A new report from an unfortunately-named think-tank (due to a political party/limited company with the same name) provides a template to work with

Before I start, for those of you departing birdsite and heading over to BSky, I’m at the latter too.

Achieving ‘the devolution revolution’

The publication is part of a research stream by the Reform Research Trust that funds the think tank of the same name, which is titled Reimagining the Local State. Which in a nutshell is what I’ve been trying to do for the best part of a decade-and-a-half. Hence trying to bring them together into a series of themed lists here.

“Pictures please!”

Here you go.

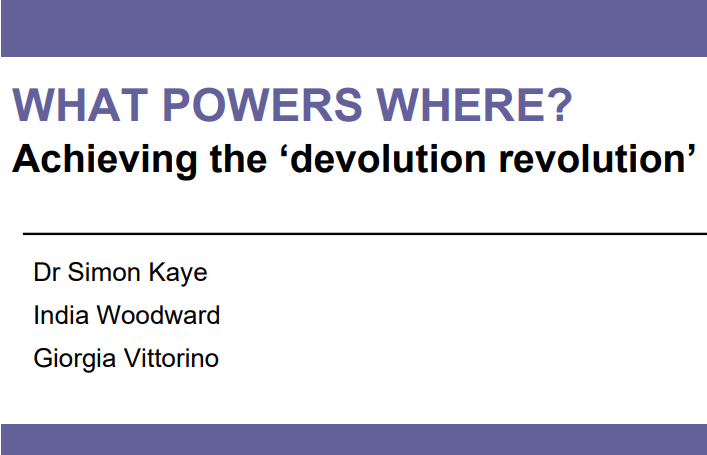

‘What should each tier do?’

To break down the above diagram:

Regional

At the moment it’s a bit of a mess. The Environment Agency regions (DeFRA) do not match the Department for Transport’s sub-regional transport bodies which themselves do not match the Combined Authority boundaries of the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. Don’t get me started on health (eg The East of England Ambulance Service) or education (Regional School Commissioners for the DfE) or Police & Crime Commissioners (Home Office!)

Local council tier

The academisation policy of Michael Gove really messed up the local tier, removing much of the local council link with schools. I remain to be convinced that, all other things being equal, the system of academies and multi-academy trusts is the difference between ‘successful educational outcomes for children and young people’ (to use the jargon). Furthermore, it makes it much harder for other local public service providers and community groups to know who to engage with – which means children miss out. What might be good for one sector is not so good for another. How do you reconcile the two? Hence having to think about each settlement in the round rather than in separate silos.

Hyperlocal/Neighbourhood

You can already see the problem with some of these issues. Private leisure centres are outside of scope (Cambridge is one of the most unequal cities in the country) while tourism is already beyond the ability of the existing lower-tier city council to manage properly.

Essentially the publication tries to answer some of the big issues that Lord Redcliffe-Maud and team tried to answer throughout the 1960s as they re-invented local government.

The city of Cambridge lacks both a serious regional tier and a hyper-local tier

The cities of Cambridge and Peterborough are not parished – we don’t have urban parish councils. The rural districts of Cambridgeshire however, are parished. For example you can see the list of parish councils in South Cambridgeshire here. Some parish councils have such small populations that the list of responsibilities they have are very small, while others such as the newtowns are on their way to becoming mini-district councils such as Cambourne Town Council. Others were once fully-fledged local councils before the Sir Edward Heath’s reforms of 1974 – such as the town councils of Huntingdon, St Neots, and Chatteris in other parts of Cambridgeshire – the reforms that saw the creation of a county council that was supposed to function like a mini-regional tier. Yet by squishing two economically and culturally separate sub-regional economies (Greater Peterborough, and Greater Cambridge for want of any other terms) together, we got the worst of both worlds.

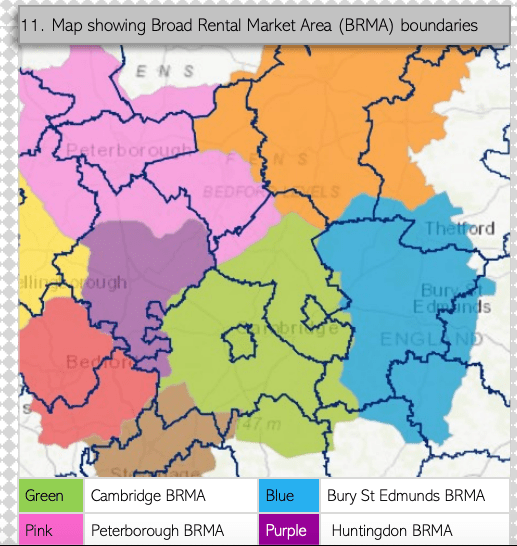

Above-Left – you can see how the rental markets indicate the spread of economic spheres of influence (via Cambridgeshire Insight Housing Market Bulletin Edition 60), and how this relates to current council boundaries. Above-right, the rejected proposals from Redcliffe-Maud 1966-69

It is those proposals from Redcliffe-Maud which would have made an ideal framework from which to build a light rail network within it – such as the proposals outlined by Cambridge Connect’s light rail strategy to the Combined Authority here.

I’m still of the view that the old Government Office Network for the Regions – formally created by Michael Heseltine in 1994 had something to offer in terms of a coherent structure. It struggled because the ministers responsible for it either lacked the gravitas within Cabinet, or the drive that comes from the belief in the structures and policies needed to align the rest of Whitehall to work within the same consistent structures. The result all too often was that ‘on the ground’ middle-to-senior civil servants retreated back into their departmental silos rather than acting as a single regional tier of government. Understandable if you’ve got one department responsible for targets to protect the environment while another department is responsible for a regional economic growth target – one that an environmentally damaging infrastructure proposal is a key component. The Civil Service Fast Stream trains you for/tests you on scenarios like this.

“Which tier should be responsible for what?”

As the report says, the UK – and England in particular – has sort of muddled through it, and the mess we have is the result. Not surprisingly, frustrated ministers (and advisers) can think of little more than competitive funding pots for councils to bid for that ministers decide to pick from.

For me, the first thing to look at are the functions, facilities, buildings, and services that people must have to survive, want to have, and would like to have for the settlements they live in. If you want to apply Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to the different types of public services, feel free.

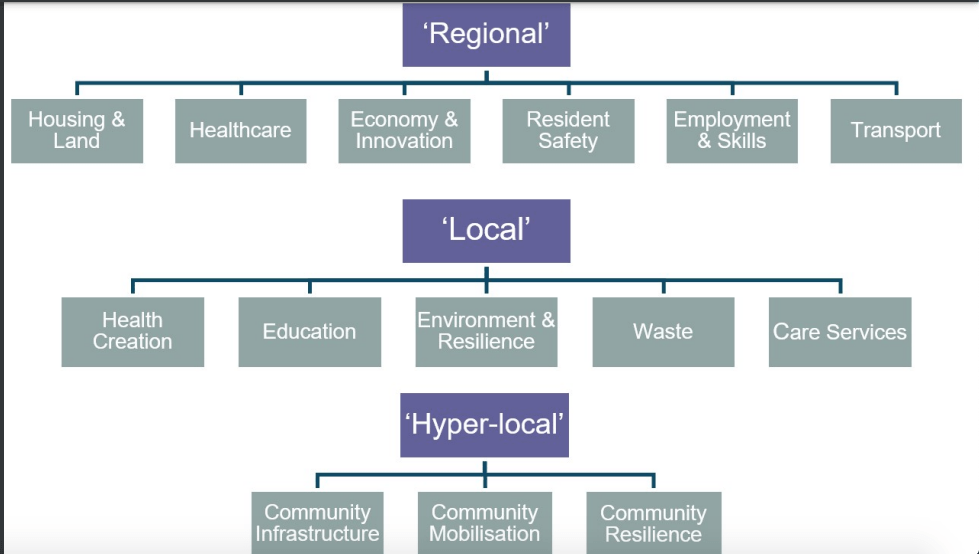

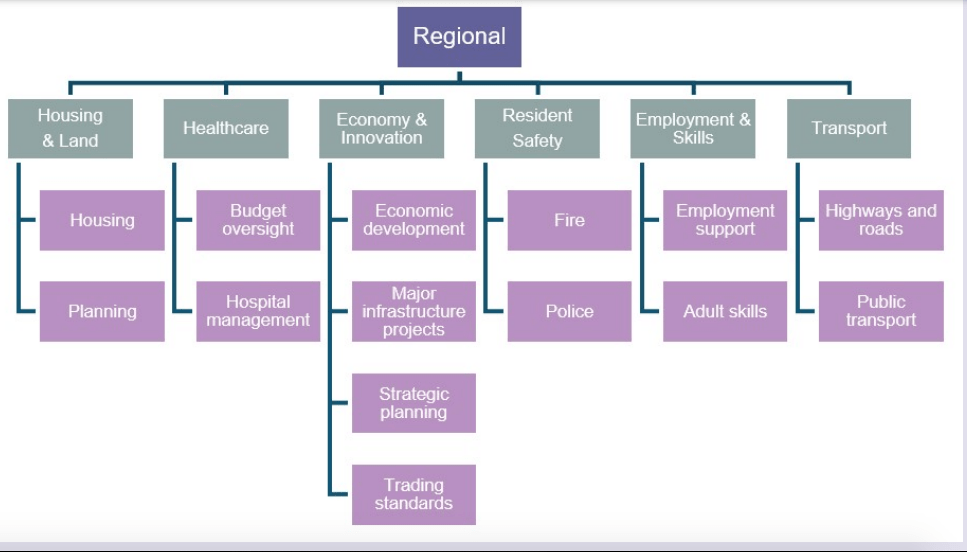

Above – detail of what types of services might be provided by which tiers: RRT (2024) p12

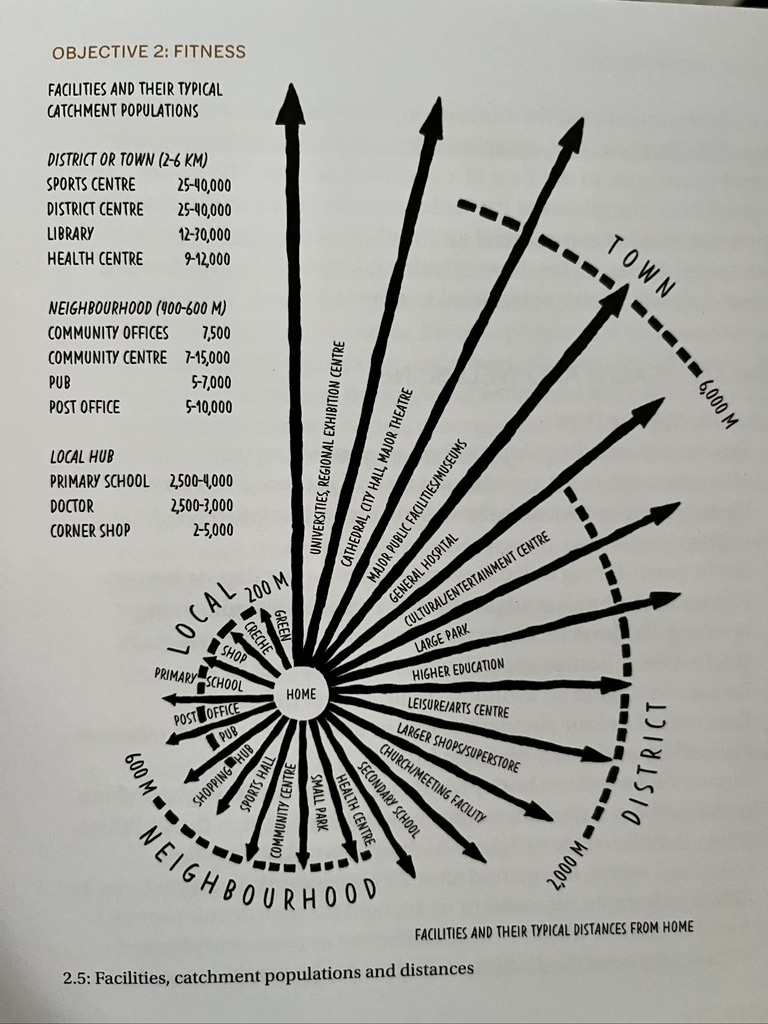

What makes this a little confusing is privatisation of the old public utilities. Water, gas, electricity, telephone services – all were privatised by the Conservatives in the late 20th Century. Yet we know that our cities would grind to a halt if those services ceased to exist. Hence a more broader take as illustrated by Rob Cowan below in his splendid book on Urban Design that looks at the services and facilities irrespective of provider is a more holistic take.

Above – Essential Urban Design by Cowan, R. (2021) RIBA

The one prominent item missing on Cowan’s diagram is anything about institutions of democratically-accountable decision-making. For example at a neighbourhood or district level you might expect to see a parish council. At a town/city level you’d expect to see a municipal council. For county towns and regional centres, you might expect to see a regional or county centre of governance. That said, ministers and political parties have moved such functions out of historic county towns for both party political purposes and for economic regeneration purposes. The principle being that firms will follow the seat of power. The reality however is that England remains highly centralised so the actual economic impact is hard to tell.

Applying the principles

The advantages of devolution:

- Context tailoring and join-up is the benefit that arises when local authorities are equipped to identify local assets, needs, and priorities, and specifically design their approach in a way that suits such contextual factors.

- Local accountability and partnership is the benefit that can emerge when devolution has enabled conditions where the users of services and communities themselves can have direct input about the quality of the governance that effects them, and contribute to much more rapid cycles of learning and iteration to help bring about improvements in the local state.

- Systemic coproduction is a benefit that can only be realised at sufficiently small scales of operation, where the local authority convenes and partners with local businesses, institutions, and communities themselves in order to deliver services and decisions that might involve markedly different behaviours from both citizens and the State.

Above – RRT (2024) p19

Two textbook examples include the strong link between poor housing standards and poor health indicators. The Whitehall silos through which funding is distributed means there’s a huge incentive for central government to allocate funding to those places where health indicators reveal higher-than-average levels of poor health. However, that money cannot be spent on housing. Yet the root cause of those high levels of poor health may be driven primarily by a large proportion of the local housing stock being of a very poor standard – combined with a local council too impoverished and under-powered/resourced to do anything about it.

A centralised system of siloed/ringfenced grants cannot solve that problem. Hence the move by the last Labour government to ‘remove the ringfences’ and make grants to councils based on things like poverty indicators in return for visible progress and improvement. Critics of this system (which I worked on in the mid-late 2000s) said it was still too ‘top down’ – and avoided the more difficult problem of overhauling and strengthening local government to so that voters and residents would be the ones holding councils to account, not Whitehall. But that meant having ministers competent and confident enough to accept councils might do things they don’t approve of, while at the same time not making party political capital out of things that might go wrong as a result.

‘Design principles for English localism’

The heading for Chapter 3.4 of the report

It reads like a list of buzzwords, but I’m going to try and apply each of these to what I call ‘Great Cambridge – i.e. Redcliffe-Maud’s vision of what a unitary council could have become – adding the strengthened parish and town councils that I wrote about in 2023 here

- Subsidiarity: “All other things being equal, powers should always be held at the lowest/smallest scale of organisation compatible with excellent outcomes.” Which was meant to be a core principle of the EU but half a century of hostile press combined with its own unforced errors means it’s easy to mistake ‘Eurocrats trying to straighten British bananas (grown not in Britain)’. That said, subsidiarity functioning properly would see an end to pet schemes from ministers acting like the Lady Bountiful – a figure that incurred the wrath of Eglantyne Jebb in early 1900s Cambridge.

- Sustainability – it goes without saying that you don’t want a system that will bankrupt the residents and businesses, nor end up too dependent in the long term on central government support. At the same time you want whatever structures are there to be able to make positive differences rather than to be seen by residents as an unresponsive tier of government – which was what the old GO-Network was often seen as.

- Regionalism – This for me is everything Rail Future East as a starting point on electrified public transport powered by renewables. This should cover the things that cross council and county boundaries For example East-West-Rail could and should be (in my view) a major transport project overseen by a consortium of three regions of the old GO-Network: South West, South East, and East. The previous Labour Government should have started work on it in the early 2000s but didn’t. At the same time the regional tier should also cover regional level facilities – mindful that for some leisure facilities, Cambridge already carries out that function because surrounding towns are far too poorly-provided for.

- Hyperlocalism – as at the top, the starting point is my 2023 blogpost here. i.e. ***paid full-time unitary councillors*** supported by part-time councillors functioning at town and parish level, which unitary councillors are also automatically members of. Where a settlement has a very strong case for forming its own parish or town council, powers and funding can and should be devolved – with the assumption on devolution first, and also with powers to escalate upwards if such a council cannot resolve an issue (or needs additional funding for it)

- Flexibility – No ‘one system fits all’. For example some areas may need to focus on getting the very basics right while others might have very specific barriers which, if overcome (such as the lack of a road or rail bridge at specific pinch points) could make a huge difference – but may need a disproportionately high spend for a short period of time to get it built before reaping the benefits. See also re-opening the Cambridge-Hunstanton railway, and the Cambridge-Great Yarmouth railway. At the same time, Cambridge would need the flexibility to ensure that the University of Cambridge and its member colleges were reined in – and required to account for the needs of the city when taking decisions on investment and expansion. Furthermore, some things that might be suitable for town-level governance would be too much for Cambridge to deal with alone – such as managing tourist numbers. (Something that would need co-ordinating with transport authorities if we get a light rail to tax the day-trippers and ban tourist coaches from the city limits).

- Specialisation – Not everything can or should be in Cambridge. So – in co-ordination with regionalism and excellent public/active transport networks, what facilities and industries could be located in nearby towns and counties? One easy example: Newmarket and horse-racing. Hunstanton for the seaside – Addenbrooke’s used to have a convalescent home there! What could the new large facilities be for Cambourne, Waterbeach, and Northstowe?

- Consistency – Cambridge should not be a ‘special case’ – not least because it adds to the confusion for residents. Which is what makes Redcliffe-Maud’s study of 1966-69 ever so important (click here and scroll 1/3 down to see the scanned docs & maps).

- Join-up – Easier said than done, but no one single policy or building project will solve everyone’s problems. For example if Cambridge is to build all these houses and sci-tech parks, it will need the utility firms to get their act together. Furthermore it will require significant investments in training up the local workforce far beyond what the cohort of young people are capable of meeting. In which case where are the policies to encourage adults to retrain? (And enable them to retrain if they have existing burdens (student debts, mortgages) and caring responsibilities? You can’t just assume they can spend a whole year not earning.

“What do they recommend specifically?”

- Bring back an improved version of regional plans. (We completed one in 2010 then Eric Pickles stamped all over it)

- Have a clear set of rules consistent across the country on powers & responsibilities for each tier.

- Devolve by default unless there are very clear reasons (based around an area not meeting specific criteria – think poor governance) for powers to be withheld. (The report cities an earlier publication by the same think tank)

- Have an effective but proportionate system of monitoring and evaluation – especially when it comes to assessing regional plans. That should also mean providing understandable reports and information to residents that are interested. For me this should be incorporated into any civics/citizenship education functions

“Could it work all together?”

It would require some radical thinking (which I tried here on a Great Cambridge Council and a Light Rail to service it) but it needs serious policy work on it. At the moment it doesn’t look like ministers are interested in major changes in the short term, but at some stage they will have to deal with a structure that, as the Commons Public Administration Committee said in 2022, is one that’s in need of a serious overhaul.

Food for thought?

If you are interested in the longer term future of Cambridge, and on what happens at the local democracy meetings where decisions are made, feel free to:

- Follow me on Twitter

- Like my Facebook page

- Consider a small donation to help fund my continued research and reporting on local democracy in and around Cambridge.

Below – one of the policies that was due to follow Strong and Prosperous Communities was Total Place – which I wrote about here – only it could be making a comeback.