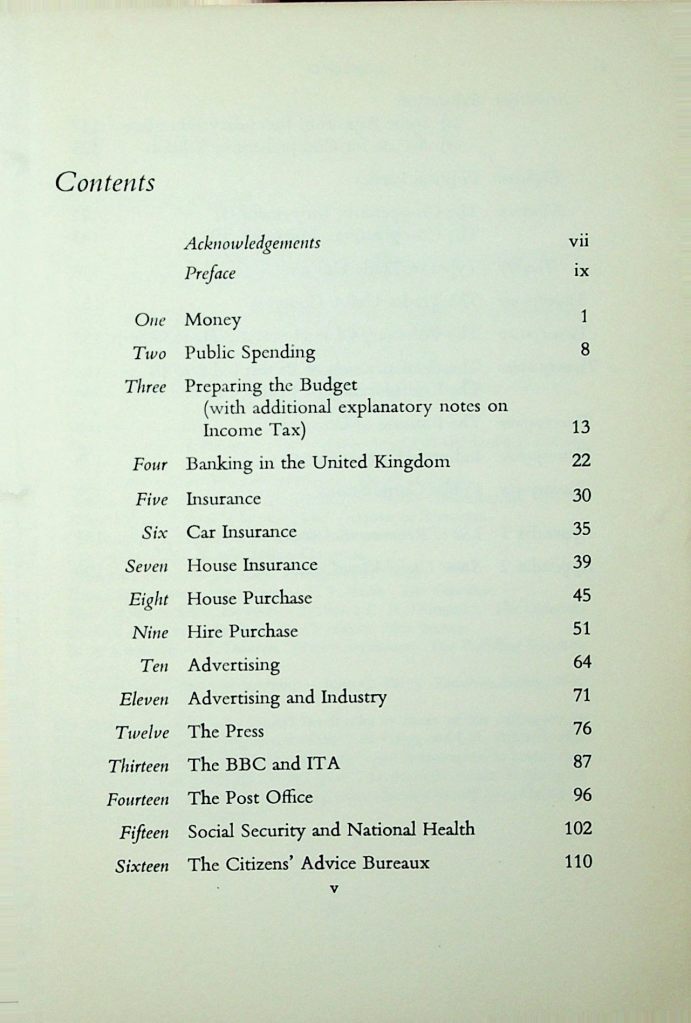

With such historical texts, often I find that the contents or the indexes give a hint as to whether the book is worth exploring further. In my case I’m more interested in how things are applied rather than the deep and heavy theoretical text behind the principles. When you have the attention-span of a kitten or a goldfish, concentrating on what can feel like dry academic tomes isn’t easy!

Mindful of the post-war reconstruction context *and* the massive expansion of the state under Clement Attlee’s Labour Government, the pamphlet covers far more than just the vocational educational policy area. It covers leisure, the training of those who will teach, and also about what further education colleges should look like as buildings and community facilities.

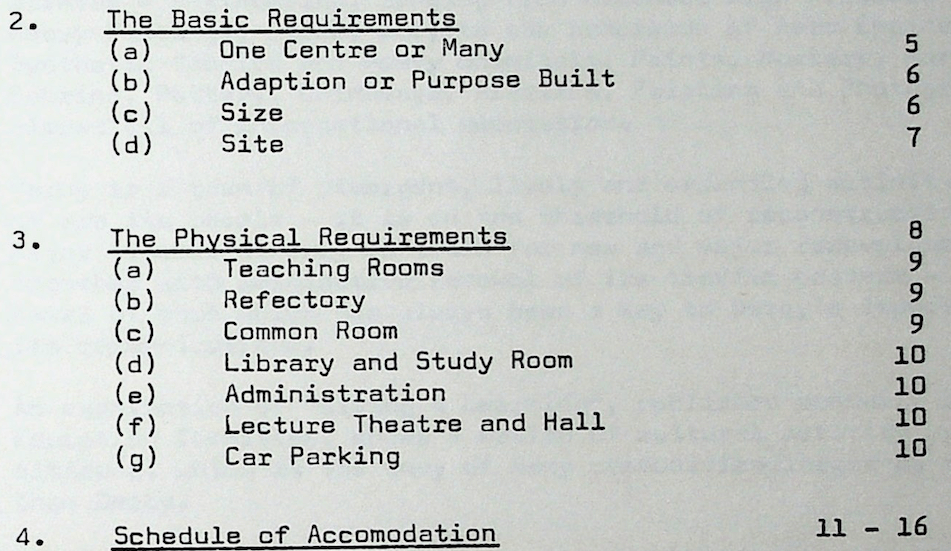

Above – Further Education (1947) pp3-4

“Why can’t we have stuff like this today?”

We can – if we really want to have it. Much depends on political priorities and given the remarks of one of Ellen Wilkinson’s successors, former Education Secretary Charles Clarke speaking in Cambridge in January 2024 at Anglia Ruskin University, we are at a point in history and politics where there is a big change happening. For those of us who lived through the 1990s, we can feel elements of that – even if the enthusiasm for Sir Keir Starmer isn’t anywhere near what was happening with Tony Blair back then.

What that does not mean is waiting for Labour to hand out ‘the goodies’ to a passive but grateful audience. Eglantyne Jebb warned us of that in Cambridge back in the early 1900s.

“I was a long time realising that the social reform on the part of the Conservatives is like charity in the hands of a Lady Bountiful – everything to be made nice and pleasant, but the ‘upper class’ is to be respected and obeyed. The corruption of elections first opened my eyes and I came to believe that no social reform could be of use that did not promote the independence of the people.”

Eglantyne Jebb – Cambridge Independent Press, 08 July 1910

At the time, Miss Jebb was campaigning across town for the Liberal candidate Stanley Buckmaster KC, who had lost the borough seat in the general election at the start of the year having won it in 1906 in the Liberal landslide. (He was to be unsuccessful in the second general election of 1910 – elections that also saw war poet and Liberal radical Rupert Brook driving about the place getting voters to the ballot boxes – crying out “I hate the upper classes!” in one letter saved by Sir Geoffrey Keynes, Florence’s younger son).

Preparation for work, and learning for leisure as side-by-side functions

One of my persistent criticisms of the current Political culture is how it treats skills policy as an isolated stand-alone thing to have money and policy resources thrown at it. In particular basic skills such as Maths and English, the mindset from ministers and politicians feels like that it is something the learners are taken out of all other contexts, and have the skills ‘hammered home’ into them until they pass the exams. At which point the boxes are ticked, and reported back to Parliament as ‘success’. The reality as many teachers in further education will tell you is that those basic skills need to be taught within wider contexts – ones that involve the choice and consent of the learners. That was one of the things I learnt when I did my basic teacher training over a decade ago at Cambridge Regional College – one of the successor institutions to the Cambridge Technical College which was so brilliantly developed by Dorothy Enright in the interwar era.

As with Ellen Wilkinson, Dorothy Enright died before her time. Yet her legacy 20 years later was a course catalogue that reflected both preparation for work and learning for leisure, as the prospectus for 1954/55 demonstrates. It was the change of government policy in the 1980s that led to the separation of the further and higher education functions of what became known as CCAT – the Cambridgeshire College for Arts and Technology – from which emerged Cambridge Regional College (CRC), and Anglia Polytechnic University (APU) in the early 1990s. In the mid 2000s, APU was renamed after John Ruskin (who only rocked up to make the opening speech of the original School of Art – Dr Sean Lang saying William Beamont has a much stronger claim – as does Ms Enright). Around the same time, CRC dropped its provision of academic courses to focus on vocational skills – again in response to changes in government policy.

The class divide is painful to look at – and it appears to have been designed in, however subconsciously

Much as we may like to think ‘Well this is how it has always been’, and that the idea of going to school, college, university and so on is the way things either are or should be in policy-making circles, history tells us something else.

Curriculum design, and availability of facilities and workshops really matters – as does learning cultures

In the mid-1990s I remember the ‘Life on a piece of paper’ mindset in South Cambridge – and being utterly brainwashed by it. The entire structure for those of us streamed into the top academic sets were that we were going to do well in our GCSEs, were going to go on and do well in our A-levels, then go onto university and beyond into well-paid jobs and middle-class-is-magical paradise. As wonderfully lampooned 15 years later by the BBC Mongrels puppets. (The ‘life on a piece of paper’ being: “Born, nursery, good school, great college, top university, graduate job, marry, have family, retire, die. Life lived”).

And the belief from the adults and the institutions around us at the time seemed total. After all, for the schools in particular their success measures involved exam results. Moreover, I seemed to do quite well in them. So why would I question it? Especially given that no one else in positions of authority seemed to be. Note the rhetoric from the then Social Security Secretary Peter Lilley in 1992 – one reflected daily by the tabloids. And there was no internet or any outlet to challenge such views. That mindset in a very different historical context for me was bluntly captured by former Royal Marine Ray Turley [trigger warning – racism] who part of the Anglo-French military operation to seize the Suez Canal Zone in 1956 by Prime Minister Anthony Eden. The concept of ‘those who got in our way, stopping us succeeding were nothing but trouble’ resonates strongly. Obviously instead of resorting to violence, my mindset at least was that getting high enough marks in my GCSEs would move me onto a new institution where my troubles would evaporate. (Haha! Yeah, right!) Accordingly, my response to those incentives was to knuckle down at the expense of anything to do with art, drama, music, and anything practical. Academia was the ‘way out’. Apparently.

That mindset was also prominent at college and university too – even though there were more facilities to take advantage of. But that required cultures that could break out of exam-driven mindsets – which was a tough ask for institutions that were also judged on the exam results of their students. It was only when I got to the public policy world in the civil service during my London days that the institutional flaws of the 1990s began to make sense. ‘Show me what you are measuring [policy-wise] and I’ll tell you what your priorities are’ said one seasoned policy adviser to me in the mid-2000s. It’s like what one of my former fellow students said halfway through our degree course: “If it’s not on the syllabus and not going to be in the exam, I’m not studying it. Why bother?”

The incentives of the institutions combined with my own hotwired, narrow mindset of the era stopped me from broadening my horizons in my formative years

It’s one of the reasons why I really like the principles of the EBacc – because it widens the interests that teenagers can cover, and is not dominated by academia. Tom Allen brilliantly lampoons school in the 1990s – in particular maths. But then look at the syllabus for technical colleges on the Citizenship pathway on the English and Social Studies option from 1966:

Above: On Citizenship – English and Social Studies (1966)

Can you see how useful incorporating English and Maths into the above subjects might have been even for 1990s teenagers? At the same time, there is a political context. In 1966 the then Labour Government was in the process of bringing in comprehensive schools and overhauling the education system. Fast forward to the early 1990s – there is no way the Conservative Government would have approved of a syllabus putting the trade unions in a good light. It was a highly politicised time. As education policy always is.

“What does the book say about what colleges should look like?”

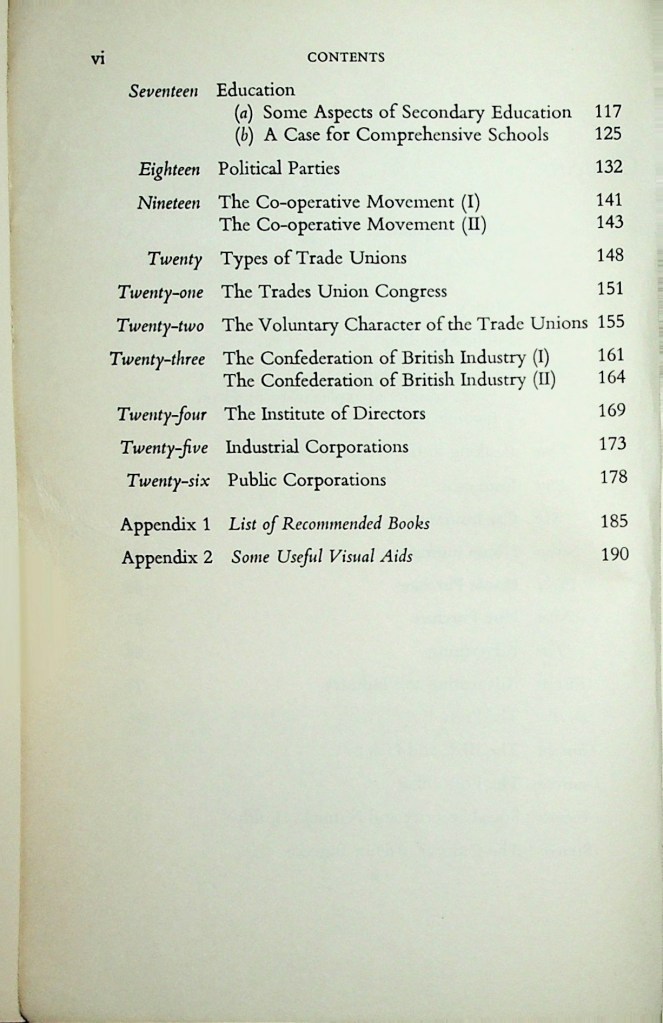

Again, context matters. The late 1940s were a time of huge labour and materials shortages. Therefore the guidance for small colleges comes as no surprise:

“The simplest arrangement for a small college is the rectangular building, the corridor on each floor having windows on one side and a row of rooms on the other.”

Further Education (1947) p87

We get a reminder on the following page:

“The achievements of the war years in housing the youth service have shown what can be done in difficult circumstances, and the same makeshift arrangements must be applied with equal determination to the needs of the adult community.”

The book also covers youth service provision beyond formal education.

On the page prior, it comments on facilities needed for adult education classes too – mindful of the need to get the maximum use out of limited facilities.

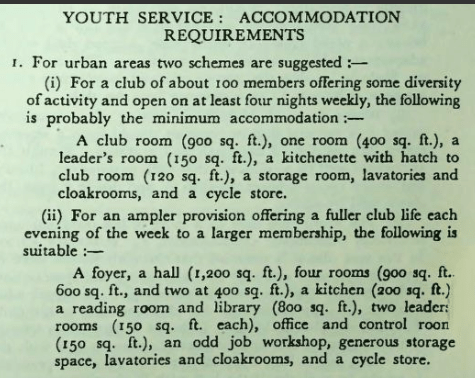

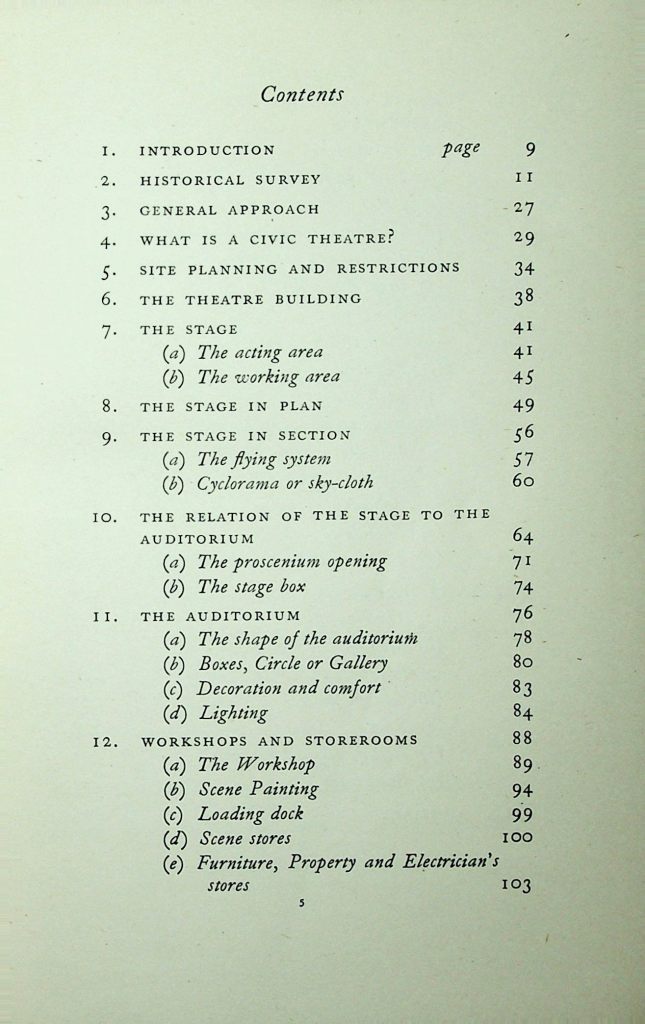

Fast forward to 1968 and Derby WEA provides an example of a bespoke adult education college design…

…in all its brutalist glory. But it’s worth having a browse, because it’s an example of how the people of the time assessed user needs in the context of the technologies and political/social/architectural cultures of the time.

Above – An ideal adult education college (1968) Derby WEA

Above – from the contents – note the basic requirements look at location, and the physical requirements look at the needs of service users (people!) and the demands of the courses that are to be taught there.

Some of you may want to compare that example with what former Oxford Don Sir Richard Livingstone wrote in 1944 on Citizen Centres for adult education. He was writing at a time when materials were in even shorter supply, but also at a time when the public was thinking about life after the war, and what sort of society they wanted to build. Maurice Alderton Pink’s book on Social Reconstruction from 1943 makes for interesting reading in a similar context.

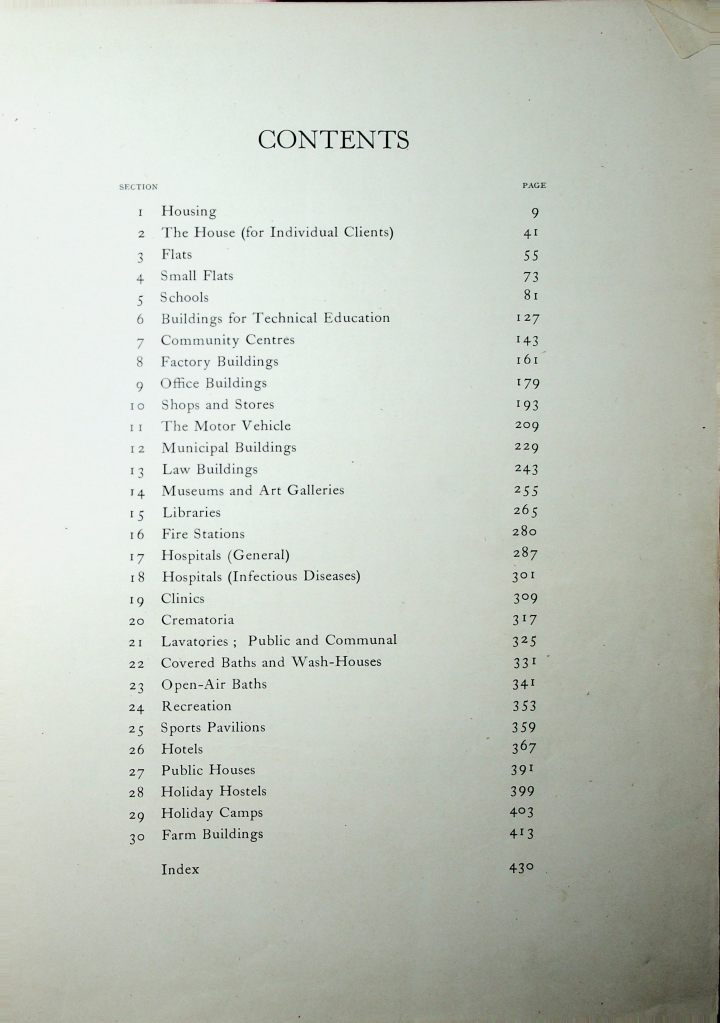

And finally…what the building and architectural establishment thought should be in our towns and cities.

The first edition was from 1936 but this edition is a post-war one from 1948 – from which the list below is taken from:

Above: Planning – The architect’s handbook (1948)

The only thing missing is the civic theatre! But the olden days has got that covered too!

Above – Richard Leacroft’s work from 1949 on Civic Theatre Design

This matters for Cambridgeshire people given the large housing developments being proposed. We *must* get the provision of facilities and amenities right, because previous generations of politicians, financiers, developers, and University bosses have failed our city. This generation must do better than to leave an ever-growing infrastructure gap that Dr Andy Williams, formerly of Astra Zeneca, identified and spoke out about last year.

Food for thought?

If you are interested in the longer term future of Cambridge, and on what happens at the local democracy meetings where decisions are made, feel free to:

- Follow me on Twitter

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge.